Historian Christopher Dawson recognized within the life of the Church six distinct "Ages," each possessed of a unique origin, distinctive achievements, and Age-ending crisis.

The typical schema for ordering Church history follows the tripartite division established by Enlightenment historians: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. While there are reasons for such a division, it arises partly from the use of an interpretive lens that has viewed Christianity as an unfortunate lapse from high civilization into barbarity and superstition. The implicit narrative offered by this way of ordering the past went like this: The ancient world of Greece and Rome had achieved a high level of human accomplishment that was then submerged under the influence of Christianity. The Renaissance – the rebirth of the classical – began the restoration of what had been lost, followed by the Enlightenment, which turned a bright beam on the dark shadows of superstition and opened up vistas of unlimited progress for the future. The thousand-year stretch between the fall of Rome and the Italian Renaissance was thus classed as the "middle" ages, an extended hiccup that did not warrant its own name and did not deserve much serious consideration.

The more obvious biases of such a way of looking at history have long been undermined by serious historical work; nevertheless, the distortion often lingers in the modern imagination. The word "medieval" continues to be used as an adjective meaning barbarous, cruel, and oppressive. It could be asked why, given so much historical evidence to the contrary, erroneous (and frankly silly) views of the Medieval period persist in the modern imagination. The answer has much to do with the need to protect the modern myth of progress. Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment believers in progress have an understandable concern to portray the world that preceded them in the darkest possible colors as a foil for their progressive programs. The result has been a serious misrepresentation of Western history, especially as regards the Medieval period. An age characterized by the application of reason to all areas of life has thus been caricatured as anti-rational and fanatical. A time when political power was not highly concentrated and there were no prisons, few standing armies, and by necessity a good measure of local freedoms, has been deplored as an age of political tyranny and oppression (examples of which could be found much more amply in both ancient and modern times). A period that was highly creative in social institutions and scientific exploration has been written off as the "dark ages."

The noted historian Christopher Dawson has provided a more nuanced and less trenchantly skewed historical scheme. Dawson does not rewrite the entire narrative; in fact, he gives due importance to the genuine historical developments that lay behind the Enlightenment ordering scheme. However, he is alive to the complexity of cultural transformation, and he is aware of the extraordinary nature of the Christian Church as a social and cultural institution. Dawson pays attention to the differing ways the Church has interacted with and adapted to the cultures it has inhabited. For these reasons, Dawson's way of mapping the history of the Western Church can provide a more useful and less distorting lens for understanding the West's cultural and historical development.

Religion is not so much one among many social and moral factors; rather, it is instead the atmosphere that suffuses the whole life of the culture, the lens by which everything is perceived. The idea that a given culture's religion could ever simply be private and personal is foreign to this conception.

Dawson's scheme embodies a principle present in all of his historical work: namely, that amid the many and complex factors that go into understanding a given society or civilization, the most important among them for determining the character of the culture is that society's religion. In Dawson's understanding, a society's religion is the moral and spiritual vision around which the whole common life of the culture is organized. Religion is not so much one among many social and moral factors; rather, it is instead the atmosphere that suffuses the whole life of the culture, the lens by which everything is perceived. The idea that a given culture's religion could ever simply be private and personal is foreign to this conception. If a particular religious expression loses its ability to hold a society together, that society will enter into crisis unless or until another religion can be found to supplant it.

Dawson sees six "Ages" of the Church in the West, six connected but discrete periods of cultural adaptation made by the Church to the wider culture. The six Ages have much in common with one another, stemming from the continuities inherent in the culture and in the Christian faith. Within that continuous cultural narrative, however, each Age represents a unique relationship between Christianity and the wider culture, and each possesses an internal coherence of its own.

Dawson goes yet a step further and sees an inner dynamic within each of the six Ages, a fundamental pattern of cultural engagement that, broadly speaking, follows a three-phase process. The first phase in each Age is characterized by a burst of creative spiritual and cultural activity in the face of a crisis of some kind that has overthrown earlier modes of social and spiritual order into confusion. That cultural effusion leads to the second phase, during which the Church penetrates the wider culture more deeply, arriving at a kind of cultural equilibrium. As human cultures are dynamic rather than static, however, a new set of challenges arises that brings about the third phase, in which the achieved cultural order is undermined or overthrown, and a tendency toward cultural and spiritual chaos reigns. The crisis and retreat that ends each Age provides the challenge that sparks new initiatives in the next Age, serving as the soil from which new creative energies spring. The picture that emerges is that of a highly dynamic and energetic Church institution that finds a way to pursue its mission in whatever cultural soil it inhabits, adapting and influencing the culture in impressive ways while never simply becoming coterminous with it.

What follows below is a brief outline of Dawson's historical scheme. The outline given here notes each of the six Ages and gives a brief description of the three phases of development within each. It also includes notes on distinctive markers of each Age: the main locus of spiritual advance, some of the Age's representative saints, and decisive Church councils at which much of the cultural and spiritual accomplishment of the Age was codified. The outline is only a kind of snapshot showing the main lines along which the Church was incarnating the life of Christ anew in each successive cultural period. It is meant as a road map, and, as must be obvious in a scheme that covers 2,000 years in roughly half as many words, does not claim to provide anything like a comprehensive account of the life of the Church. Serious investigators will want to dive much more deeply into the intricacies of each age – but a map is a handy tool for those who do not want to get lost along the way.

Before examining the outline below, it will be worthwhile to consider some of Dawson's own comments on the matter:

First Age: The Apostolic Age

from Christ's birth to c. AD 300

- This age was unique in that it was the unrepeatable beginning of everything else: the death and resurrection of Christ, the sending of the Holy Spirit, and the founding of the Church.

Distinctive achievement:

- Distinctive achievements of this age included the growth of the Church, the writing of the Scriptures, the missionary penetration of the Greco-Roman world and beyond with Christian churches in all major cities, the preliminary defense of the faith in the midst of a pagan society, and the beginnings of Christian art and literature.

Characteristic forms of Church Life:

- Characteristic forms of Church life included urban Christian communities, Apostles, evangelists, martyrs and confessors, apologists.

Key Saints:

- Our Lady, Peter, Paul, John, James, and the rest of the Apostles, Clement, Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Cyprian, Agnes, Cecilia, Catherine of Alexandria

Councils:

- the Council of Jerusalem (AD 49)

Crisis and Retreat:

- The great crisis of this age was the attempt to destroy the Church systematically in the Great Persecution of Diocletian (AD 280-300).

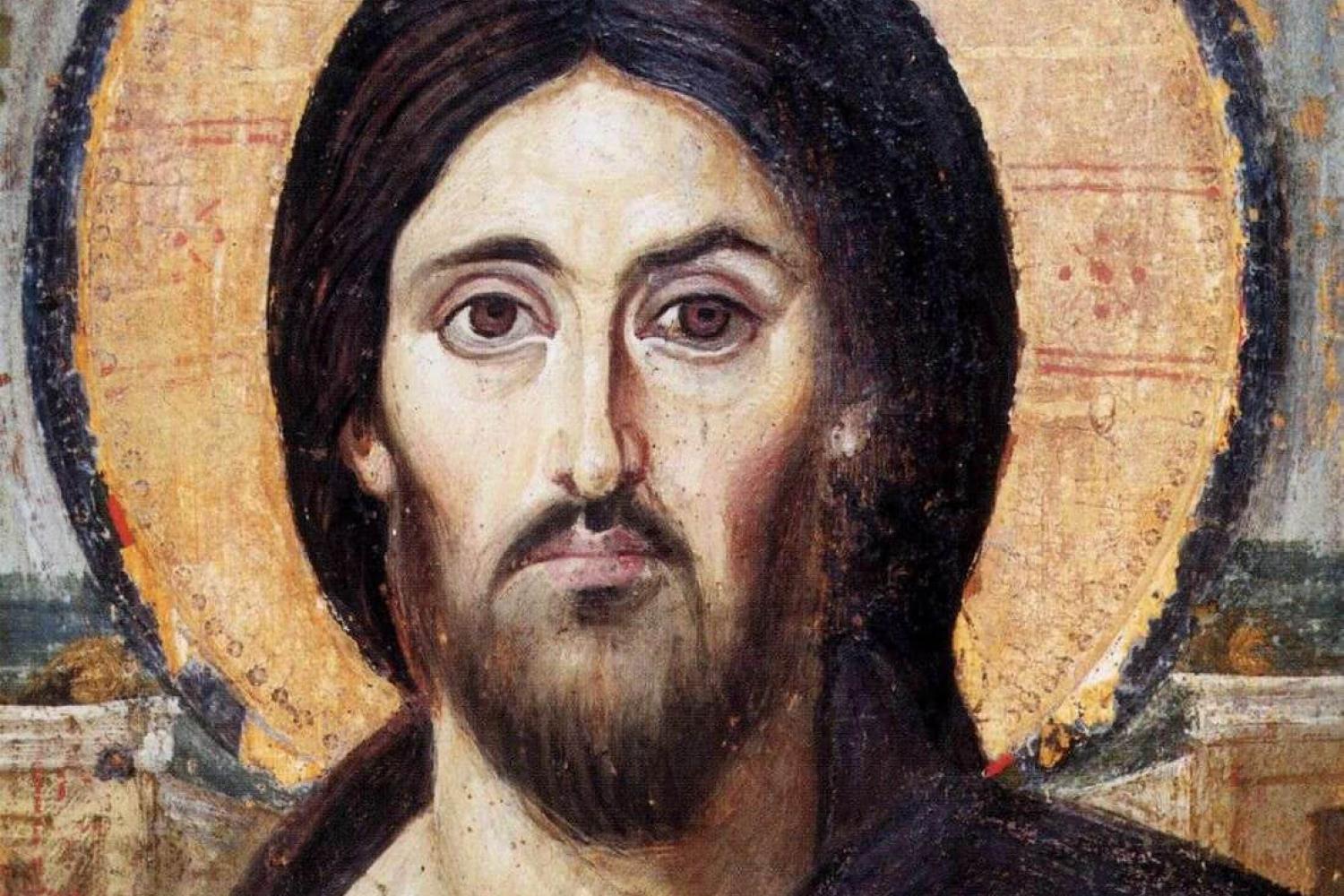

Second Age: The Patristic Age

c. AD 300 to c. AD 650

- This age opened with the triumph of Constantine and the first foundations of a Christian society following its legalization (AD 313) and eventual elevation as the official religion of the Roman Empire by Theodosius (AD 380). The fourth century served as a classical age of the Church Fathers.

Distinctive achievement:

- Distinctive achievements of this age included the theological and cultural work of the Church Fathers, who accomplished the clarification of Christian belief and the fusion of Christian and Greek ideals; the grounding of a deeply Christian society, e.g., the great Basilicas and Code of Justinian; the development of a distinctive Christian art.

Characteristic forms of Church Life:

- Characteristic forms of Church life in this age included the rise of early monasticism and the theologian bishops.

Key Saints:

- Anthony of the Desert, Ambrose, Macrina, Gregory Nazianzen, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, John Chrysostom, Athanasius, Paula, Jerome, Augustine, Monica, Leo the Great, Benedict, Scholastica

Councils:

- the Christological Councils: Nicaea (AD 325), Constantinople (AD 381), Ephesus (AD 431), and Chalcedon (AD 451)

Crises and Retreat:

- The great crises of this age were the loss of Christian unity due to the Nestorian and Eutychian heresies and the loss of much of the Church's heartland, including three of the five Patriarchs, to Arab Muslim invaders (AD 620-650).

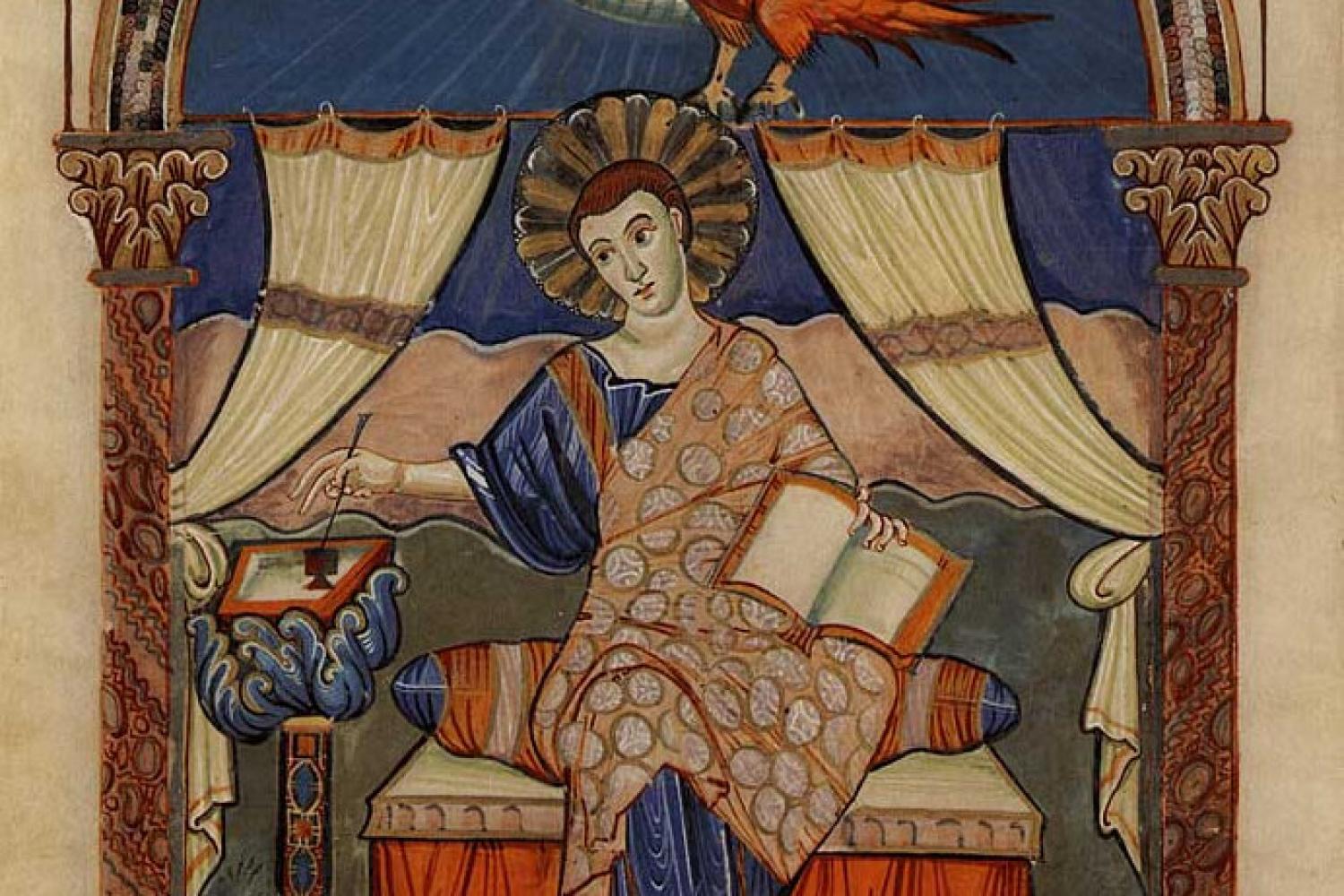

Third Age: The Carolingian Age

c. AD 650 to c. AD 1000

- This age opens due in large part to the missionary conversion of Germanic peoples – the Franks, Goths, Lombards, and Anglo-Saxons – accomplished largely by monks.

Distinctive achievement:

- Distinctive achievements of this age included recovery from the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the founding of the Holy Roman Empire with the crowning of Charlemagne (AD 800), and the rise of monasticism as a significant cultural influence.

Characteristic forms of Church Life:

- Characteristic forms of Church life in this age were Christian kingdoms and Benedictine monasteries.

Key Saints:

- Patrick, Augustine of Canterbury, Columba, Boniface, Bede the Venerable, Frideswide

Crises and Retreat:

- The great crises of this age were the collapse of the Carolingian Empire (tenth century) under renewed onslaughts from the north (Vikings), the east (Hungarians), and the south (Saracens), as well as an increasing worldliness in the Christian world as Church and monastic offices were increasingly dominated by local lords.

Fourth Age: The High Middle Ages

c. AD 1000 to c. AD 1500

- This age opened with the Cluniac reforms, which rejuvenated the monastic ideal, as well as the reforms of Gregory VII, which revitalized the papacy.

Distinctive achievement:

- Distinctive achievements of this age included medieval Christendom at the height of its international cohesion under the papacy, Romanesque and Gothic architecture, and the deeper conversion of the growing cities by the mendicant orders.

Characteristic forms of Church Life:

- Characteristic forms of Church life in this age included the rise of universities, the Cluniac and Cistercian monastic orders, and the mendicant orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, and Augustinians).

Key Saints:

- Gregory VII, Anselm, Hugh of Cluny, Bernard of Clairvaux, Francis, Clare, Dominic, Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, Anthony of Padua, Catherine of Siena, Bridget of Sweden

Councils:

- the four Lateran Councils (AD 1139-1215)

Crises and Retreat:

- The great crises of this age were the Papal Schism at the end of the fourteenth century, the fragmentation of Europe, the increasing secularization of the papacy, and the Reformation (which began in AD 1517).

Fifth Age: The Age of the Baroque

c. AD 1500 to c. AD 1750

- This age opened with the Catholic Reformation at the hands of reforming religious orders and a revitalization of the papacy that brought about the Council of Trent.

Distinctive achievement:

- Distinctive achievements of this age included the integration of Catholic spiritual reform with Renaissance classical culture in the Baroque, France's "Splendid Century," the development of Catholic mysticism, and international missionary activity in newly discovered lands at the hands of religious orders.

Characteristic forms of Church Life:

- Characteristic forms of Church life in this age included the Apostolic Societies: the Jesuits, Ursulines, Theatines, Barnabites, and Oratorians.

Key Saints:

- Ignatius of Loyola, Francis Xavier, Angela Merici, Charles Borromeo, Teresa of Avila, Philip Neri, Pope Pius V, Francis de Sales, Vincent de Paul, Margaret Mary

Councils:

- the Council of Trent (AD 1545-1563)

Crises and Retreat:

- The great crises of this age were the Enlightenment and the secularization of Europe's elites, as well as the French Revolution.

Sixth Age: The Modern Age

c. AD 1750 to the present

- This age is unique in that we are in the midst of it, and it is not clear where we currently stand in regard to the three phases of cultural interaction; thus, the suggestions here are tentative.

Distinctive achievement:

- Unknown: it is still too early to say.

Characteristic forms of Church Life:

- Characteristic forms of Church life in this age seem to include ecclesiastic movements of spiritual renewal: Opus Dei, Focolare, Communion and Liberation, the Neo-Catechumanl Way, the Charismatic Renewal, etc.

Key Saints:

- John Vianney, Don Bosco, John Henry Newman, Therese of Lisieux, Maximillian Kolbe, Mother Teresa, Padre Pio, Pope John Paul II

Councils:

- the Vatican Councils (AD 1870, AD 1962-1965)

1 Christopher Dawson, “The Six Ages of the Church,” in Christianity and European Culture: Selections from the Work of Christopher Dawson, ed. Gerald J. Russello (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 1998), 44-45.

2 Ibid., 44.

3 Ibid., 35.

4 Ibid., 45.

Further Reading

- Christopher Dawson, “The Six Ages of the Church,” in Christianity and European Culture (edited by Gerald J. Russello)

- Remi Brague, Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization

- Christopher Dawson, Religion and the Rise of Western Culture