Monsignor James P. Shea, priest of the Diocese of Bismarck and President of the University of Mary, spoke with Prime Matters on October 14, 2020, to discuss his vision for Catholic higher education and the importance of forming students' imaginative visions within that project.

Prime Matters: Monsignor, you have been wrestling with the questions and demands of running a Catholic university for more than ten years now. Based on that experience, what sorts of things need to be addressed or developed at a Catholic university, broadly speaking, if it is to maintain its reasonable identity as a Catholic institution?

Monsignor James P. Shea (MShea): From the beginning, I knew that the question of Catholic identity and a sort of continually deepening engagement with the Catholic intellectual tradition needed to be at the heart of university life. I also knew there were forces actively at work in the ethos of American higher education – and even American Catholic higher education – that would need to be addressed thoughtfully. With that awareness, it has been helpful to bear in mind Ex Corde Ecclesiae, which presents the interesting notion that a Catholic university is, in its essence, a Christian community. It’s not simply an administrative unit or a center for training, but rather it’s fundamentally a community of believers who share life together and are passing it on to others. That idea has guided much of our work at the University of Mary, and it has been important to be very intentional about constituting a community of like-minded and high-minded people along the way. Developing and maintaining a community comprised of men and women who are deeply immersed in the Catholic intellectual tradition, and who love that tradition and live out of it in their own lives rather than approaching it as something merely to be taught, has been crucial.

On a related note, I have found that one can never be too clear about articulating an institution’s mission and the implications of that mission. In other words, I think that a lot of places in our time have a tendency to present a sort of general vague statement of conviction that lacks staying power. Those vague statements are unable to satisfy the question of what a Catholic university ought to be doing. We have been very careful from the beginning to be clear about what our mission is at the University of Mary and how that mission engages with this moment of renewal for Catholic higher education.

Prime Matters: The idea that a Catholic university is, at its core, a Catholic community, raises the obvious question of the place of faith in the project of a university. You have indicated before that faith actually has a central role in the project of a university, rather than being something merely accidental that happens on campus. Where does faith fit into the project of higher education, and what are ways we sometimes see it being pushed to the margins?

MShea: Sometimes we seem to find a type of subconscious shame around questions of faith in the academy, which is a capitulation to an underlying sense that faith and reason do not really have much to do with each other – that religion and science do not intersect in any meaningful way. That mindset, although one of the fundamental dogmas of modernity, does not have any place as a founding principle of a Catholic university. One of the efforts we have been particularly focused on at the University of Mary over the course of these years has been recovering a sense of how the Catholic faith is not enervating, but rather is enlivening in terms of the adventure of the intellectual life.

There are instances in which the Catholic imaginative vision will find itself in a sort of battle with the prevailing modern secular vision, which often actively undermines the place of faith in higher education. Critical theory in the liberal arts and the humanities comes to mind as one such theory that the Catholic vision will inevitably have to tussle with, and it is important to allow the potency of faith to show up in the midst of those conversations.

So much of contemporary higher education – and this is certainly true at the University of Mary – is focused upon the professions. When such a professional focus is not balanced within the broader project of Catholic higher education, it can lead to the sort of divided, fragmented life so many people experience today as a result of the deepest questions and concerns of human existence being entirely cordoned off. I think back to the opening pages of E. F. Schumacher’s A Guide for the Perplexed, in which he recounts a memory of standing in Leningrad, hopelessly lost, seeing several large churches that he could not locate on the map. A local offered assistance, saying that in Leningrad, they did not mark churches on their maps. When Schumacher noted that several churches could be found on the map, the local replied, those are not living churches, those are just museums – it is the living churches that we do not put on our maps. Schumacher recounts that in that very moment, the failings of his own education became clear to him: he realized that all kinds of prominent things necessary to navigate human life had been intentionally stripped away and omitted in the education he had received. I think a similar thing can happen in the professional fields, and that is why we have been so focused on bioethics in healthcare at the University of Mary, as one example. Healthcare education has always been a preoccupation for us, and it is one of the reasons the University of Mary was originally founded, so we sensed that engaging all of our health sciences students with a vivid sense of the great questions of bioethics is vitally important in our time, and we draw upon the impressive intellectual legacy of the Catholic faith for this.

I think what we have had to do, sometimes subtly and sometimes quite obviously, is to push back against this idea that there is anything for us to be ashamed about – either subconsciously or consciously – in engaging the deepest questions of the academy with the Catholic faith.

Prime Matters: It seems that the tendency has been to place the faith outside of the central intellectual project of the university, placing it in other aspects of student life and experience. Does the recognition that the faith actually has a central role to play in the core mission of higher education then change how we understand it to relate to those other aspects of student life and experience?

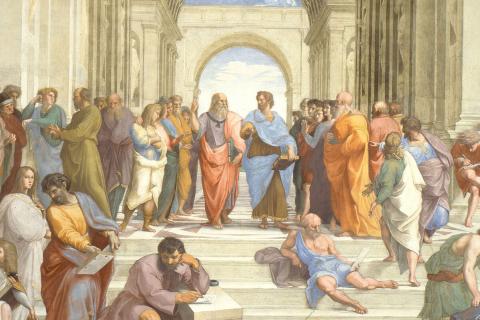

MShea: The genius of the Christian intellectual life is that it does not confine itself simply to what can be found in the Gospels explicitly, but rather looks to the great synthesis of the Christian ideal with the Greek ideal of education, which they called ‘paideia.’ The Greeks were asking broad questions, like “what is the ideal citizen of the polis morally, physically, intellectually, spiritually,” and so on. The commingling of that Greek ideal and the Christian ideal allows us to ask questions straight from the great tradition concerning something as seemingly extraneous as athletics, taking principles of virtue that can be found in Aristotle, for instance. This great tradition gives us first principles that allow us to engage all aspects of life through the lens of the Catholic imaginative vision, from the liberal arts and humanities, to the social lives of students, to the behavioral sciences, business, healthcare, and education, and even down to questions of policy and compliance.

The Christian tradition’s focus on fundamental first principles that can be ramified in almost any direction means that there is really no aspect of student experience that falls outside its scope. This all means that at a Catholic university, we do not confine our operations to ensuring that things like curricula and residence halls function, but that they function according to Catholic first principles.

Prime Matters: You spoke of the mission of a Catholic university in terms of an imaginative vision: could you say more concerning why you use that phrasing, rather than simply saying “Catholic doctrine” or something similar?

MShea: A key moment for me as regards the Catholic imaginative vision was when we started to do faculty formation seminars at the University of Mary, and Dr. Don Briel would help me to spell out for faculty the vision behind Catholic higher education. Many of our faculty would enter into these four-day retreats with a bit of trepidation, feeling quite intimidated by the prospect of such an extended discussion about Catholicism and how it interacts with their work as professors. After a day or two, however, a palpable astonishment would settle over the room, the result of the awakening of a Catholic imaginative vision. People would begin to realize that we were not talking about some narrow, parochial caricature of belief, which is what they might have expected due to their own backgrounds, whether arising from their formal practice of faith or from reading newspapers or from the broader cultural narrative. What they came to realize was that they were locating their professional lives within the context of a broad, capacious tradition. This tradition was interested in every question, and no area of inquiry was considered out of bounds, and it cast light upon all kinds of human concerns and desires. This, for many of them, was a revelation.

For me, that revelation – that awakening of an imaginative vision – is something we want to embed in the very ethos of the university. Such an astonishment of mind is meant to break over all the students and faculty of this community … for everyone, but especially for those who are committed Christians. When we come to see how each academic discipline brings a richness to human inquiry, and furthermore that these disciplines do not stand on their own and are not divided from each other but rather relate to each other in a particular way, we cannot help but step back and be astonished by the resonance. It all leads to this sense that there is some grand conspiracy afoot, that there is some mystery that runs beneath all things and brings them together. And then all of a sudden, it’s impossible to be bored anymore, or to squander our attention on trivialities, because we have found something substantial that we can really sink our teeth into.

When we talk about the Catholic imaginative vision as it relates to the project of higher education, then, we are not referring to something make-believe, but instead, to the astonishing capacity that human beings have to capture the whole world in their minds and to hold it there, experiences both past and present, things they know to be the case and things they believe to be true. From this standpoint, then, each person is able to engage the world with a deep sense of meaning and purpose and of a mystery that runs beneath all things and holds every field of human inquiry together. To say “Catholic imaginative vision” rather than “Catholic doctrine” is an attempt to indicate this broad vision of all aspects of human life.

Prime Matters: This reminds me of two lines from G.K. Chesterton. In the first, he said that the Church is larger than the whole world – it is not just a slice of the world but is actually larger than the world. It draws the world into itself and the world expands as a result. In the second, he said that the Church is the true home of everything truly human. This all lines up with the idea that the Catholic vision is interested in everything, because at the heart of everything is God-made-human in the Incarnation.

MShea: Right. The Catholic imaginative vision is not an area of inquiry on its own, because it is actually the whole picture. It is a view of the whole thing.

We can make a distinction here. At the end of “Key Aspects of the Catholic Studies Program,” the white paper about the purpose of Catholic Studies at the University of Mary, it is noted that the Catholic Studies professor, and by extension everyone involved with the project of a Catholic university, is not just meant to be a scholarly polymath. The idea is not to have some sort of encyclopedic vision of things, to be simply the sort of person who could win at Jeopardy every time forever. Instead, the idea is that the Catholic Studies project is not interested in every thing so much as it is interested in everything, the whole. We presented the same idea in greater detail in From Christendom to Apostolic Mission: “Christians don’t see some things differently than others: they see everything differently in the light of the extraordinary drama they have come to understand” (p. 74). The Catholic Studies project is not necessarily devoured by interest in dozens of fields, but rather is interested in how everything holds together. The highly specialized training many members of university faculty have received has not quenched the deeper thirst for relating that specialization to the whole of what is known.

That interest in everything – in keeping the whole of reality in view – is what makes the Catholic imaginative vision and the Catholic Studies project integrating. Underlying the mission of the Catholic university is the conviction that the whole of student life and education and training can be approached and arranged through the lens of the Catholic imaginative vision. It certainly takes dedicated, educated effort to pull it off, but the great tradition provides the necessary ballast for that effort.

Vocation and the Purpose of Our Lives

Archbishop Charles J. Chaput

Each human life is unique and unrepeatable, possessing a meaning and vocation meant only for you: a vocation is a calling from God with our name on it.

Prime Matters: This idea of the Catholic imaginative vision playing an integrative role at the university echoes John Henry Newman’s assertion that the highest act of the intellect is not the learning of specific facts or processes, but rather is the integrative act. Is it fair to say that training students into the art of seeing things integrally is the primary mission of university education?

MShea: It is vital that university education train students in the art of thinking integrally and seeing how to wrestle with questions such that they cohere into a larger vision of the world. Cardinal Francis George once gave lectures at Georgetown and Duquesne in which he noted that modern universities were collapsing into “high-class trade schools.” Importantly, he did not mean this to be some sort of blunt insult. There is something very impressive about training a human being for a specific task or profession, but that simply does not exhaust the task of the university; in fact, if a university does not do more than provide such training, it is not living up to its mission. In regard to such a task, Cardinal George added, there is “nothing remotely as universal” as the Catholic intellectual tradition.

Prime Matters: To shift gears for a moment: the generation currently inhabiting university classrooms and campuses has been raised quite differently than almost any previous generation, due simply to the reality of screens. What sorts of possibilities and struggles you have seen in your work with these students? In other words, given the task of the university, how do we apply it to our students?

MShea: I think there is a more serious-minded approach to life and to university studies among the last handful of freshmen classes that we have seen, and while they have a strong dependence on screens and social media, they are aware of that dependence in a way that our “millennial” students did not seem to be. So while our newer students are not any less addicted to their smartphones, they are at least aware of it and are concerned about it in a way previous cohorts were not. At the same time, we have seen a troubling spike in mental health issues, especially depression and anxiety. In other words, we are seeing that the promise of the technical revolution we saw bubbling up in the 1990s and then sweeping into the early 2000s has now met with a widespread disillusionment about its promises.

For many, the current pandemic has shattered the illusion that life is supposed to and most likely will go along well – that one is supposed to live a relatively settled, pleasant, straightforward life with occasional interesting trips and fun friends, limited challenges, and plates of food to post to Instagram. That sort of shallow triviality is no longer credible. People have come rapidly to recognize that life has its fair share of serious sacrifices and disappointments, and that common life – on a university campus, for instance – requires a kind of common purpose and shared sacrifice that we can rally around. This recognition that there is something deeper to life than trivialities calls people to stand for something, and hopefully such conviction could eventually rise to the level of being willing to die for something. Until you are willing to die for something, life is not worth living.

Richard John Neuhaus once said, “Spare me a gospel of easy love that makes my life a thing without consequence.” The trivial, consequence-free, mediocre vision offered by modernity that so many have grown disillusioned with has been shattered. There is something hopeful about this, but there is also something dangerous with such a deep, persistent disillusionment. If it is not met with a kind of formation that is adequate to respond to it and offer a deeper, more life-giving vision, it will result in an entire generation spilling out into the streets with maddening clamor. In other words, while we have a new opportunity to offer something substantial, this is also a powder keg if we fail to provide for it correctly.

It is really a profound opportunity, because what we have to offer in the Catholic tradition is the possibility of an epic life, a life that makes sense from top to bottom, a life in which no question is out of bounds because the answer can be sought with a kind of confident hope. Truth can always be found, although often with difficulty, and sometimes not completely. But the very seeking of it brings a wholesome joy to life.

Wordsworth once wrote, “Buying and selling we lay waste our powers, we’ve given our hearts away.” That’s the great cry of this rising generation, that’s how they experience life. So if we can respond with, “Wait, here’s something you can sink your heart into,” they’ll respond to it. Christianity has this great adventure on offer, and nobody else is stepping forward to present anything more compelling.

Prime Matters: When you look at our present moment – and particularly the Catholic Church in this moment – what sorts of things come to mind when you think of how universities can prepare their students to meet this moment? Where does the Catholic university project fit into the picture of our wider culture?

MShea: The Church has found itself in a kind of persistent onslaught. Over these past decades, there have been numerous instances of the weaknesses, the mediocrity, and the wickedness that are part of the Church being laid bare, revealing the profound battle taking place inside the Church. And so the great temptation here is to take that a step further and say, “This institution is not in any way a force of good in the world. Nothing good comes from what the Catholic faith has to say or offer.” You can see that in every aspect of culture, this constant onslaught and attempt both to attack the Church as the most pernicious thing while also to ignore it as the most trivial thing. Of course, the idea that it is so utterly pernicious and trivial don’t go together, but we see that dual approach happening constantly.

At the University of Mary, first of all, we find ourselves striving to be a place where serious young Catholics can come and engage in the great tradition and internalize the beauty of this great imaginative vision that has been the source of so much good in the world. I’m not just talking about Gothic cathedrals, but the whole tradition of human rights and different structures of government and law and beautiful art and music – all of these things. In addition to all that, we’re the kind of place where all sorts of people who have never encountered the tradition also come for various reasons, and our work with them is to awaken within them that same sense of wonder. Thus, we’re shaping and forming a coherent community which is able to provide impressive witness – the sort of impressive witness that is one of the key marks of apostolic life. Impressive witness should show up in a very palpable way in an institution like a Catholic university.

The Synthetic Impulse in Catholic Life

Bishop Daniel E. Flores

St. Hildegard demonstrates the synthetic impulse of the Christian vision, which recognizes that all of Creation is connected and that a mystery runs beneath all things, holding them together.

Because of our institutional engagement not only with the humanities, but also with the professions, we have been able to have a profound impact in the businesses and schools and clinics and hospitals that our graduates enter into in fulfillment of their vocations. We want a weary world to meet our graduates and say, “They have a brightness within them. I don’t know what it is, but my life is pretty unhappy, and these people have a brightness within them.” That brightness comes from the illumination of truth. It is the light that comes from true education. It is the result of human beings looking for the divine and seeking after those things that are perennially true and beautiful and good.

Prime Matters: Maybe we could give the last word here to something you touch on so frequently in your homilies and engagement on campus, which is the role of Jesus in all this. When one looks at all these things – be it the intellectual life and pursuit of truth, or the culture and all its various expressions, or dealing with particular moral problems – these things all end up focusing on the person of Jesus Christ as the beating heart of this imaginative vision. It’s obviously a big question, but could you give a glimpse of where you see the person of Christ fitting into the university as a community?

MShea: That is a big question, but I can give a few summarizing points here. This question would perhaps warrant an interview of its own.

First, we had talked earlier about this sense of astonishment that sometimes comes in the course of education, when a student glimpses that there is a mystery running beneath all things. That is the Word – that is Christ. Jesus himself is that mystery – that Word, that Logos – that stands at the heart of all learning and all human inquiry, illuminating every mind and every heart. So that sense of astonishment is not just the discovery of some type of coherent sensation, or a wholeness, but it’s really the discovery of a person. As you said, the person of Jesus Christ is the beating heart of this imaginative vision, which makes the Christian vision of the world unlike any other imaginative vision.

Second, Jesus himself, in the clarity of his teaching, as well as the animation of his life – that is, both through the words he says and the example he gives – provides the template whereby the great promise of intellectual inquiry can be properly located and can be most fruitful. Because of the fallen state of the people engaged in the pursuit of these highest things, we can easily be thrown off kilter and fall into error by pride. We tend to forget our humble nature – which is that we are a handful of dust held together by water – and we forget that we’re not pursuing these great things on our own steam. We’re actually pursuing these highest things of the mind in obedience to a call – a call given us in love by the One who created us, who has granted us the immense and unlooked-for dignity of being able to pursue truth and draw near to Jesus, who through the Incarnation assumed our nature as his own. Without the Lord, it would be impossible for us to pursue truth with humility and a proper sense of our own limitations.

The last thing I will say in this respect – and this certainly doesn’t exhaust the answer to your question – is that the path of discipleship is very distinct from the categories of excellence that are given to us by the world. This is true for university administrators and professors, in those roles as well as our vocational roles of priest, spouse and parent, or consecrated religious. There can be a real temptation to make even a Catholic university into an Enlightenment project in which you begin to set up systems for the perfectibility of human action in a modern lens, shot through with pride. One needs to set standards to foster excellence in human action to a certain extent – I’m thinking here about job descriptions and budgets and so on – but none of that is ever adequate for the real task in which God is working behind the scenes. While it is not always evident what he is doing, if you’re not obedient to his will day-to-day, you’re merely enacting a strategic plan that a group of “experts” consulted on and nothing more. Such an approach can easily turn a university into a center of ideology – and by ‘ideology’ I mean a set of ideas that is incommensurate with the human person, which doesn’t work humanly and thus has to be imposed in some ham-fisted way. The same shift happens in other contexts, as well, and it is the result of letting your discipleship corporately slip, and the thought becomes, “Oh, it’s all just about mental hygiene, and student outcomes, and return on investment, and endowment performance.” The whole human enterprise that is meant to be brought together and integrated in the university thus becomes disintegrated due to an exclusive focus on temporal concerns resulting in an exclusion of an overall spiritual vision. The stakes are too high for such a reduction!

Without the person of Christ at the center of everything at the university, a Catholic university becomes an Enlightenment project with a Catholic veneer – it’s easy to do, and it’s very dangerous. All this leads to the idea that the spiritual vision of the university cannot simply be a theory about God, but has to be of God himself, Jesus active in the life of the place.

Faith and Reason at the University

Foundations, The Catholic Intellectual Tradition

When faith and reason are properly understood, it becomes clear not only that do they not contradict, but also that faith has a central role to play in the project of higher education.