Educating Tomorrow's Leaders

Dr. Rod Jonas Dean, Liffrig Family School of Education and Behavioral Sciences, University of Mary

Dr. Paul Carrese, founding director of the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership (SCETL) at Arizona State University, sat down with Dr. Rod Jonas, dean of the Liffrig Family School of Education and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Mary, to discuss the crucial role of civic and liberal education in the life of a free society and the formation of students.

Dr. Rod Jonas (RJ): You’re the founding director of a unique program at Arizona State University, the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership (SCETL). To start, maybe you could say a bit about the work you’re doing at ASU and how this program came about?

Dr. Paul Carrese (PC): I’ll start with the project of SCETL, and then I’ll suggest a little about why I believe I was selected to be the founding department head.

But before that, I’ll say “thank you” to the University of Mary for hosting these sorts of conversations and inviting me to join. There’s quite a lot of harmony between SCETL and Mary College at ASU.

In 2016, the Arizona state legislature and the governor decided that there should be an intervention from the state government into the largest public university in the state, which is Arizona State University. They wanted to address what they thought was a deficiency and a lack of space in the university curriculum and in campus life for teaching, learning, and debating civic thought and leadership, and they folded economic thought into that. Part of their concern arose from an intellectual diversity initiative: the concern was that there was not adequate space for conservative or traditional thought. They wanted to address that concern in a spirit of debate and discourse rather than in a spirit of indoctrinating students in a particular point of view.

Their discussions culminated in a piece of legislation that proposed the creation of a new school at Arizona State University with a very long title, the “School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership.” For context, at ASU the term “school” refers to an academic unit of any size that is interdisciplinary. This school has been built over the past five years, and our faculty is a collection of scholars from a variety of backgrounds: political science, history, economics, American studies, and law.

So this mission was given to ASU, and the president and provost of the university and dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences put together a national advisory board. Some of the members of that board knew of me. I was teaching at the U.S. Air Force Academy at the time, where I had developed a classical great books honors program, which was a blended liberal arts and leadership honors program. They thought I would be interested in tackling the project of building a department with a similar mission – in this case combining liberal arts study with civic education and leadership education – from scratch.

Just months before I was contacted by ASU, I had been a finalist to be the dean of Arts and Sciences at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. I was disappointed not to have gotten that position, but the Lord works in mysterious ways. I think that experience made me open to the idea of taking on a new challenge and made my wife and our family open to moving. So when the opportunity to come to Arizona to start this department from scratch arose, I took it. It’s been a terrific adventure with some complications and challenges in the past five years.

RJ: As I’ve learned more about your program, I’ve found that your activity spreads far beyond the classroom. I came across a debate you hosted and moderated between Drs. Angela Dillard and Peter Myers, which included an open forum question-and-answer section at the end. I was very intrigued by the conversation, but even more so by the question of how moderated debates like that are received by the student body and the public. Are you finding that students are interested in engaging in reasoned disagreements in a debate format, especially when it concerns hot button issues?

PC: The first generation of faculty of this school has had the opportunity to take the name of the school and make something of it. From the very beginning, the president, provost, and dean all agreed with the proposition that given the words civic and leadership in the name of our school, we ought to be a very civic-minded academic department providing opportunities for broader learning to the entire ASU community, the larger Arizona community, and even nationally. So the public speakers program and debates we organize have turned out to be a very important part of our mission, and we’ve received special funding to invite national-caliber speakers under what we have called the Civic Discourse Project.

We are living in a very polarized moment in American history – not only in our national politics but also on university campuses. Certain topics can’t be discussed and certain speakers can’t be invited. We’ve faced that reality head-on and agreed that at a university there ought to be reasonable debate and discourse. So there are some parameters in place: we are hosting reasonable debate and discourse about the most important topics of education and American civic and political life.

In addition to hosting a series of speakers under a yearly theme, we have two dedicated topics every year: we host a Constitution Day lecture every September and Martin Luther King Jr. Day event every January. The debate between Drs. Dillard and Myers that you mentioned was for our Martin Luther King Jr. Day event in 2020 and focused on the 1619 Project that was just coming out of The New York Times, which was yet another heightened debate about the meaning of America’s founding, ideals, and principles in relation to racial justice and questions of civil rights.

Dr. Rod Jonas

The liberal arts help students develop a love of learning, an appreciation for the human mind and spirit, and the ability to discern what is true – all of which are ideal qualities in a preservice teacher.

Whenever we invite speakers and arrange debates, we make sure that the speakers are willing to engage in a candid, reasonable exchange of views. This sort of civil disagreement marked by civic virtue is what universities and broader public civic life in America should be about. Reasonable people understand that free people are going to disagree about all kinds of things, but we have a civic and intellectual duty to listen to each other and respond reasonably.

Our speakers know that after they speak they will be exposed to my questions as the moderator and then to questions from the audience. Keep in mind that these events are hosted at a large public university in the large urban setting of Phoenix and Tempe, so the speakers could be exposed to any range of questions and challenges from the audience. Our speakers also know that if they have been invited to share the stage with another speaker, they’ve been chosen because they disagree on the topic. We want to address specific topics and disagreements, but we’re also trying to address the larger need for civic discourse and civil disagreement.

RJ: I would be interested to hear how you use “reasonable discourse” as a parameter. Because while I agree with you, I wonder how to navigate it practically. Couldn’t “reasonable” be defined quite subjectively? And that leads to another question: how do you ensure that you’re not just bringing in people who disagree, but who disagree in such a way that a meaningful conversation arises?

PC: When I say that we use “reasonable discourse” as a parameter for choosing speakers, I mean that we’re not interested in inviting provocateurs or polemicists. We’re not interested in bringing in performers who agitate and rile up the crowd: Americans are quite well riled up at this point on a whole bunch of issues already! A core part of our academic mission involves trying to emphasize reasonable discourse and civil disagreement: that is needed both on university campuses and in American political and civic thought.

But you’re right, all of that can sound a bit subjective. One of the efforts we made from the very beginning was to find partners within ASU who would share the work of defining who our speakers and what our themes should be. We reached out in particular to the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication to find partners within the university who were interested in the broad project of promoting civic discourse. As you can imagine, the law school faculty were interested in freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and related principles, while the journalism faculty were interested in public discourse and a more reasonable discussion of views on public topics. So we formed an intellectually balanced advisory board for the Civic Discourse Project. I’m intellectually conservative, as are most of the faculty in our school, but we have a range of views on that advisory board that helps us to come up with reasonable parameters for topics and speakers. We’ve had a lot of success in finding partners within the university with a whole range of views, and we’ve formed an audience within the university community and the larger Phoenix area who may not always agree with how we frame topics, but who will contact us after events to say they found it to be a great experience for the university and the community.

Finding partners and an audience with a wide range of views was important not only for the quality of our Civic Discourse Project, but also for defining who we are as a school. Remember, our school is unique in that it arose as an intervention from the Republican-controlled state legislature and the Republican governor. So not only is the very existence of our department an implicit critique of existing departments, including political science, history, and philosophy, but it also brought fears among some that we would be a right-leaning political indoctrination project. We have found a lot of reasonable faculty and administrators who recognize that part of the mission of a public university should be the civic and political health of the state it serves, which requires civil disagreement and the exchange of ideas. As the founding director of the school, I wanted to show that we are not a political project in-and-of ourselves. We are an academic unit with a broader civic mission.

RJ: I appreciate that response, because I think exposing students to civil disagreement and debate is so needed. I am interested in bringing more of that to our campus here at the University of Mary, and I’m edified to see that you’re successfully navigating all this at ASU. If you can navigate these sorts of events at one of the largest major public universities in the country, we can do the same at a smaller Catholic university.

PC: The Catholic intellectual tradition has so much to offer here in terms of exchanging ideas, and I see that in your Mary College at ASU project. I came into education as a Catholic. I am a cradle-Catholic who spent some time away from the faith when I was in college because I thought I was so smart, and all my professors were so smart. But I came back to the faith through the Dominican friars at Oxford University while I was a graduate student there. In fact, I stayed and did an additional degree – a master’s in theology – and then went on to Boston College for my PhD in political science. I chose Boston College because it was Catholic, and I wanted the full breadth and depth of liberal education that the Catholic intellectual tradition provides. And I’ve been able to take that tremendous Catholic education through my career teaching at the Air Force Academy and now at ASU. I’m in a secular university, but I’ve taken the Catholic mission and spirit of education into this new project, a department devoted to civic thought and leadership blending liberal educational and civic education.

An interview with Msgr. James P. Shea

The Catholic university is, in essence, a Christian community comprised of believers who share life together and pass that life on to others.

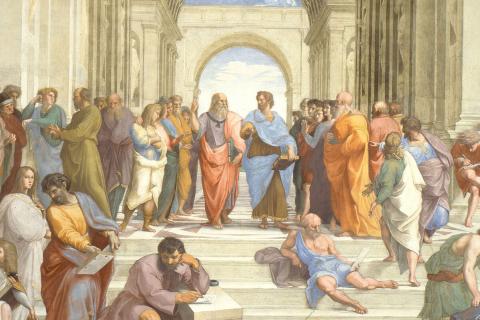

A public speaker series or a curriculum that emphasizes civil disagreement and civil debate about the most important human and political questions would make sense at a Catholic university. Catholic education has been engaging in that for almost a thousand years! I would date it back to St. Thomas Aquinas and the University of Paris. Catholics have always wanted to know both their faith and the created world around them. They’ve wanted to form and understand human and civic institutions. You don’t have to choose between studying the Faith or engaging in civic discourse. Catholic education has always held up both.

Over the past five years, I’ve had the opportunity to shape a curriculum. A small set of us designed undergraduate degrees, an undergraduate minor, and a new master’s degree in classical education and leadership. This gave us the opportunity to restore in a large public institution some of the breadth and balance of the broader classical view of education, which sees teachers and leaders as servants in public and civic life. And this was guided largely by the classical and Catholic tradition of education. Catholic universities have a claim on forming students in intellectual virtue in the classroom and beyond.

RJ: You used the word “restore,” and I think that’s such an important word here. We’ve been trying to do something similar here through our liberal arts core, which all students must complete. So we’re attempting to address the larger question of how to form students broadly and teach them to think and engage. You’ve used the terms “liberal education” and “civic education,” so I’m wondering how you define them in your school?

PC: “Liberal education” and “liberal arts” are terms we used interchangeably here, and in our school we define them as “a higher education for free people to be full human beings and citizens.” The Latin root for “liberal” here is linked to our word “liberty.” So we’re referring to inquiry and research and debate, but in a particular way to preparing people to be free human beings in a free political order, which we would call “liberal democracy” or “constitutional democracy.”

I think we tend to forget in the United States that higher education is an elite experience: about one-third or fewer Americans will ever earn a bachelor’s degree. So the burden of a university – whether it be public or private, secular or religious – should include the burden of preparing leaders for the free political community in which we live. It doesn’t matter if a young man or woman is an engineering major, a science major, a health pre-professional major, or a philosophy major: they should be formed to help to sustain and perhaps even guide our free political community. Every university should have some kind of a liberal arts or general studies core that includes preparation to be a free human being and a responsible, formed, constructive citizen and potential leader.

So that’s a very broad definition of liberal education. In our school, we approach it by teaching great works of moral and political thought as they would be taught in philosophy, political science, and history departments. We have particular expertise in American political thought and the great debates in American political and civil life. We also have particular expertise in the foundations of economic thought from the classical period to the medieval period to the modern period, with Adam Smith being the focal point of modern economic thought. We have a track in our undergraduate curriculum in leadership and statecraft, and then our master’s degree brings all of those elements together: the moral and political dimension, American political thought and political principles, and leadership.

RJ: Since we’ve developed our liberal arts core, there’s been a change in our student body. We’ve started attracting a different type of student. And I would like to think that part of that arises from our liberal arts core changing how they think. In my school – education and behavioral sciences – I used to hear quite often, “Well, I need to get my liberal arts requirements out of the way so I can get on to my education.” But I think that has changed.

I was at a conference with liberal arts faculty from public and private universities, and there was a discussion on whether these courses are truly making a difference. In the professional world, we have measures – we have to for accreditation reasons. So it seems like our liberal arts core is making a difference, but do you have any assessments or do you know of any research as to the impact such courses have on the lives of students? Liberal arts colleges in general have been declining across the country – what has the impact of that been?

PC: I will offer a broader assessment that wouldn’t meet the criteria now used by higher education professionals for accreditation purposes, but I have two pieces of evidence worth considering.

The first piece of evidence comes from Derek Bok, former president of Harvard University and longtime thinker about higher education. Bok recently released a book entitled Higher Expectations: Can Colleges Teach Students What They Need to Know in the 21st Century? His answer is mostly that they are not. It’s a pretty tough book. Two of the topics he discusses as crucial are civic education – preparing young men and women to be American citizens in the sense of informed, engaged, instructive members of a free political community – and ethics education. To me, that is the course of a classical liberal arts education. The origins of that can be found in the Greeks and the Romans, but the university itself was invented by Catholics in the medieval era who were able to pull together the classical tradition and the Christian faith tradition. So here is Derek Bok at the beginning of the twenty-first century saying that we have a big problem here in American higher education and that there are massive deficits in how universities are defining themselves around civic and ethics education. And to me the answer to that deficit is to restore a genuine liberal arts core that includes a civic education component, regardless of whether the institution is public or private, secular or religious.

As people who work in higher education, we can’t see the dysfunction in our society and claim that universities have nothing to do with it. We can’t say, “Someone else is the problem, not us.” That’s not a good answer.

So if you’re seeing success in attracting students, economists would say that you’re meeting a market need. But Derek Bok is onto the same thing: people are not only looking for a narrow vocational experience and advancement, but they’re also looking for meaning in their life. They’re looking for vocation in the larger sense. They’re asking, “What is my calling? What does it mean to be a human being? What does it mean to be a member of this community? What could I do to lead and to serve?” So if the liberal arts courses you’re offering are getting a response from students, I would say that it makes perfect sense. They provide long-developed answers to who we are as human beings, what our nature is, and – in the past 500 years or more – what it means to be a free citizen and a constructive member of a political community.

The second piece of evidence I would provide is sort of on the negative side, as well. If you look at America’s political and civic culture in the past two decades, there are plenty of moments where some of us have said, “What a bad moment we’re in. Surely it can’t get worse.” And then it gets worse, right? And the cycle has spiraled down. I think we have almost become accustomed to political violence being regular. There have been moments of regular political violence in American history – I’m thinking of the Vietnam War protests and civil rights protests of the 1960s and 1970s, for instance – but to have the kinds of political violence we’re having now about racial justice issues and even just the general left-right issues is alarming. That should not be accepted as normal in any way.

What are the root causes of that dysfunction? The political polarization and dysfunction we’re seeing is not just in political campaigns and political journalism, but is in our universities, as well. And now as you can see in the debate over critical race theory, it’s in our K-12 schools, as well. It’s everywhere. So this kind of intellectual-civic-political dysfunction has arisen as we’ve given space to more radical voices who feel rewarded for being on the extreme ends of the spectrum, both on the left and on the right.

It’s undeniable that in the past 50 years public and private universities have gutted their liberal arts cores and civic education requirements. There are a few public universities that still have them – Texas, Florida, and a few other states have some requirements for American government courses, but it’s not always clear that those courses are adequately embedded in a liberal arts core. And that matters. Try to read the Declaration of Independence, for example, and really understand every word of it. To do that, you have to have a decent liberal arts education. Take the last sentence: “We mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.” What does sacred honor mean in relation to rights? At the beginning of the document they claim that we have rights to life, liberty, and property, and now they’re pledging to give up those rights for each other. You really need a broader philosophical, historical, and human context to understand the document. Why is there a divinity invoked four times in the Declaration of Independence? Who or what is that divinity? What is the sacred honor referenced in the final line?

So I would cite those two kinds of assessment. Derek Bok is not to be dismissed: if he says there are massive holes in American higher education including in liberal and civic education, we have to take that seriously. And then we can look around at our political and civic culture. As people who work in higher education, we can’t see the dysfunction in our society and claim that universities have nothing to do with it. We can’t say, “Someone else is the problem, not us.” That’s not a good answer.

RJ: I’m interested by how often you’ve mentioned civic education, and by how you’ve tied deficiencies in civic and liberal education to civic dysfunction. I don’t know that a lot of liberal arts cores at universities provide much space for civic education requirements. Is that the sort of thing that can be accomplished in just one course? I don’t mean one course in isolation, but I’m wondering how universities could easily adapt to include civic education.

PC: If it had to just be one course, I would say that it should be a combination of liberal education and civic education. I think liberal and civic education should be understood partially within the American context, but it’s really part of a universal human phenomenon, as well. What do we mean by rights? What do we mean when we say human beings have an endowment of rights by nature or by a Creator? Why is our nation founded on this conception of human nature? We have to be able to answer these questions to understand what it means to be free. So that one course could hopefully provide a foundation for answering those questions and point students toward other kinds of courses they would want to take.

Foundations, The Catholic Intellectual Tradition

When faith and reason are properly understood, it becomes clear not only that do they not contradict, but also that faith has a central role to play in the project of higher education.

This deficit in civic education and liberal arts education in most universities and colleges is connected to changes we’ve seen in the understanding and practice of leadership that we’ve seen over the past several decades. The term “leadership” is the more modern and democratic – small ‘d’ democratic – term for the concept of statesmanship. To be a statesman or stateswoman is to be a leader of some ethical integrity who is committed to serving the rule of law and constitutional order of a free political order. So this has really become more of a possibility in the past several centuries with the rise of republics and liberal democracy. Such a leader could arise within a monarchy, but it would have to be a monarchy firmly committed to the rule of law. But over the last 30 or 40 years, as we’ve pushed aside the broader liberal arts foundations of education, leadership has become a more technical and narrower term. Today, schools of business, management, and even psychology talk about leadership in a narrow, social-scientific way. So what our school is attempting to do at ASU is to restore some of the broader and higher view of what leadership is in a free political order, which means reconnecting it to its classical and medieval and early modern roots to prepare students for engagement in their professions and civic life.

Our master’s degree was largely designed for teachers interested in classical curriculum schooling, but it benefits other graduate students, as well, because leadership relies upon a grounding in liberal arts learning and understanding the foundations of the concepts of freedom, politics, and community.

RJ: You mentioned that civic and liberal education has roots in universal realities, but also that your department explores it in the American context. I was wondering how your Catholic faith impacts the way you approach civic and liberal education. How has it influenced the way you’ve approached the creation of your school at ASU and how you understand the mission of that school? How has your faith guided you?

PC: It’s fundamental for me. I’ll answer it like this: I would like to think that the president, provost, and the dean made an excellent choice when they selected me to be the founding department head of this school, but that all raises a question: why me? Why did they want a professor of political philosophy from a federal military academy who has focused on American political thought? I think a lot of that comes down to the great books program I developed at the Air Force Academy. At the academy, like all military academies, there is a strong emphasis on science, technology, and engineering. So there was a little too much of the spirit you had mentioned earlier of seeing liberal arts as something to get through before “real” education can begin. Our liberal arts honors program was offered to the most excellent cadets saying, “We don’t want you to just ‘get through’ your liberal arts courses, but you can love them and enjoy them and see them as a crucial part of who you will be as a citizen and an officer and a leader.” ASU’s leadership wanted the broad liberal arts approach we offered to cadets at the Air Force Academy to serve as a foundation for the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership.

But all of that hinges on the question of why I had such a background and why I was able to bring that to my time at the Air Force Academy. And the answer to that is simple: I had it because I am Catholic. In the latter part of the twentieth century in American universities and at Oxford University, there was still a small, vibrant element that could be found in philosophy, history, theology, and political science departments of people who knew and loved the Catholic educational tradition and were passing it on. That’s how I was shaped. So even though I was at a secular institution and am now at another secular institution, I’ve brought that same element to my work.

There have been several occasions in which I’ve brought candidates for political philosophy and intellectual history faculty positions to the dean, and he has asked me why I keep bringing forward so many candidates with PhDs from Catholic universities. And my answer always is, “Where else do you expect me to find them? Do you want me to find someone who knows the full classical tradition from UC Berkeley? That person may exist, but the odds aren’t great there.” So it’s not like I’m hunting for Catholic PhDs, but as it turns out, each time we conduct a search, get a pool of candidates, and narrow the pool down, the Catholic tradition tends to be the common trait shared amongst the candidates. I think for any Catholic involved in higher education, it doesn’t come as a surprise that what we’re lacking at ASU is exactly what great Catholic universities can still provide.

RJ: Dr. Carrese, you give me hope. I appreciate your insights. Thanks for your time.