Conversion of vision is no easy task: it requires a dual recognition of one's current vision and the greater vision to which one is called.

"In the course of history, this [the Church's apostolic] mission has taken on new forms and employed new strategies according to different places, situations, and historical periods. In our own time, it has been particularly challenged by an abandonment of the Faith - a phenomenon progressively more manifest in societies and cultures which for centuries seemed to be permeated by the Gospel. The social changes we have witnessed in recent decades have a long and complex history, and they have profoundly altered our way of looking at the world" (Pope Benedict XVI, Ubicumque et semper).

"Let us go forward in hope! A new millennium is opening before the Church like a vast ocean upon which we shall venture, relying on the help of Christ. The Son of God, who became incarnate two thousand years ago out of love for humanity, is at work even today: we need discerning eyes to see this and, above all, a generous heart to become the instruments of his work."

The main evangelistic task in an apostolic age, a task that also needs to be directed at many within the Church, is the presentation of the Gospel in such a way that the minds of its hearers can be given the opportunity to be transformed, converted from one way of looking at the world to a different way.

In a Christendom age, deeper conversion to Christ usually means taking more seriously the moral teaching of the Church. Most of those who live in such a time accept a host of dogmatic and overarching visionary truths: they believe there is a God, a heaven and a hell, a spiritual world of angelic and demonic beings, a judgment to come. They know, at a notional level, that this life is a preparation for another. These truths and this vision may be asleep in them, hardly influencing behavior, but they are still present. In such a context, when a person comes to deeper conversion and determines to pursue the Faith seriously, the result is seen mostly in the moral sphere: a readiness to keep the commandments and to do what is known to be right. In a Christendom time, much of preaching and teaching assumes the whole Christian narrative and centers its attention on emphasizing obedience to the Church’s moral precepts. This is natural enough, but it presents problems when the Christendom imaginative canopy is no longer in place. It can give rise to the view, often unconsciously assumed, that to be a Christian means to live a life of moral probity and nothing more. A comment like: “I know atheists who are more Christian than a lot of people at Church” is indicative of this attitude. The whole of the Christian faith tends to be reduced to following a specific moral order.

In an apostolic time, those who present the Gospel, whether to their parishes or to their families, should assume that the majority of their hearers are unconverted or half-converted in mind and imagination and have embraced to some degree the dominant non-Christian vision. The new evangelization aims at the renewal of the mind, because it recognizes that people’s minds have been barraged by a daily onslaught of false gospels, leading to confusion and distraction away from invisible realities to concerns solely of this world. Preaching in an apostolic age needs to begin with the appeal to a completely different way of seeing things; it needs to offer a different narrative concerning the great human drama; it needs to aim to put into place the key elements of the integrated Christian vision of the world within which the moral and spiritual disciplines the Church imposes find their place.

It is a strategic mistake to preach solely the moral vision of Christianity before the mind and overall vision have at least begun to be transformed. It is putting the cart before the horse. The reason so much of the Church’s moral teaching falls on deaf ears in our time is because it makes no sense according to the ruling vision of the society. As long as that vision holds sway in an individual mind, teaching about moral truth (except where Christian moral precepts line up with those of the ruling vision) will be ineffective and will produce either bewilderment or anger.

To take an example outside the strictly moral realm that still touches on it and elucidates a need of the time: it is often noted that a large percentage of Catholics in America do not believe in the doctrine of the Real Presence. They look at the Eucharist as symbolically and ritually meaningful but not as a transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. Some in the Church respond to this situation by saying that we need to be clearer about what the Church teaches; their view is that apparently many people do not know what that teaching is. While there may be simple ignorance of Church teaching in play here, a more significant factor is the lack of a sacramental vision of the world. Living in our culture and embracing its ruling vision, such Catholics have assumed as self-evident a materialistic, “scientific” view. If a thing looks like bread, tastes like bread, has the chemical composition of bread, then it is bread. A priest saying some prayers in the midst of a particular rite doesn’t change that. Likely enough, many Catholics who say they believe what the Church teaches about the Eucharist in fact don’t quite. They may acknowledge it out of a desire to be obedient, but it has no real meaning for them; they would not know how to go about defending it, and their conviction is fragile and easily lost.

The Miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming suddenly near to us from afar off, but upon our perceptions being made finer, so that for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always.

What is necessary here is a conversion of mind to a sacramental vision of the world. Not just at Mass, but all the time, we are living in a sacramental reality: we inhabit both a visible and an invisible world; we make our way through an intermingling of the seen and unseen such that what happens on the visible plane has implications in the vast invisible world. Our bodies are sacramental, a mingling of the spiritual and the material; the Catholic understanding of what and how we eat, what we do sexually, how we treat those who are sick or dead, are pointers toward the way the whole world works. Plunging a person into water really can, under the right circumstances, transfer an immortal soul from the kingdom of darkness to the kingdom of light. We walk in the presence of powerful invisible angelic beings not only when we might happen to think about them, but all the time. Touching another person involves two beings in spiritually meaningful contact. The world is an enchanted and dangerous and momentous place in which we are working out an incomprehensibly high destiny that transcends space and time. This view of the world is consonant with what natural sciences have discovered, but also goes beyond it. Once the realm beyond the natural world is seen and embraced, a whole set of doctrines becomes easier to understand and believe.

What is true of the Eucharist and the sacraments is true of much of Catholic practice in other areas, as well. Catholic teaching on sex makes sense when embedded in a Catholic vision; it makes little sense under the subjectivist naturalist default vision of the current culture and can even appear morally bad. Obligations to attend Mass, duties of faithfulness in a difficult marriage or of obedience to incompetent superiors, the meaning of suffering, the very existence of a saving doctrine that needs to be believed, come alive to the understanding only when they are perceived as the natural outworking of a cosmic reality. This means that the exposition of the Gospel, in preaching and teaching and liturgy and architecture and the arts, needs to accent this conversion of mind. There needs to be a counter-narrative to the overwhelming non-Christian narrative currently on offer. The Christian mythic vision (the true one) needs to be made available such that it can chase out the false myths of the day in the minds of believers and inquirers. Once this happens, questions of morality and Church discipline and articles of faith become easier to sort out. Until it happens, there will be half-conversion at best and a confused and often inadequate response to the Gospel. Such conversion of mind is especially needed in those who lead: in bishops and priests, parents and teachers, writers and scholars and artists. The great apostolic task of our time is to gain a genuine conversion of mind and vision.

If this is true, an obvious question arises: how do the current cultural vision and the Christian vision differ? What are their broad outlines? Adequately to answer that question would demand a far more thorough treatment than can be given here: the confusion of the modern mind makes difficult a neat summary of its sometimes self-contradictory and often fragmentary vision, and no one Christian can claim to have the definitive say on how the Christian vision should be articulated. But it may be of use to note, even if incompletely, some of the more obvious lines along which these mythic narrative understandings go forward. We will consider first the Christian way of seeing, and then we will sketch out the modern, progressive vision.

It should be noted that emphasizing the importance of the overall narrative and imaginative context of the Faith is not meant to suggest that careful theology, clear philosophy, detailed catechesis, and serious moral exertion are somehow unimportant. It is rather to say that all of these essential activities of the Church’s life will find their fullest expression and have their greatest effect when they are united in an integral view of the cosmos.

Concerning the Christian Way of Seeing

Christianity is the most shockingly momentous view of what it means to be human that has ever been seriously believed and pursued. The weight of this momentousness is both thrilling and terrifying. Much of the modern flight from Christianity, when it does not stem from boredom with a watered-down conventional version of the Faith, is precisely a flight from the seriousness of existence at the heart of the Christian vision, a refusal to attempt to scale the heights that all humans are called to in Christ.

In the Christian vision, to be a human is to be involved in an extraordinary adventure. The greatest adventure stories ever written are only echoes of it, pale shadows of what the lowliest human is in truth undergoing. This drama began before we were born and will continue after we die, and each of us has been given a unique role to play in it.

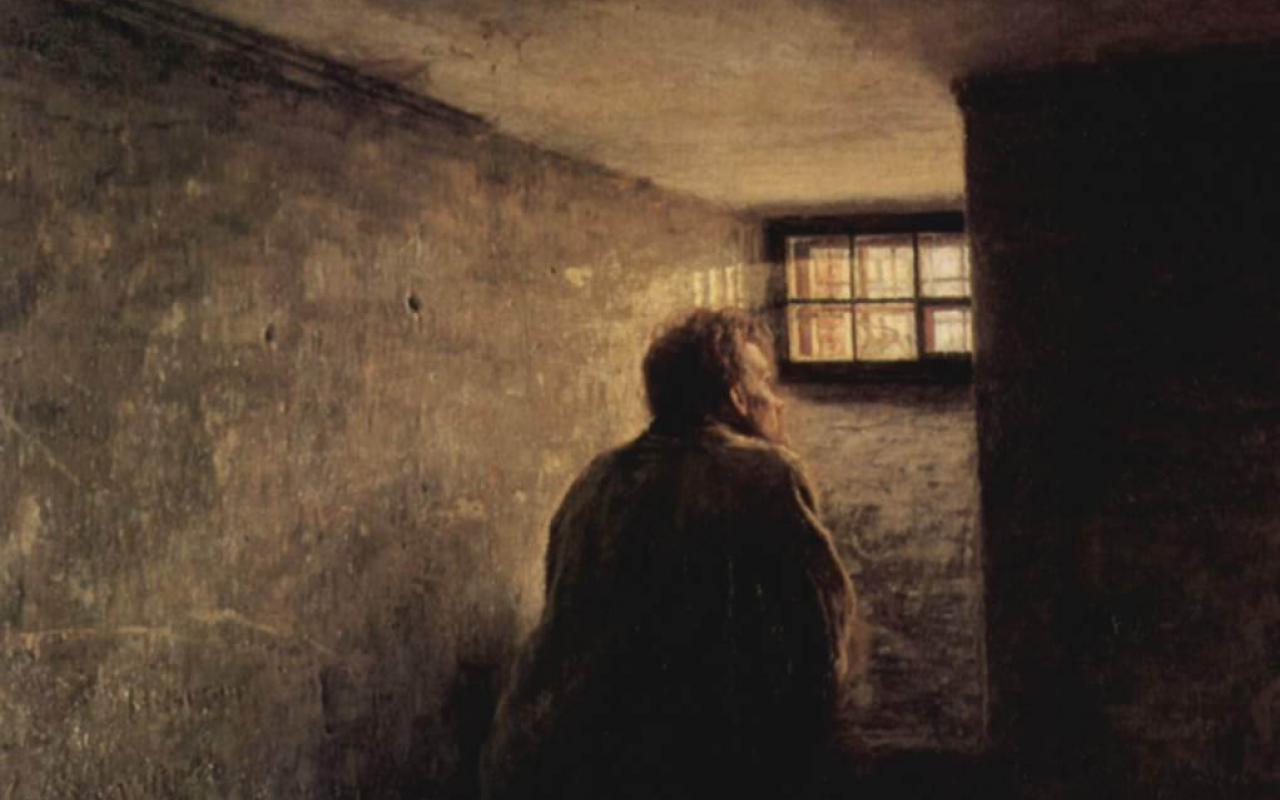

It is almost a definition of Christian conversion to call it the process by which a person comes alive to the invisible world in all its ramifications.

An integral aspect of this drama is that we have been born into an invisible world as well as a visible one, and the invisible world is incomparably more real, more lasting, more beautiful, and larger than the visible. Our blindness to that world represents much of our predicament. We are caught by the illusion of the merely seen and need to have our blindness cured. This drama involves us not only with the awful and marvelous and incomprehensible being of God, who created us with a decisive purpose in mind, but also with a cosmic struggle among creatures of spirit more powerful than we are, who influence human life for both good and evil. We have been born into a battle, and we are given the fearful and dignifying burden of choice: we need to take a side.

Every human has been created for a magnificent destiny that makes the greatest prizes of this world seem like uninteresting nothings, a destiny of such height that the imagination can hardly take it in. Not only are we meant to know good things, happiness, strength, length of existence, but we have been created to experience the unthinkable: to share in the very nature of God, to become – in the language so beloved by Eastern Christians – “divinized.” Created from the passing stuff of the material world fused with an invisible and immortal soul, we are each of us meant to be what we would be tempted to call gods: creatures of dazzling light and strength, beauty and goodness, sharing in and reflecting the power and beauty of the Infinite God.

Yet our destiny is at great risk. Had it not been for the intervention of God himself in our history by a shocking act of humility and love, our divine destiny would have been lost to us by our own pride and rebellion. Individually and as a race, we had sustained a mortal wound and forfeited our original purpose, becoming enslaved to evil spiritual creatures who themselves had turned their backs on the goodness and light of God and had become deformed and filled with malice.

The true history of the human race has been largely hidden; events of great significance take place away from the eyes of the world. By many orders of magnitude, the most important event in history was the coming of God himself among us in human form. He came not only to teach us truth but also to do battle for us against the powers of darkness, and having conquered them, to revivify us, individually and as a race. He gave his life as an offering to bring us back from the dead and to adopt us into his own divine nature. It was an event hardly noticed by the powerful and wealthy of the time; most knew nothing of it at all, and those who did treated it as of little importance. But that event has since come to echo through every corner of the world. This pattern continually repeats itself: the same hidden momentousness is true in the history of every individual. The real importance of a human life, not only in terms of its ultimate goal but also as regards its influence on current human affairs, is impossible to gauge by anything we can immediately see.

In coming to help and save humanity, God did not just intervene from outside. He conferred on us the high dignity of becoming one of us; he arranged matters such that a human might have the honor of conquering the enemies of humanity. He then established a society in the midst of a darkened world, a kind of colony of heaven that he inhabits and with which he clothes himself, and he gave to all who followed his lead a share in his own life, along with great responsibilities and notable powers to continue the work of saving and healing the human race. The fortunes of that society, and the ongoing story of God bringing humans from slavery to divinity, is the central drama of humanity, compared with which the rise and fall of whole nations and civilizations is of no lasting importance.

The current visible world will come to an end completely; the invisible world, of which each of us is part, will last forever. We are creatures on trial, given the opportunity by God’s mercy to work out our salvation, individually and communally, in “fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12). Our great task, the whole of our existence here, is to find and embrace our true destiny and to help others do the same by receiving and embracing the offer of mercy made to us. There are two and only two possible destinations for each human: to gain the life intended for us as members of a renewed humanity and offered to us through the God-made-man, or to turn obstinately from that life and end as immortal failures. For each human, both are real possibilities, and there is no evading the choice: we must seize either the one or the other.

Because we are not yet where we belong, not geographically and not in terms of our final creation, it follows that we cannot be fully happy during this life. We are creatures undergoing a testing of heart, awaiting our true home. When this visible world comes to an end and all is re-created, an event that may occur at any time, there will be a final assessment of the whole human race. All stories will be told truly, all secrets brought to light, all lies melted away. Christ will then determine who has responded to the free gift of forgiveness and so has been found worthy to “enter life,” to enjoy the kingdom of light and immortality. For those found worthy, all their piercing longings for perfection, for communion and love, for justice, for fulfillment, for beauty and goodness, will be triumphantly satisfied in a dance of joy and communion, and they will experience what they were created for.

This pattern continually repeats itself: the same hidden momentousness is true in the history of every individual. The real importance of a human life, not only in terms of its ultimate goal but also as regards its influence on current human affairs, is impossible to gauge by anything we can immediately see.

This very brief time that we are given to live on earth is thus at once both immensely significant and of little importance: unimportant in itself and significant in what it prepares us for. Christians hold matters of this world lightly and at the same time take them very seriously. They are not impressed by the scramble for money, fame, power, and pleasure so characteristic of our fallen race, knowing that such things have no ultimate significance. But they realize that in dealing with even the smallest details of life, they are working out an eternal destiny. They fight the darkness within themselves and embrace the life of love laid out for them by Christ, delighting in conforming their wills to his, knowing that obedience to him does not limit them or impede their self-development but rather brings them to their true selves, to freedom and fulfillment. They live as exiles, in hope and hard fighting, waiting for the final triumph of God, full of gratitude for what they have been given, full of hope for all they have been promised, full of love originating in Christ toward others who need to hear the good news of a merciful and forgiving and gift-giving God. They live in the visible world with the invisible always in view; they inhabit time in the constant recognition that they hover at the edge of eternity; they live in lowly disguise while waiting to be clothed with strength and immortality. They rise by falling and ascend the height of divinity by recognizing and repenting of their sins and willingly taking the lowest place with Christ. They fire their minds with the lives of the saints, those champions of faith in whom Christ and the new life he brings have been most influential. They battle for goodness and truth in order to gain a kingdom.

A life like this, characterized by the love of God and of others, lived as a member of the new humanity, no matter how troubled by suffering, no matter how obscure or difficult or filled with seeming failure, is a triumphant success that will end in a crown of blessedness and beauty. A life of great material success and fame and achievement but without love is a dismal failure that will end in darkness and eternal decay.

There is nothing in the above inadequate description of the Christian vision that claims any originality; others could no doubt give a better account. What is important for an apostolic age is its narrative and mythic character. Too often Christianity is presented to the mind of the modern believer or inquirer as a set of rules one follows, or as a number of unattached doctrinal statements one accepts, or as an organization one belongs to; but Christianity is not often enough presented as a way of seeing the whole of things. It can even appear that the rules and dogmas get in the way of human happiness. To be apostolic in vision (to repeat an earlier point) is to recognize that Christians don’t see some things differently than others: they see everything differently in the light of the extraordinary drama they have come to understand. To be apostolic is to do more than assent to a set of doctrinal truths or moral precepts, essential as they are; it is to experience daily the adventure that arises from the encounter with Christ; to view events and people moment by moment in the light of that vision; to be caught by the perilous and joy-filled work of learning to be transformed into divine beings headed for eternal rapture in the exhilarating embrace of God.

Concerning the Modern Progressive Way of Seeing

Since the dissolution of the Christendom vision, there is not any one single imaginative vision that has predominated in the Western mind; it is rather a chaos of confusing bits and pieces that do not easily fall together into a coherent whole. It is a blurred and often myopic way of seeing. Nonetheless, there are certain prevalent tropes that have come to undergird most of its variations. The point of naming these elements is not to examine them philosophically or critically; it is rather to identify the assumed first principles that give the vision its mythic potency. Modern progressives (which to some degree means nearly all of us) like to pride ourselves on our rational and scientific way of seeing things. But the power of the modern vision is not in its scientific accuracy. Its most captivating sources come not from reason and science but from romantic utopianism. Modern progressives are, as a group, remarkably impervious to genuine data. We first embrace theoretically conceived utopian ideals and then insist that the evidence fit our mythic visions, whether they be egalitarian, or feminist, or economic, or environmental, or sexual.

1. Faith in progress

The overarching narrative vision that first emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the West both borrowed from and contended against the Christendom vision out of which it arose. Among the most important of those borrowings was the belief that history was “going somewhere.” The Jewish view of history, embraced and expanded by Christians, had held that the whole of human history was a story with a beginning and an end: not sound and fury signifying nothing but a dramatic narrative whose author was God. According to that narrative, the human race was progressing not only through time but from lower to higher states: from nothingness to created beings, from fallen and mortally wounded creatures to sons and daughters of God filled with divine life, and ultimately, for those who gained the Kingdom, from flesh and blood to glorified spiritual embodiment and full participation in the divine. The whole of the Christian mind, taught by Christ, was thus oriented to the future. Along with the apostle Paul, Christians were forgetting what lay behind and were pressing on toward the upward call of God (Phillippians 3:14). At the hands of the Enlighteners, this heavenly vision was taken over and transformed into an earthly vision of perfection in space and time. What for the Christians could ultimately be accomplished only by God in a dramatic culmination that would signal the end of history was now to be accomplished by human effort alone within the confines of historical time. The perfection of the race was still in view; but the means, the conditions, the origin of that perfection had entirely changed. Visions of a humanity in perfect peace and contented prosperity, living by justice and practicing virtue, not in some distant “pie in the sky” world but here and now, danced before their eyes. This is why the modern vision can reasonably be termed “progressive.”

This progressive vision was more than just a hope of progress toward good things. It was faith in the ineluctable march of humanity on an ascent to an ever better and happier state of being. Greatly taken by the results of applied science in manipulating certain aspects of human life in a limited sphere and imaginatively captivated by theories of evolution, the modern mind came to believe that not only technologically (which made sense) but also socially and morally (which made no sense), the human race was on a necessary upward course. We came to think that we were superior to our ancestors, not just in rapidity of transportation or information flow, but in moral probity and wisdom about non-technological aspects of life – and this by the simple fact of being born later. Every dismissal of a particular moral stance or spiritual practice or time-honored bit of common sense with a phrase like “that’s so old fashioned” or “c’mon, it’s the twenty-first century” or “let’s be on the right side of history” signals the unnoticed assumption of the doctrine of progress. Without such an assumption, such phrases would be fatuously silly. But no one thinks them silly because the assumption of moral progress is so universal; it is one of the first principles of the modern mind.

Modern progressives are, as a group, remarkably impervious to genuine data. We first embrace theoretically conceived utopian ideals and then insist that the evidence fit our mythic visions, whether they be egalitarian, or feminist, or economic, or environmental, or sexual.

Bringing the hope of a perfected human society into historical time has a great deal of potency. But it brings also a new relationship to the world. Because the world is seen to be perfectible, and because we are the ones who need to accomplish that perfection, the progressive vision has given rise to a great impatience with imperfection of all kinds. It had long been a moral impetus in Christianity to be concerned for the suffering: to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, care for the sick, ease the burdens of old age. These were all aspects of the command to love one’s neighbor. In the Christian vision there had been no question of entirely solving the problems of poverty or sickness or aging outside the sovereign action of God; such conditions were part of the blight of fallen humanity – and only its most visible aspects. Worse than any of them was the state of sin and separation from God that impoverished the whole human race and of which all these physical manifestations were only the outward expression. One loved and helped those in need not because one was “fixing the world” but because they were God-created beings with a divine destiny, because in a special way they were sacramental representations of the poverty and hunger and sickness of everyone, and because to do so was to participate mystically in the self-forgetful charity of Christ working through his body.

In the modern progressive vision, concern for the poor and the sick has remained, but with a difference – one subtle enough in its first expressions but ultimately bearing serious consequences. Under the influence of a utopian vision of a society perfected by human energy, humble love for the poor was inevitably transposed into proud hatred for poverty; love for the sick became hatred for disease; love for the elderly turned into hatred for the ravages of age. The point was to arrive at a certain this-worldly state of physical and social health. What then was to be done if there were too many poor people to be reasonably enriched, or too many people with sicknesses that had no cure, or too many elderly people who were debilitated by effects of old age that could not be reversed or mitigated? By a perverse but necessary logic, the solution has been to eradicate the poor, eliminate the diseased, and euthanize the aged. According to the modern narrative the point is radically to solve the problems of humanity; suffering is therefore offensive and embarrassing and not to be endured. Pride, rather than love, is the root motivation.

When the broad lines of the progressive vision were first spelled out and preached, hopes were high for a radical transformation of the human race that would occur just around the corner. It was a new dawn, a re-creation of humanity, a break with the whole dark history of the race. There was a touching, if in retrospect remarkably naïve, confidence that evil could be overcome, justice established, vice conquered, and the human race brought to peace and goodness simply through the efforts of energetic people with the right ideas and the knowledge and skill to implement them. But the gospel of progress has not delivered on its promises, except in the one area of increasing human technological power and thereby of providing greater wealth and physical comfort. After the horrors of the twentieth century, to conclude that the human race is inevitably becoming morally better is to shut one’s eyes to mountains of evidence. The same lesson has been taught by the implementation of many plans and programs for social and moral betterment. The massive failure of the Soviet communist attempt to build a perfect society is only the most glaring example of failure across the board. Even when genuine good has been accomplished, it has fallen so far short of what was promised that the progressive gospel has become difficult wholeheartedly to believe by any except the young, who don’t yet have contrary experience and can be taken, for a time, by the heady wine of a Woodstock-like experience. These unfulfilled promises have left many of us in a precarious position. We often still speak the language of the progressive vision in politics and economics and social planning and academics; it is the only one on offer. But how many who are working in government or social services or the academy or business can believe the rhetoric? This explains the prevalence of a common type among us: the well-intentioned but disheartened and slightly cynical progressive. No longer quite believing that the world is undergoing a necessary transformation toward goodness, yet retaining a sentimental attachment to a lost youthful ideal and still wanting to do something positive along the way, the typical modern progressive has ceased dreaming great dreams and is mostly concerned to construct a meaningful and comfortable personal life, while still doing what might be possible to make at least some kind of difference in the world.

2. Denial of the Fall

An essential contour in the modern progressive vision is the denial of the Fall as part of the explanation for human evil. Christians had long taught that the human race was caught in a curse of its own making and that one of the key sources of the world’s evil was the wound in each of our hearts caused by pride and rejection of God. G. K. Chesterton once famously responded to a London newspaper’s request for essays on the question, “What’s wrong with the world?” with a two-word reply: “I am.” Chesterton meant that for the Christian, the first and most important task in making the world a better place is to be attentive to one’s own conversion. The progressive vision, by contrast, while aware of evil in the world, finds the source of that evil elsewhere: it is not the result of an internal wound in each human, but the bad fruit of ignorance, whether of physical laws or social structures or psychological principles. There is no need to engage in the humiliating and continuing battle to forge a new heart within; evil could be undone and goodness established by gaining and applying the requisite knowledge.

Having discounted the evil in each human heart and having little time for the idea of personal evil in fallen angelic beings, the progressive vision still needed to identify a source for the prevalence of active evil in the world. That source has always been found in a particular group of people who have been deemed to stand athwart the march of human progress. It might be the aristocracy, or the Jews, or the bourgeoisie, or the Catholics, or the homophobes, or the breeders, or the reactionaries, or the whoever. Over against them were the pure, the enlightened ones, those “on the right side of history.” Having relegated demons to the nursery, every utopian progressive vision finds itself constrained to demonize some portion of fellow humans. This has led to great injustice and at times to some of the most barbaric treatment of humans in history; but it is not seen that way by those under the influence of the progressive myth. According to the Christian vision it was the devil alone who was to be opposed with a perfect hatred; fellow humans were to be treated with respect, and even enemies, shockingly, with love. That at least was the ideal. Under the progressive vision, it became proper to hate certain other humans with the perfect hatred once reserved for the devil. Such an attitude, expressing itself in events like the Reign of Terror, the Gulag, the Holocaust, and the abortion mills, has been justified by the concern to bring about the promise of perfection granted by the progressive vision. Thus, the denial of the Fall inevitably brings with it a culture of death, not because its proponents set out to kill, but because the utopian ideal runs up against a fatally flawed humanity. The only options are either to eradicate those whose perceived weakness or evil keep the dream of the new humanity from being realized or to give up the project altogether.

3. Marginalization of God

In its manifold forms, the modern narrative myth is constant in this: it marginalizes God as an actor in human history. Sometimes this is expressed in an explicitly atheistic narrative, but often it is not. Most commonly, the modern vision does not say “God does not exist,” but rather, “God does not matter,” which comes, practically speaking, to the same thing. Under the modern progressive vision, one can reasonably attempt to make sense of one’s life, sort out one’s friends, pursue one’s love affairs, decide on questions of marriage and family, arrange a career, order the affairs of government, establish and maintain justice, handle geopolitical relations, determine what is right and wrong, all without recourse to the divine, without consulting the creator of all who “upholds the universe by his word of power” (Hebrews 1:3). The modern vision involves what might be called practical atheism, whatever the personal belief of many of its possessors might be.

G. K. Chesterton once famously responded to a London newspaper’s request for essays on the question, “What’s wrong with the world?” with a two-word reply: “I am.” Chesterton meant that for the Christian, the first and most important task in making the world a better place is to be attentive to one’s own conversion.

Hence, under the modern progressive vision, religion is instinctively held to be so very private a matter. Americans like to be religious, but we also like to customize our religions to our personal preferences. We are not interested in religion as an account of reality; it is rather something that enhances our experience and helps us deal with the stress of existence. We are not so much seeking a Lord as looking for a therapist. “Whatever works for you” is a reasonable dictum under such an understanding. Should a given religion become a source of friction because its adherents claim it to be an account of universal truth, it provokes immediate hostility. It is no surprise that a historically irresponsible statement like “religions have been the greatest cause of wars in history” can be taken seriously by modern progressives. Its acceptability is not due to its accuracy but to the way it conforms to and supports the progressive myth.

There is an unfortunate by-product that comes from marginalizing God: one wakes to find the universe a boring place. God is the one supremely interesting personality, and a world that banishes him also banishes its only genuine source of animation and interest. This explains something of the massive boredom of the modern age. Because we have no engrossing and abiding interest that engages the whole of our minds and personalities, we need to be constantly titillated and distracted. When seen as reflections of the infinite creativity of God swept up in a momentous drama, all things, even the least significant, hold interest. When God is absent, nothing – not art nor politics nor sports nor sex nor the pursuit of money nor even “the most interesting man in the world” – can keep boredom and disillusion at bay for long.

4. Intoxication with the world of space and time

It is almost a definition of Christian conversion to call it the process by which a person comes alive to the invisible world in all its ramifications. “We look not to the things that are seen,” says Saint Paul, “but to the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal” (2 Corinthians 4:18). This is a restatement of Jesus’ teaching about laying up treasure in heaven where there is no rust, and no thieves, and no moths (cf. Mathew 6). The unseen but real – God, angelic beings, human souls, the heavenly throne room – holds first place in the Christian vision as being of primary importance. Things that are seen take on importance only as they reveal and open up the unseen world that interpenetrates and upholds them. This is the meaning of sacramentality. The modern progressive vision is almost the antithesis of sacramentality. Under the modern vision, we look constantly, eagerly, incessantly, with anxiety and hope and longing to the things that are seen. Whether we hold, theoretically, that there are unseen things as well hardly matters. We are distracted and delighted and dismayed by the things of time and sense, and we attempt to make our lives meaningful according to their logic alone.

In the modern progressive vision, it becomes natural to consider human relations and the entire structure of daily life in political terms. We think that world peace and social contentment can be achieved if only we erect the proper political structures and set up the right programs. When a problem arises we look for a political solution; we attempt to handle complex human matters by establishing policies and protocols; we live by publicity and polls; we think we are in touch with “the way things are” if we watch a lot of news programs.

Under this vision it is natural that we spend so many billions of dollars on health care and that doctors and psychologists reign as high priests of the culture. It is natural that we think economic prosperity the beginning and end of human success and consider those who are not prosperous as marginalized and oppressed. It is natural that we are offended by suffering and do everything in our power to maximize our comfort, even to the point of insisting on a comfortable death. It is natural that we think the most important questions facing us have to do with the planet and its viability. It is natural that we are obsessed with physical appearance and the luxurious trappings of success. It is natural that we carefully calculate whether and how many and what type of children we would like to have according to an equation of immediate enjoyment and often determine to have no children at all or do away with the ones we have ‘accidentally’ conceived, since they are prohibitively expensive and a great deal of trouble. It is natural that we hold to a narrative of success limited by the date of our birth and the date of our death, one that carries with it pictures of interesting friends, fulfilling careers, dynamic and meaningful sexual relationships, fun and adventurous experiences, and a golden old age.

Noteworthy in the progressive vision is the loss of the momentous: the disappearance of a final judgment, the lack of a sense that humans are undergoing a sifting and a testing that will have hugely practical consequences beyond this life. The progressive vision allows for no hell, and while most still think of or hope for a heaven, they do so in a vague and misty way. The only meaningful criteria for judging success or failure are those that can be seen: popularity, power, wealth, comfort, and personal enrichment.

And because we are actually immortal souls created to dance with the living God, called to an eternal destiny that won’t stop haunting us, it is natural under such a vision of smallness that we fall into creeping despair and attempt to medicate our misery by taking huge doses of the true opiate of the masses – electronic entertainment.

5. Freedom to choose as the essence of human dignity and the source of human happiness

In the modern progressive vision, ‘freedom’ is an incantatory idea. The modern narrative is a story of liberation from oppressive forces. To maximize human freedom is seen as a self-evident moral task and a self-evident source of human happiness and human dignity. Despite the complexity of what the word ‘freedom’ might mean, what it has and hasn’t meant at different times, what are the many and often hard-to-establish conditions for its promotion, how many difficult questions there are to be unraveled in a simple phrase such as “humans are meant for freedom,” nonetheless in the progressive lexicon freedom is an unproblematic word denoting a simple idea. Let any cause, any program, any activity, any person, be claimed to promote freedom, and it is assumed that we are dealing with a simple good. Let something be thought to get in the way of freedom, and it is clear that it must be swept away. Much of the mythic power of the progressive vision comes from its claim to champion freedom and, by that means, to provide ever-increasing dignity to humans.

Freedom is a concept and an ideal that has been at the heart of western civilization from its origin among the Greeks and its penetration by Christianity. The whole of the Christian hope has been summed up by saying that, in Christ, the human is set free: from death, from devilish tyranny, from destructive passions, from ignorance, brought to the status of sons and daughters of God as free men and women. To be a free human was the highest goal of the civilization; the traditional education in the liberal arts was geared to help achieve this aim. Involved in this classical and Christian understanding of freedom was the idea that we were most free when we became most fully what we were meant to be, when we approximated most truly our given nature. To become free under the Christian mythic vision was therefore to grow into a particular image, one given us by the God who had created us and according to which we would find happiness and goodness. Freedom was thus not an arbitrary concept, but rather a task with a goal. The accomplishment of freedom always demanded serious discipline according to what was good and true and right.

To become free under the Christian mythic vision was therefore to grow into a particular image, one given us by the God who had created us and according to which we would find happiness and goodness. Freedom was thus not an arbitrary concept, but rather a task with a goal.

In the progressive vision, freedom has come to mean something different: the possibility of choosing whatever my individual will desires at whatever time. I am most free when there is nothing impeding me from doing what I wish to do, and I will be most happy and most fully human and dignified when I am most free to choose my own will. What is right and wrong and how I conceive my own existence is my own choice. To be autonomous (a law unto oneself) is the greatest good. The most dignified person is the one who has self-identified, who has determined who and what he or she (interchangeably) will or will not be.

Such a view inevitably, if unwittingly, makes God into the great enemy of humanity. If there is a moral and spiritual order that originates outside of myself, if there is an intention in my creation and a nature given to me, then I am not absolutely free to be my own creator, and my autonomy is at risk. To protect this autonomy, God is always put at the margins of the modern myth. If he exists at all, he is a vague and misty principle that allows for almost infinite malleability, a kind of miasma of spirituality that will allow me to construct my own sense of self and of the world around me.

The insistence on autonomy in the progressive vision has induced an intoxication with breaking things that are thought to stand in the way of personal freedom. Freedom is to be accomplished not in the careful construction over time of the conditions under which humans could have the opportunity to achieve their true nature, but rather in the bursting of bonds that hold the individual will in check. Under this vision, revolution gains a kind of moral magic as the privileged instrument of freedom, and the tearing down of Bastilles, whether they come in the form of moral norms or social conventions or religious traditions or oppressive governments, is the self-evident task of serious people. This explains something of the strange barbarity of so much of modernity. Despite its sophistication, its gilded rhetoric and high hopes for good things, it has a destructive core. It promises a social and personal paradise, but saddled with a false understanding of humanity and its ills and thinking that the desired utopia will arrive as a matter of course once the requisite restraints have been demolished, it too often leaves behind not a lush garden but a howling wasteland.

6. Consumer contentment as the default experience

For all the grand utopian elements in the progressive vision, for all its impressive narrative power, in practice it provides little for the individual person to live by from day to day. After all, we each inhabit a universe of our own, and we need to have aspirations and ideals for our personal world. High sounding phrases like “making the world a better place” and “helping the future of humanity” and “fighting for hope and change” are too vague in meaning and too loose in accomplishment to sustain us. We need a narrative closer to home; we need to know that each of us is walking a daily path leading to personal fulfillment, and here the progressive utopian vision provides little to nourish us. As a result, the default vision that many live under is one of consumer contentment. We exercise freedom by buying what we want; we find meaning by keeping abreast of the “next big thing”; we make the world a better place by carefully constructing a personal statement of existence whose brand is produced out of the consumer choices we make. Ironically, the stirring proclamation of the progressive gospel to remake and perfect the human race by banishing God and seizing our personal destiny in our own hands winds up for most of us in online buying or in a shopping mall. “We have nothing to lose but our chains!” has devolved into “Shop till you drop!”

The modern progressive vision is all around us, incessantly hammered home with all the pervasive power of electronic imagery and consumer affluence, but compared to the one given us by God, it is a weak and anemic vision. From its beginnings its claims have been unreal, and it has been so weakened by generations of dismal human experience that it can now be sustained only by economic prosperity and the apparent lack of a good alternative. The hope that mankind would be made better has in practice been replaced by the hope that we can build yet faster and more powerful phones and screens; the dreams of a perfected world of justice and freedom are ebbing into vague hopes of biotechnological enhancement of physical powers. Much of the current strength of the modern vision is in its immediacy: it appeals with great skill to the human propensity to be distracted by the sensual and the seen. But it offers little of substance to the deepest aspects of the human person: it is intellectually bankrupt and spiritually impoverished. It should not therefore be a source of intimidation or anxiety for Christians, who have a much more compelling way to understand the world and a much richer life to experience and to offer our fellow pilgrims in this world. It is not coincidental that so much of the entertainment eagerly pursued by the young minds among us involves epic dramas, cosmic battles among powerful spiritual forces for good and evil that demand of the young hero or heroine extraordinary character, commitment and sacrifice for the saving of the world. What the progressive vision tossed out the door has snuck back, in mutilated form, through the window. This should not surprise us: those who have been deprived of the real thing will grope after pale substitutes.

The Holy Spirit is at work in every age, ours included. If it is true, as we are assured by Saint Paul, that grace is more present the more that evil abounds (cf. Romans 5), we might expect an especially abundant action of the Holy Spirit in our own time. Our task is to understand the age we have been given, to trace out how the Holy Spirit is working in it, and to seize the adventure of cooperating with him. May we be given the wisdom and the courage to rise to the challenge of the new apostolic age that is coming upon us and to prove faithful stewards in our generation of the saving message and liberating life given us by Jesus Christ.

This five-part series is drawn from From Christendom to Apostolic Mission: Pastoral Strategies for an Apostolic Age, published by the University of Mary (2020).