Many common historical claims leveled against the Church fall flat: they fail to recognize what the Church claims to be and what it claims to offer.

Perhaps you have found yourself in this sort of a situation: you are in a conversation that touches on Christianity, and at a certain point a historical Molotov cocktail is thrown into the middle of it, “Yes, but what about the Crusades (or the Inquisition, or the trial of Galileo, or the imperialistic colonial missionaries, or the Renaissance popes with their mistresses and poisons)?” There you stand, stuttering, partly because such questions often have no applicability to the current conversation, partly because you do not know very much about any of these things, and partly because you are sure that the person tossing the cocktail does not know much about them, either. There seems to be nothing that can be said or done: it is simply a conversation stopper, which might have been the point of flinging the cocktail in the first place.

Part of the difficulty with such situations is that many modern people have dim notions of these historical claims that have been passed on as part of the tradition of anti-Catholic propaganda that supposedly everyone knows. People have picked them up somewhere, and they think they are dealing in settled facts. When one takes the time to investigate these various failures of the Church, however, one finds that they are seldom what they have been reported to be. In many cases it turns out that they were not failures at all, or that they were failures in a way quite different from what has been reported, or that while failure was involved the degree of failure has been exaggerated greatly. The disparity between what “everyone knows” and what actually can be ascertained by historical study is often very striking – even astonishing – and steady historical research seems to have little influence on dispelling these errors in the popular mind.

There is something anomalous about this. No one, least of all Christians, should be surprised at finding sins, faults, and errors of judgment by Christians in the historical record; indeed, even the best members of the Church are sinful humans of limited talent and wisdom. There has never been a lack of nominal believers – and even outright hypocrites – within the Church to further compound the problem. Beyond that, there are always differing judgments about matters of history, occasional mistakes, or even purposeful misrepresentations in historical treatments of any kind. History is not an exact science, as the human past is a complex matter and historical data are often scarce or incomplete. In the case of the Catholic Church, however, the magnitude of the errors concerning its history, the vehemence with which the errors are held, and the great difficulty encountered by serious historians in correcting the historical record are without parallel, which all seems to demand some kind of explanation. It can be troubling for the believer to be confronted constantly with the supposed dark past of the Church. Christians who do not have the time to sort out the historical record can come unconsciously to accept the errors as simply true.

This brief article is an attempt to explain why this anomalous situation exists and to give some principles of historical analysis that can help the honest inquirer gain a more accurate picture of the Christian past.

The historical problem might be put simply this way: the Christian Church, despite the flaws of its members, is on any fair hearing among the most impressive institutions in the history of the world. It has been at the heart of innumerable civilizational achievements and has been instrumental in the development of just forms of government, notably democracy. In addition to being a consistent patron of the arts, it has preserved and creatively developed human education and has provided a fertile soil for the development of science. The Christian Church has been decisive in the repudiation of slavery and a great promoter of human rights, and it has been by far the largest charitable organization that the world has ever known. Yet, despite these and other remarkable achievements, it is often held to be the source of all manner of evils, and to be among the worst, or even the very worst, of human institutions that ever came to exist. Its contributions tend to be denied or minimized, and its sins and errors exaggerated or presented in an egregiously one-sided way. Why?

As it happens, there are reasons for this inaccurate and often unfair historical treatment, reasons that go to the heart of the drama of the human race and the place of the Church in that drama. These reasons do not excuse the historical errors, but they help to make those errors explicable and can point to ways of viewing the historical record with greater accuracy.

Reason #1: The Church is unique among human institutions in its essence.

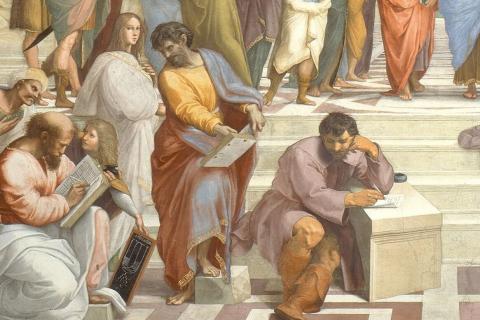

We never want to stray far from Aristotle’s fundamental maxim about the proper way to investigate any given aspect of reality: one studies a thing according to the nature of the thing being studied.

One of the roots of the historical problem we are addressing is to be found in a serious misunderstanding right at the start. The Church needs to be studied with a different lens than other human institutions insofar as it is unlike any other human institution, not just in its details, but in its essence. To say this is not to indulge in a kind of Christian jingoism or to insist that Christianity is somehow special because we happen to be part of it. The uniqueness of the Church comes from a fact of its nature. Because Christ is God himself come among the human race, and because the Church is the Body of Christ – the mysterious but real incarnation of Christ’s Holy Spirit on earth – the Church has a quality that no other organization or institution possesses: it is by its nature both human and divine.

As to its humanity, the Church shares with other human institutions all the various aspects of institutional life. It has a government, a set of ideals, a way of gathering, a multitude of cultural expressions, and an economic and a social existence, the same as any other large assembly of humans organized for a particular purpose. It is likewise comprised of people who are of the same flawed and sinful stuff as those around them. In all these ways and in many others, the Church is similar to other human organizations and can be viewed and examined as one institution among many of a similar kind.

At the same time, and more essentially, the Church is a divine institution. Christians point to this when they recite creeds that call the Church “holy.” The Church is holy not because of the impressive quality of its human members, but because it is the dwelling place and the visible clothing of the invisible Holy Spirit. God himself resides in the Church and reveals Himself through it in an entirely unique way. This presents certain difficulties in understanding its history.

It is instructive that a similar difficulty presents itself in studying the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus was human, with all the characteristics of other humans. It is therefore possible to view him simply in his human qualities and relations. He lived and died in a particular place; he came from a specific family; he had the same outward possibilities and limitations as other members of the human species. Many who study his life put him alongside other influential people who seem to be in the same category: Moses and Mohammed; Lao Tzu and Confucius; Buddha and Zoroaster. Given the human nature of Jesus, this is understandable – but it is a serious error. Jesus was not only a human. He was also the divine Son of God. In this he is radically unlike all those others: he is in a category by himself. In coming to terms with his character and his history, his divinity will need to be taken into account.

The Church is holy not because of the impressive quality of its human members, but because it is the dwelling place and the visible clothing of the invisible Holy Spirit.

One sees the quagmire that engulfs those who view Jesus only from his human side. They cannot deny that Jesus has been hugely influential. They see that during the very brief time of his public activity he divided everyone who met him into two distinct camps: those who thought him so impressive that they worshipped him as God, and those who found him so evil that they thought he needed to be killed. This dramatic response demands an explanation. Why did Jesus so rivet all who heard him and provoke them to such opposite reactions? Why has he continued to be so potent a personality that he has become the most loved and the most resented human who has ever lived? There is no special difficulty in answering that question once it is understood that Jesus is both human and divine, God himself come among our race to confront us with our rebellion and to call us back to our true allegiance. Both the worship of him and the resistance he provokes have a clear explanation. When his divine nature is left out of the picture, however, it becomes necessary to look for other reasons for the intense and radically polarized responses to him. As a result, various false pictures of Jesus have been constructed to provide a plausible human explanation: we are given Jesus the political revolutionary, or Jesus the romantic breaker of rules, or Jesus the militant pacifist, or Jesus the crazed apocalyptic prophet. We are even given what is certainly the least convincing historical picture of Jesus among them all: Jesus the “nice guy,” the sadly misunderstood moral teacher.

Something similar happens when those who deal with the Church’s history fail to take into account its divine quality. Christians know that the intense response the Church has provoked through the ages has little to do with the impressive talent or the dark deeds of its human members, and everything to do with the presence of the Holy Spirit within it. When the Holy Spirit is taken out of the picture, however, merely human reasons need to be found for its powerful effect on human affairs. Through such a merely human lens, the Church’s ability to gain ardent love and loyalty becomes a sign of its seductive and manipulative character. The Church’s remarkable vitality and continuing influence is the result of secretive and highly organized conspiracies. The implacable resistance it has often inspired can only be due to the horrible crimes it has perpetrated. Otherwise, how can one explain the fact that the Church has been the most consistently beloved and hated institution in the history of the world?

Reason # 2: The Church cannot be studied “objectively.”

Since the Church is the staging ground for God’s appeal to every member of the exiled human race, and since it is the privileged instrument through which he calls to his “straying sheep” to return to the Shepherd and Guardian of their souls (1 Peter 2:25), it is impossible for fallen humans to deal with the Church impartially. Maybe Martians, if they existed, could manage it. They might view the Church as something entirely apart from themselves. They could hear the appeal at its heart as not being addressed to them, and so could attempt an objective account of its life and its doings. No earthling, on the other hand – and here again the connection to the life of Christ arises – can stand aloof from the action of the Creator as he deals decisively with each of his fallen creatures. There are no “objective” human bystanders in the story of Jesus, no one who can view his life and hear his words from a disinterested vantage point. Everyone has a highly personal and deeply momentous stake in the truth or falsity of the Church’s claims, whether those claims are received joyfully, denied categorically, or ignored with a posture of indifference. Even human law notes the difficulty in being objective concerning matters that touch us closely. It is hard to give a fair hearing to those we love or those we hate. It is hard to maintain an impartial view when we have a serious personal stake in the matter. Hence the category of “conflict of interest” by which judges and jurors will be recused from a case, or evidence will be received with a grain of salt when such obvious personal interests are in play. When it comes to reporting on Christ and his Church, everyone has a conflict of interest. No one is simply impartial.

This is not to suggest that there can be no reasonably accurate picture of the Church’s history, or that recognized standards of good historical work should not be insisted upon: it is only to say that no one can pretend to be a disinterested party with no skin in the game. The modern discipline of history was developed largely during the eighteenth and especially the nineteenth centuries in post-Protestant and often post-revolutionary countries, where the mythic picture of progress was displacing an earlier overall Christian narrative of history. Most of the history of the West has been written by historians out of sympathy with Christianity, and often actively hostile to it for personal reasons of their own. Edward Gibbon, the eighteenth-century anti-Christian author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was the father of this school of historical writing, and advanced the highly dubious claim that the Roman Empire fell because of the rise of Christianity. It is therefore not surprising that, coming from such sources, widely differing accounts of the Church and its history have arisen and are still tenaciously held.

In this regard, it is suggestive to note that when the Church has been most profoundly opposed and most deeply detested, it has not been for its obvious sins and failures – though these have been common enough and have provided reasonable grounds for critique. The fiercest opposition to the Church has come from the Church’s stubborn adherence to the message of Christ. The Church gets along best with the wider world when it is least faithful to its Founder and Master. It suffers its worst attacks when it is most loyal to Christ’s teaching. Even much of the justifiable anger against the Church for the sins of its adherents has a particular intensity due to what the Church positively stands for. The uncomfortable call of Christ to repentance, humility, and moral discipline that issues forth from the Church can be more easily disregarded if the misdeeds of some of its members are kept in focus.

Reason #3: The Church is not utopian in its claims or in its effects.

One occasionally hears a comment that goes something like this: “Christianity’s day is past. It was tried, and it didn’t work.” If the matter is pursued further, one is then given a list of failures that prove the point. For over a thousand years in European lands, the Church was the dominant social institution in setting the ultimate goals and articulating the moral ideals of the society. What was the result? Did wars cease? Did greed and lust for power disappear? Was injustice eradicated, individually and socially? Were the most vulnerable members of society always well cared for? Were the Christians of those past times paragons of good behavior? At this point in the conversation, one of those “well-known” historical sins of Christianity will usually be trotted out to clinch the argument. With this, the matter is presented as clear and settled: "Christianity directed the whole of a civilization for many generations and it fell seriously short. We obviously need to come up with a different model to secure human happiness and to arrange for the perfecting of human society."

The careful historian will want to correct this picture in many of its details by noting that Christianity did in fact make a serious difference in all these areas: in lessening the ravages of war, in making inroads against slavery, injustice, and practices of rapacity, and in encouraging concern for the weak and the oppressed. Nevertheless, even given these reasonable adjustments, the picture in its broad outlines remains true: the so-called “Christian centuries” did not produce anything like a perfect society.

There is a fundamental first principle behind this kind of negative assessment, one that many moderns assume without reflection as a self-evident truth, but that Christians know to be profoundly false. That first principle is the denial of the reality of the Fall. Christians know that this world will never be a place of perfect justice, peace, and brotherly love as long as it is peopled by a race whose inner moral being is profoundly wounded and who are under the influence of dark and powerful spiritual beings. Those who deny the existence of the devil and who repudiate the idea of an inner moral wound see no reason that we cannot structure the world in such a way as to eradicate most of its evil. Instead, they come up with all kinds of schemes to accomplish their purpose. Hemmed in by their utopian assumptions, they naturally view Christianity as another such scheme for human perfection, and since it has not produced the utopian world for which they hope, they pronounce it a dismal failure.

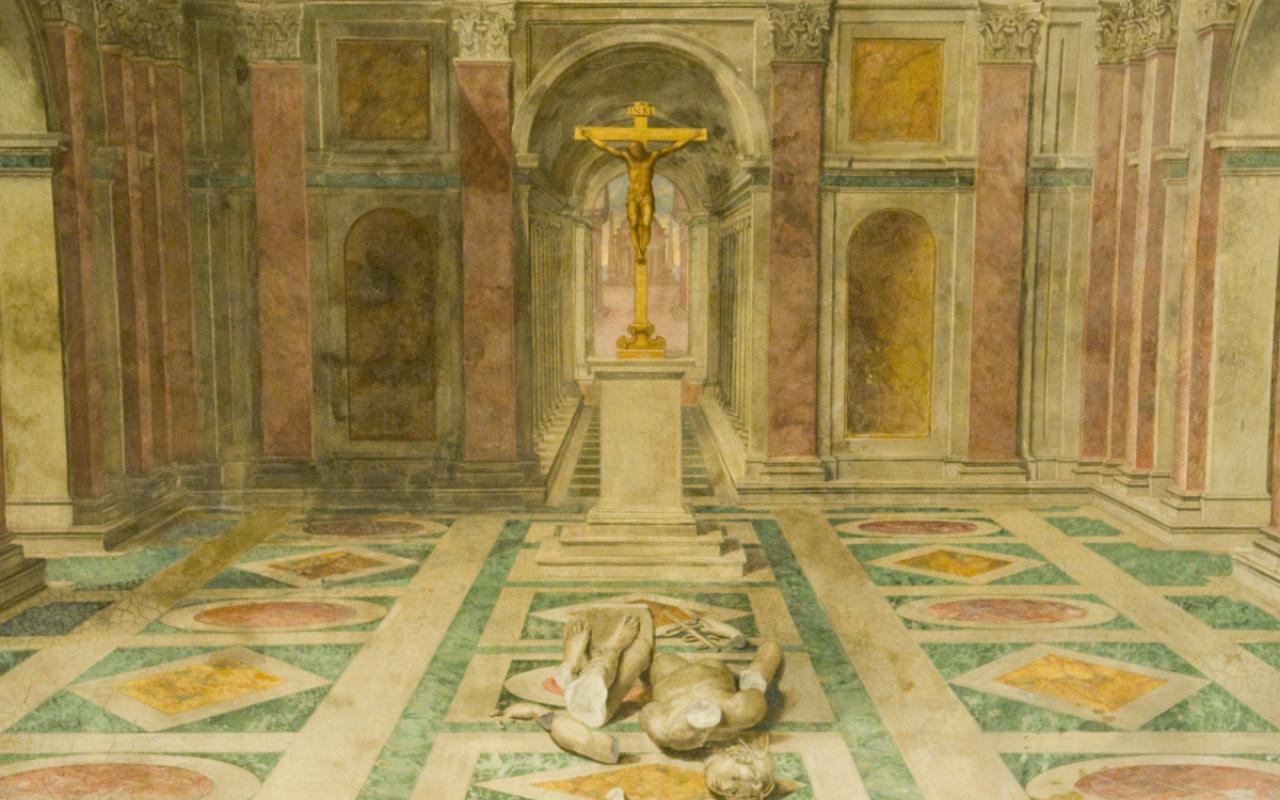

This is radically to misunderstand the point of Christ’s coming and the nature of the Christian Church. God did not visit the human race in Christ to fashion a perfect human society – not yet. The perfection for which we all long will certainly come, but not in this age of the world. Instead, God came among us to set up a kind of colony of heaven in the midst of a darkened world, a society of humans still fallen but on the road to their recovery that could act as a light and a leaven for those who were seeking their true home. The Church is a kind of resistance movement, set up under the reigning spiritual powers, an organized society “in the world but not of the world” through which Christ makes his appeal to generation after generation, setting them internally free from their oppression with the promise of full freedom when all things are restored. No one would fault the French Resistance during World War II for not being able to topple Nazi rule and transform France into a free society. That was not their task. They knew that an invasion was coming and that the dark powers that ruled their country would then be confronted in open battle. They dedicated themselves to making things as difficult for those powers as they could, ardently calling their fellow citizens back to their rightful allegiance in view of the coming invasion.

You will undergo many hardships, and the hardest of all will be to remember your true identity in the midst of a people who know nothing of our kingdom.

A fair assessment of Christianity will start by asking what the Church has always claimed to be doing, and then judge its success or failure on the basis of that purpose. It is a fair critique if an institution that understands itself as the “pillar and ground of truth” is found to be dealing in obvious falsehoods, or if a society that claims brotherly love as its special mark is found seriously lacking in care for others. It is not a fair critique of Christianity to claim that Christians have not perfected humanity or brought about a fully just society. They have never claimed to be able to do those things and they are sure that no one else will be able to accomplish them either, whatever their utopian dreams might be.

Due partly to the reasons given above, it is a simple fact that Christianity and the Church tend not to get a fair shake from the propaganda of this world. This is not something Christians should be particularly worried about. It was predicted by our Divine Master that his followers would regularly encounter hostility. Christians should do what they can to set the record straight, such that fair-minded people will have access to a more accurate account of history and honest inquirers will not held back by a false notion of the Church. Nevertheless, there are good reasons why their attempts seem to have little power to set the record straight.

Christ spoke of himself as a physician, and the Church has been understood as a kind of hospital for the morally and spiritually sick. The prevalence of sin in the Church is a sign not that the Church is a bad hospital or that Christ is an incompetent doctor, but only that we, the patients, are so often unwilling to follow the doctor’s orders. The proof of the Church’s healing power is seen in the lives of those who have listened to their divine physician, taken the medicine he has prescribed, and followed the protocols he has laid out: the saints. For those who seek God’s word in the Church’s Scriptures and who desire to be united with God in the Church’s sacramental life, Christ in the Church has never failed – not even once. While the human side of the Church is riddled with the weaknesses of humanity, the divine presence within the Church is a sure and unfailing road to the marvelous destiny intended for us beyond the confines of this age of the world.