During the last many decades, Catholic life has been dominated by the question of tradition: what it is, whether and how it is important, and how it should take its place in the life of faith.

“Jesus said to them, ‘Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’” (Matthew 13:52).

“Salvation comes, not from the destruction of tradition (progressivism) or the archaeological neutralization of tradition (traditionalism), but only when the Church, the bearer of tradition, penetrates to its true center, to the life at the heart of tradition, to that community with God, the father of Jesus Christ, that is revealed only through faith and prayer. Only when this occurs can there be that true progress that leads to the goal of history; to the God-man who is humanity’s humanization” (Pope Benedict XVI).

During the last many decades, Catholic life has been dominated by the question of tradition: what it is, whether and how it is important, and how it should take its place in the life of faith. This has not just been an occupation of academic theologians; questions concerning Catholic tradition have increasingly been taken up in popular books and talk shows, on the internet and in podcasts, and these conversations involve strongly held arguments and opinions that touch our politics, our parishes, our schools, and our own attempts to live a faithful and coherent Christian life. This article is meant as a brief aid toward gaining a Catholic mind on this important and vexed question of Catholic tradition.

1. Tradition in Christian understanding

A reference to Christian tradition comes up in one of the earliest books of the New Testament. During his second missionary journey, St. Paul visited the Macedonian city of Thessalonica. His preaching had a significant effect and persuaded many Jews and Gentiles to embrace the new faith. Paul’s time in the city was brief. His success stirred up violent opposition, and after only a few weeks he and Silas had to slip away by night. Paul then wrote two letters to the Thessalonians to encourage them in their newfound faith. The second of those letters included this exhortation: “So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter” (2 Thessalonians 2:15). A few years later Paul wrote something similar to another recently established Church in Corinth: “I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I have delivered them to you” (1 Corinthians 11:2). We usually connect the idea of tradition with great age: we call something traditional because it has been around for a long time. Yet here Paul is speaking of traditions that originated in the mission of Christ just a few decades previously and that were handed on to newly converted Christians only a few months before.

The etymology of the word “tradition” gives a clue to St. Paul’s meaning. Tradition comes from the Latin word tradere (in the original Greek the word is paradosis) meaning "to hand on, to deliver, or to entrust." Paul had been entrusted by Christ with the message of the Gospel. His task as a missionary was to “hand on” that message, to entrust it to others. Tradition was thus for St. Paul a shorthand way of referring to the Gospel and all its demands. Another pair of passages in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians underlines this meaning. He writes: “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me’” (1 Corinthians 11:23-24). He writes further on: “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4). In both of these passages dealing with essential Christian beliefs, Paul speaks of first receiving and then delivering the truth in question. The word translated as “delivered” is the verb form of the Greek word paradosis, or “tradition.”

This brief foray into scriptural terminology makes clear that the essence of tradition, as the word is used by St. Paul, is intrinsically tied to the notion of truth. Tradition for Paul meant the truth of the Gospel as first taught by Christ, handed on to the Apostles, and delivered to others as the foundation of the Church and the basis of the Christian faith. In this sense, tradition refers to what has been revealed by God as perennially true, what Paul elsewhere called the deposit of faith. It has now been two thousand years since the Gospel was first preached and handed on by the Apostles, so the Christian tradition now has the flavor of something long-standing. But Christians value the traditions of the Gospel not mainly because they have been around for a long time, but because they have been revealed by God and are always true and ever fresh. They were as “traditional” in the first century as they are in the twenty-first.

2. Tradition and traditions

The word “tradition” has other related meanings that go beyond the scriptural use of the term. Many things of different kinds have been “handed on” to us by previous generations. Some are evidently more important than others. How are we to evaluate their relative significance? We might note three broad categories of tradition that have been recognized by Christians over the centuries: (1) the traditions that were handed on from the Apostles, usually called simply “Tradition with a capital T” or the “Apostolic Tradition”; (2) various expressions of Christian faith and life that have arisen and have been handed on by Christians in different times and places and are often called “Ecclesial traditions”; and (3) cultural practices of all kinds that are passed on from generation to generation.

The Catholic Catechism explains the difference between the first two types of tradition just noted, supplying a distinction that is itself part of Catholic tradition:

A third kind of tradition can be noted: namely the whole pattern of living and thinking that every society hands on to its younger members. Customs of language, education, governance and social ordering, economic practices, an entire way of life down to detailed matters of food and dress, all fall under this category. Some traditions of this kind are of great value, expressing and incarnating important human truths and reflecting something of God’s original intentions in humanity’s creation. Many are of a morally neutral character, like a particular language or a local cuisine. Some are unhealthy or morally evil, the result of fallen humanity’s habitual corruption.

The Church deals with these three kinds of tradition differently. As to the first, the Apostolic Tradition, the substance of divine revelation itself, the Church carefully protects and proclaims it and lets nothing obscure or replace it. Regarding the second, specific ecclesial traditions, the Church honors them and values them, guiding, nurturing, and adjusting their practice so that they can continue to be effective means of incarnating the truths of the Deposit of Faith. In dealing with the third type, human traditions of all kinds, the Church sifts and sorts them, supporting and encouraging what is valuable and working to mitigate or eliminate what is harmful or evil. The careful handling of these different kinds of traditions has given the Church a remarkable quality of being both changeless and culturally adaptive. Founded on the perennial truths revealed by Christ, the Church is an immovable rock amid a world of constant change. Attentive to the task of clothing the truth in the changing languages and cultures of humanity, the Church puts down roots in human soils of all kinds, affirming and transforming those cultures in the process. As a result, the Church has been a potent agent of both change and continuity in the various cultures it has encountered and inhabited.

3. Christianity and Tradition

Respect for traditions of all kinds has been a universal human practice. Virtually all human cultures have honored the traditions they have received from their forbears and have attempted to live within the contours of what was handed down to them. It has been a general cultural rule that what was new was suspect and needed to prove itself, while what was time-tested was respected and followed. To some degree this has been a matter of simple survival in an often-hostile physical and social environment. If every generation needed to learn for itself the difficult skills required for staying alive and maintaining social order there would be little chance of continuing in existence. Living by inherited traditional wisdom has made good practical sense.

Christians value the traditions of the Gospel not mainly because they have been around for a long time, but because they have been revealed by God and are always true and ever fresh. They were as “traditional” in the first century as they are in the twenty-first.

Seen against the backdrop of the world’s cultural history, the coming of Christianity has brought a dynamic element into the static traditions of human societies. While Christians have insisted on faithfulness to the revealed Tradition that was handed on by the Apostles, in other respects they have been less tied to human traditions than most other human cultures. The striking characteristic of societies such as the Egyptian, the Mesopotamian, or the Chinese has been their continuity through time. Even the Graeco-Roman world greatly venerated what had come down to them from their ancestors and looked askance at whatever was new. For example, the Romans respected the antiquity of the Jewish religion despite the difficulties they sometimes had with their Jewish subjects. Christianity, on the other hand, was not easily respected by them, because it involved a set of doctrines that were perceived as novel. Only when the Church Fathers were able to connect Christianity to the philosophical and educational traditions of Hellenistic culture did it become palatable for the society as a whole.

In contrast to many of the great ancient cultures, societies influenced by Christianity have had a dynamic quality that has been more amenable to change and to the reception of new ideas. This dynamism is rooted in the Christian understanding of history as an epic drama written by God whose plot is developing over time and leading somewhere decisive. The ideal of spiritual and societal equilibrium sought by the Romans or the Chinese has found no counterpart in Christian societies, where the longing was not for endless stasis, but for the imminent return of Christ and the radical transformation of human life. It is not an accident that the society of the West, deeply influenced by Christianity, has for better and for worse drawn the rest of the world into its dynamic cultural expression and historical development.

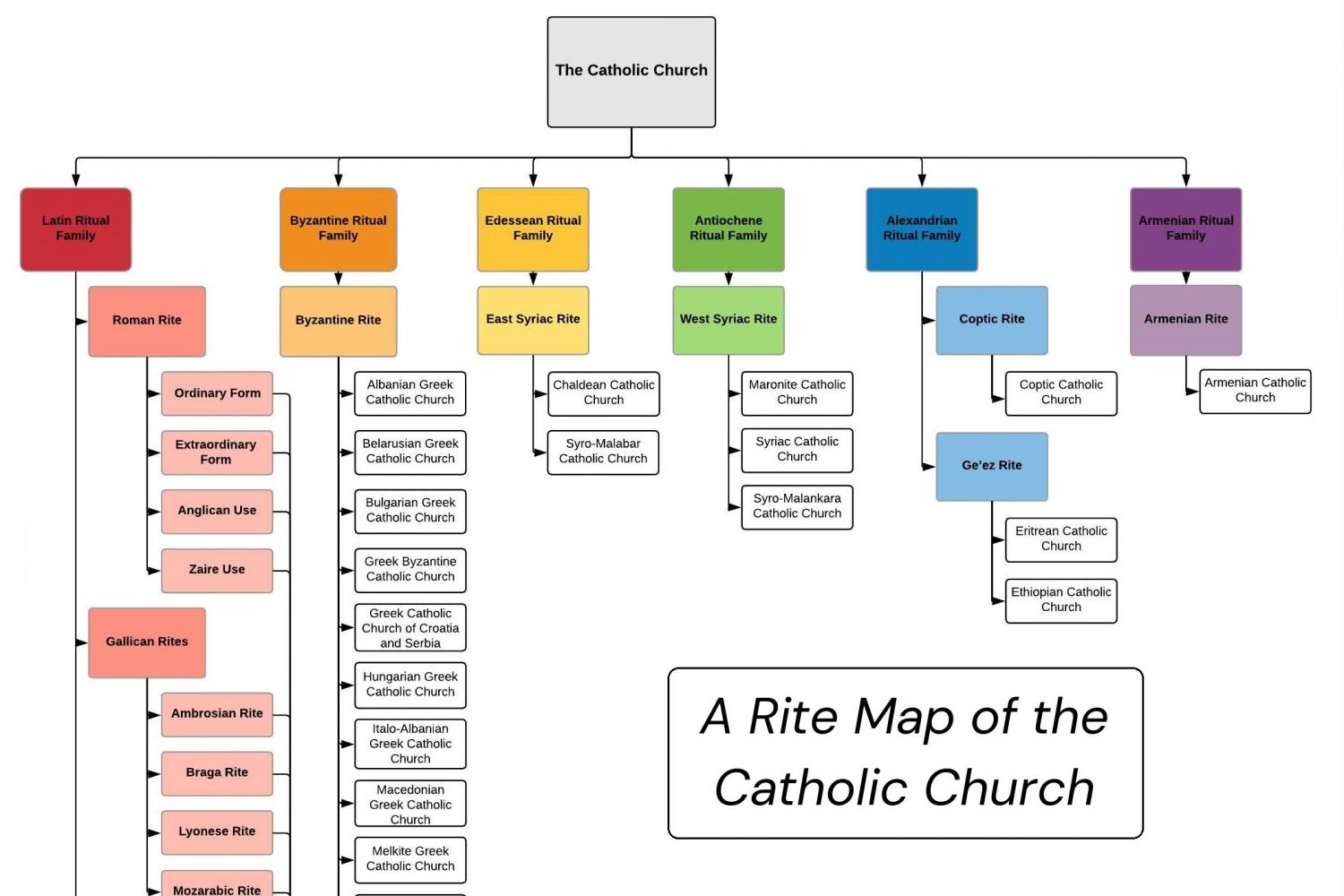

Christians have thus had a paradoxical relationship to what is traditional. On the one hand they have understood the Apostolic Tradition to have been revealed by God as perennially true, and have accorded it an authority that goes beyond any merely human set of ancestral customs. On the other hand they have recognized that God in Christ is in the process of making all things new, and that the Holy Spirit is not a blind force but a divine Person who engages humanity in every age and place according to his own providential designs. To take one example out of many: the development of religious orders over the centuries has been a consistent integration of the old and the new. When the monastic movement first populated the desert, or the mendicants first left the monastery and went begging, or the apostolic societies formulated their plans of action, or Mother Teresa went to the streets with her sisters, new ground was being broken, new modes of living and communicating the faith were being developed, and inevitably a good deal of opposition was incurred from some who were uneasy with this break from long-standing traditions. But each of these developments, and many others with them, can be seen as branches on the trunk of the same tree. In matters of the Apostolic Tradition they have agreed and have maintained unity with each other, even while some of their specific ecclesial traditions have differed. Something similar might be seen in the development of liturgical rites. The same Eucharistic sacrifice was celebrated everywhere according to a shared understanding of its meaning, even as it was differently expressed in the cultural clothing of the Greeks, the Latins, the Syrians, and the Egyptians. When St. Augustine spoke of Christ and Christianity as a beauty that was “ever ancient and ever new,” he was touching on this paradox. Christianity has been both the oldest and the youngest thing on the face of the earth.

4. Why the question of tradition is currently so problematic

For much of Christian history, no one seriously questioned the need to honor both the Apostolic Tradition and the local ecclesial traditions that had been handed on and developed from the earliest times. There were battles over the precise content of the Apostolic Tradition, and there were constant efforts to maintain the purity of local traditions that could tend over time to take on aspects of worldliness. But it was understood that the point was to live by the truths and the wisdom that had been handed down. A serious break in this pattern came at the time of the Reformation. It is true that the Protestant Reformers were not attempting to do away with the tradition. The whole of their claim was that the Apostolic Tradition, which they tended to confine to what was found in the Christian scriptures, had been lost amid a welter of what they considered human traditions and that the Gospel message had become obscured. Yet their movement, especially in its more radical forms, called into question so much that had long been held as part of the Christian patrimony that it tended over time to overthrow the Christian balance of “ancient and new” and fostered an attitude of dislike for all things traditional.

A few hundred years ago a current of thought and life began to set in that has systematically discarded whatever came from the past and has looked forward in a singular way to what is coming in the future. This way of thinking arose from the dynamic soil of Christianity, but while its adherents maintained the Christian idea that human history was an ongoing story of transformation and likewise embraced the promise of a new heaven and a new earth, they abandoned the idea of any revealed, perennial truth. The balance between the old and the new, between love for what was handed on and readiness for what was coming, was lost. Furthermore, our remarkable progress in the applied natural sciences has meant that in many matters relating to our interaction with the physical world, what is new has generally been better, often spectacularly better, than what was handed on. Under the imaginative potency of that technological development we have made the illogical but understandable category error of thinking that the same superiority of what is new over what is traditional applies also to spiritual and moral realities. Horse-drawn carriages are outmoded; the same must be true of sexual morality. Our understanding of particle physics goes way beyond that of our ancestors; the same must be true of our understanding of God.

Not surprisingly, this attitude toward the “bad old things” and the “good new things” has also affected the Church. The nineteenth century saw the rise of “liberal Christianity,” a kind of halfway-house between Christianity and progressive unbelief, in which certain Christian moral ideals were maintained along with a sentimental attachment to Christianity’s founder, while the perennial truths of the faith were set aside as being old and therefore outmoded. This phenomenon of liberal Christianity arose first in the Protestant world. Among Catholics it became a point of sharp contention during the Modernist controversy of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and has continued to be a cause of serious disagreement concerning the authentic interpretation of the Second Vatican Council.

At the heart of modern progressive religion – for it is a religion – lies the claim that we are now living in an age different from what came before it, not just accidentally in the way that every age has its uniqueness, but essentially. What has pertained in the past no longer applies to this new age. In the progressive gospel, the Christian belief in a coming heavenly age of perfection has been secularized and brought into historical time: we have left behind us the age of oppression and are now emerging into the age of freedom, and the ongoing revolution in its many forms is bringing about the fulness of that new age of humanity. This way of thinking has imbued our atmosphere and has tended to provide unexamined first principles even for many people who do not sign on to the details of a specific revolutionary program. It is a hard thing to avoid being affected by the pervasiveness of the progressive paradigm; one sees these hidden first principles at work on all sides of our current political, social, and religious controversies. Catholics taken by the progressive mindset have applied this dogma to the Church. They have conceived an instinctive and profound dislike for the two-thousand-year heritage of Catholic doctrine and history, seeking to bring about what they have sometimes called a Copernican revolution in the Church’s self-understanding. They have coupled an un-Catholic contempt for historical expressions of Christian truth with an un-Catholic eagerness to imitate a secularizing culture in moral and spiritual matters.

In the face of this apostasy, and confronted by a culture that has increasingly despised everything traditional, some in the Church have reacted not only by insisting on maintaining the perennial Apostolic Tradition as revealed by God and honoring the traditions that have expressed it, but by elevating certain particular and local ecclesial traditions to the same level of authority that Catholics have always accorded the great Tradition. When they heard the cry: “The new is good, the old is bad!” they responded with its sweeping photographic negative: “The new is bad, the old is good!” The response is understandable, but it is seriously out of step with genuine Catholic tradition. Ironically enough, as Bishop Daniel Flores has observed, “a Catholic form of traditionalism can morph into just another (boring) version of Modernism when it becomes consumed with deconstructing the living magisterium of the Church through subjective criteria.” The Catholic traditionalist can tend to consider the Church through the optic of contemporary political categories while unknowingly adopting the modern progressive assumption that our age is essentially different from all others. The danger here is to take up the modern ideological terrain and then simply turn the progressive dogma upside down. Broadly speaking, instead of idolizing the modern age and denigrating the past, one can denigrate all that is modern and idealize the past. For the progressive believer, the golden age lies in the future and we need to hurry to meet it. For the traditionalist, the golden age lies in the past and we need to get back to it.

5. Two Tests

Some practical litmus tests can be applied that can help to see whether such hidden progressive tendencies are present in our own thought and behavior. One has to do with the overall atmosphere we engender. It is part of progressive dogma that the evil of the world comes not from personal sin, not from the wound of our nature, but from external sources, structures of evil that need to be destroyed so that the inherent goodness of humanity can emerge. For this reason every progressive cause is necessarily revolutionary: its moral demand is to tear down whatever out there has been identified as the source of evil. Spreading the progressive gospel is by necessity a call to violent or disruptive action, and progressive believers make converts by inciting people to anger and anxiety. Given the progressive mindset, this evangelistic tactic makes sense. Only if people become worried and enraged will they be motivated to embrace revolutionary action. Christianity, on the other hand, makes its way in the world and announces its Gospel in very different terms. The Christian call is to do battle, but mainly with self. It is a call to repentance and humility, to love and reconciliation, to union with God. If as a group of Christians we find ourselves enveloped in an air of anger about what is going on in the Church and the world and we regularly try to get others angry, if our thoughts and energies are mainly directed at seeking out and eradicating external enemies, if a sense of moral superiority because of our correct practices has gained the upper hand among us, we can be sure that the deep structures of modern progressivism are unwittingly present.

A second litmus test can be found in the progressive tendency to settle upon a simplistic solution to the complex problem of human evil. Every progressive cause produces a “silver bullet,” the one thing that will do the job in overcoming evil. It is the philosophy of the “if only.” If only we do away with the aristocracy; with the bourgeoisie; with the Church; with patriarchy; with heteronormativity; with Jews; with white privilege; with our flawed human “wetware,” everything will fall into place. This way of thinking is one of the sources of our society’s current proliferation of conspiracy theories that hope to identify and thus overcome that one source of our evil. Christians who have been influenced by the progressive mindset can be swayed by similar simplistic views in a variety of directions. As an example, some among both liberal and traditionalist Catholics have identified such a silver bullet in the practices of the liturgy. If only we can change the liturgy, the Church will be launched into its new progressive form. If only we can retain a specific ecclesial tradition of the liturgy, all the ills of the Church will evaporate. Liturgy is indisputably of central importance in our Catholic life and worship, but when seen through the reductionist lens of our prevailing cultural mindset it can come to be viewed as the single issue upon which everything else hangs.

The Catholic traditionalist can tend to consider the Church through the optic of contemporary political categories... The danger here is to take up the modern ideological terrain and then simply turn the progressive dogma upside down.

6. Gaining a Catholic mind concerning tradition

“Tradition is the living faith of the dead, traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. And, I suppose I should add, it is traditionalism that gives tradition such a bad name” (Jaroslav Pelikan).

The authentic Catholic view rejects both of the options – progressivist and traditionalist - mentioned above. Catholics know that every age from the first coming of Christ to his return share the same fundamental conditions. In every age both God and the devil are on the move, human hearts are being sifted, and the Gospel is continuing to make its way among the languages and cultures of the world. The Catholic mind recognizes that the “counter-revolution” is not a revolution in reverse, which would be a capitulation to secular thinking; it is the re-articulation of perennial truth and a recovery of Christ’s balance of the old and the new. The Catholic mind refuses to be co-opted by a false view of history, and it reasserts the important distinctions that apply in every age between Apostolic Tradition, particular ecclesial traditions, and human traditions.

To be a Catholic means to be traditional in the full understanding of that word. It means loving the Apostolic Tradition: the deposit of faith handed on by the Apostles, eminently preserved in the Scriptures, remembered by the Church, and interpreted authoritatively by the Church’s magisterial gift. When St. Paul wrote to his disciple Timothy concerning his duties as a bishop, he summed up his letter by saying: “O Timothy, guard what has been entrusted to you!” (1 Timothy 6:20). That task of guarding the Good News of Jesus has been the joy and duty of every disciple. In addition, to be Catholic means to honor the many Christian traditions that have arisen through the centuries and that the Church has taken to its heart, even those of times or places that have no connection to us. It means avoiding the perilous temptation of thinking ourselves wiser and holier than our ancestors. This is what G. K. Chesterton meant when he wrote, “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to that arrogant oligarchy who merely happen to be walking around.”

At the same time to be a traditional Catholic means to recognize the difference between Tradition and traditions, and to willingly honor the authority given by Christ to the Church’s magisterium for ordering its ecclesial traditions according to the Apostolic Tradition. Those who have embraced a Catholic mind are reticent to change the forms by which the Apostolic Tradition has come down to us, knowing that rapid change, even concerning that which is not essential, can call into question revealed truths. Yet they will equally avoid the temptation to absolutize cultural expressions of the faith. They will remember Christ’s admonition to the Pharisees: “You leave the commandment of God, and hold fast the tradition of men. You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God, in order to keep your tradition!” (Mark 7:8-9). Serious-minded traditional Catholics will feel drawn to and rejoice in particular ecclesial customs, but they will remember that difference does not mean disunity wherever the Apostolic Tradition is honored and the authoritative voice of the Church is present and giving guidance. Above all, they will strive to maintain unity and the bond of peace with all genuine fellow-believers, loving the Church, preserving their hearts from anger or pride (for God opposes the proud even when they are right), and fostering in their own communities a visible unity in worship without affectation.

In this time of increasing extremism in the wider society, with so much anger and vitriol captivating both our political order and the public discourse of Catholics, it has become critically important for those who have been given the grace of Christian discipleship and the task of guarding what has been entrusted to us to embrace the whole of the Catholic mind regarding tradition. We can do so in a spirit of joyful repentance, faithful obedience, and hope-filled trust. In response to God’s grace for our times we will want to become like that scribe spoken of by Jesus and trained for the Kingdom of Heaven, and who therefore knows how to bring forth both the old and the new from the treasure of our faith.

Watch the Primer Video

Fundamental Principles of Catholic Liturgy

For over three thousand years, God's people have understood proper liturgical practice to be an essential aspect of what it means that God’s will “be done on earth as it is in heaven.”

The Synthetic Impulse in Catholic Life

Most Rev. Daniel E. Flores

St. Hildegard demonstrates the synthetic impulse of the Christian vision, which recognizes that all of Creation is connected and that a mystery runs beneath all things, holding them together.

The Catholic Problem of History

Many common historical claims leveled against the Church fall flat: they fail to recognize what the Church claims to be and what it claims to offer.

Photo Attribution A: "A Rite Map of the Catholic Church" used with permissions via /u/shotofdepresso.