What does it mean to be a Catholic school? It is perhaps both a blessing and a curse that in the United States, Catholic schools have earned a general reputation for offering high-quality education. This is a blessing insofar as it speaks to the dedicated service of generations of educators and the sacrifices of countless parents; it is a curse insofar as it has led many to assume that Catholic education is differentiated not by any intellectual commitments, but rather by merely devotional or moral commitments. Prayer before class, scattered statues and Bible verses, occasional Mass, and the inescapability of theology class are the cost of accessing high-quality but otherwise normal academic and human formation. They are a backdrop; a quirk; a collection of isolated moments; an attempt at edification before the real work begins.

This vision of Catholic education implicitly takes for granted the notion that Catholicism is primarily a set of moral values and devotional practices. In reality, Catholicism forms an entire vision of the cosmos, asserting the purpose and unity underlying all Creation, the existence of a provident God, and the meaning of human existence and dignity of the human person. From these convictions arise moral values and devotional practices; without this holistic vision of the world, those values and practices lack context and appear arbitrary. The essential core of Catholic education - the element that makes it decidedly Catholic - is an intellectual difference rather than merely a devotional difference.

Within the Catholic vision of the world, human life itself takes on new meaning: we are not merely limited, but created; we require not only preparation for work, but also preparation for life; this present life is not important because it is all there is, but it is important precisely because it is a preparation for the next. Thus, mathematics becomes important not just for its salary and standardized test boosting potential, but because it teaches students the virtues of endurance and commitment; literature becomes important not just because "reading is good" in a vague sense, but because it forms our imaginations and helps us to live in the midst of invisible realities; theology becomes important not just because it fulfills a generic pious impulse, but because it introduces students to the true horizon and context of human existence.

When a Catholic school bases its identity in the unique (and demanding) intellectual project of forming students in the Catholic vision of the world, moral formation and devotional practice will follow naturally. But it is precisely the fundamental commitment to the Catholic intellectual project that renders a school "Catholic."

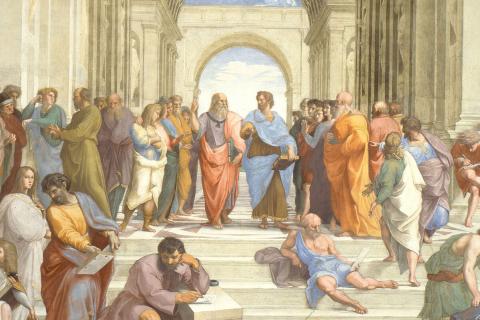

Faith and Reason at the University

When faith and reason are properly understood, it becomes clear not only that do they not contradict, but also that faith has a central role to play in the project of higher education.

The Vision of a University

Msgr. James P. Shea discussed his vision for Catholic higher education and the importance of forming students' imaginative visions within that project.