Last week, The Atlantic published a piece entitled “End the phone-based childhood now.” It’s a sentiment that, at this point, probably few people would disagree with, even as our culture also seems hamstrung in doing anything about it.

But the author, Jonathan Haidt, has more to say than his use of the eye-catching term “phone-based” at first suggests. Naturally, that adjective carries with it the specter of statistics a lot of us know well, hearing them bleakly repeated, in study after study, year after year: the astonishing increase in mental health conditions among teens over the past decade or so, their reduced capacity to maintain relationships and flourish in social settings, their aversion to independence and even mildly ambitious ventures.

Instead Haidt also takes a step back, probing not only the tag “phone-based” but a more fundamental question: “What is childhood – including adolescence?”

Haidt argues that the harm being done to young people by smartphones and social media is not only a function of the devices in their hands. The problem is also that they are coming of age in a culture that has grown inept in knowing how to bring people to maturity. Children don’t wander unsupervised to the local park (or even to their own backyards), for instance, dissolving contexts in which what used to happen in childhood happened. There are fewer settings in which they find themselves increasingly responsible for resolving conflict, for example; where they have to gauge physical, social, and emotional risk; and where they are responsible for solving problems with a limited, initially low-stakes scope. They are, some might say, “over-protected” in their real, non-digital lives.

But they aren’t protected in their lives online. There, social blunders are broadcasted to a massive audience, such that much of their risk-taking becomes much riskier than a young person’s development is ready for. By the same token, they’re also put under no pressure to navigate all the ups and downs of real-life friendships. They simply “block” the friends they don’t want anymore and flip through the seemingly infinite number of profiles they can engage instead, catching them in a repeating cycle of effortless but also meaningless relationships.

The result is that they are no longer being ushered into a fitting sense of responsibility for themselves, or for one another, as they grow up, and instead they are plunged into “a confusing, placeless, ahistorical maelstrom” where expectations of them are both too much and too little. No thirteen-year-old should be able to curate an amenable and attractive sense of self for thousands of people; he or she should, though, be able to make a best friend, and to have long, regular conversations with them.

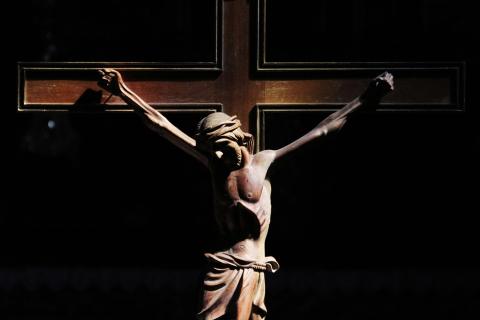

Thus Haidt’s plea to “end the phone-based childhood now” could be preceded by another plea: let’s also end the never-beginning, never-ending, nebulous childhood now. It wasn’t so long ago that most human societies thought it so vital to define when one had come of age that they had rites of passage to mark the transition out of childhood and into adulthood, at which point a new adult would dress differently, or get invited to different events and settings, or even be spoken to with a different name. We are very far adrift from those kinds of rituals. However, we’re also not simply victims of our contexts, as Haidt finishes off his article by reminding us. We can choose to claim responsibility for ourselves, our families, our friends; to advocate for phone-free settings where social risks aren’t quite so risky but shrugging off relational responsibility is; and to unplug, ourselves, in order to engage more of “real life,” with its real life joys and real life trials that both promise to give us back to ourselves.

A delegation of German bishops are preparing to travel to Rome this week to meet with the Vatican about concerns over the German Synodal Way. For a refresher on the situation in Germany, our own explanation can be found here.

In Scotland, a hate crime law passed nearly two years ago will come into effect on April 1, worrying Christians who say that vague wording could cause problems for many seeking to express deeply-held (and traditional) beliefs about the human person and human sexuality.

"It is especially dangerous to enslave men in the minor details of life..." We moderns often find ourselves trapped in regulations, paperwork, and minor demands. What are the consequences of such constraints?

For Catholics, Sacred Tradition stands side-by-side with Sacred Scripture as a main source by which humanity has received God's revelation. Sacred Tradition is at once humbling and purifying.