First Things published a tribute to W. David Solomon this week, who passed away a couple of weeks ago, and who served as a professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame for almost 50 years.

Solomon was a luminary in the Christian intellectual tradition, and a key proponent of the ideals that make for a true, integral education. As the First Things piece signals, his passing makes for a fitting occasion on which to call to mind just those ideals, which he and so many others spent their lives laboring on behalf of.

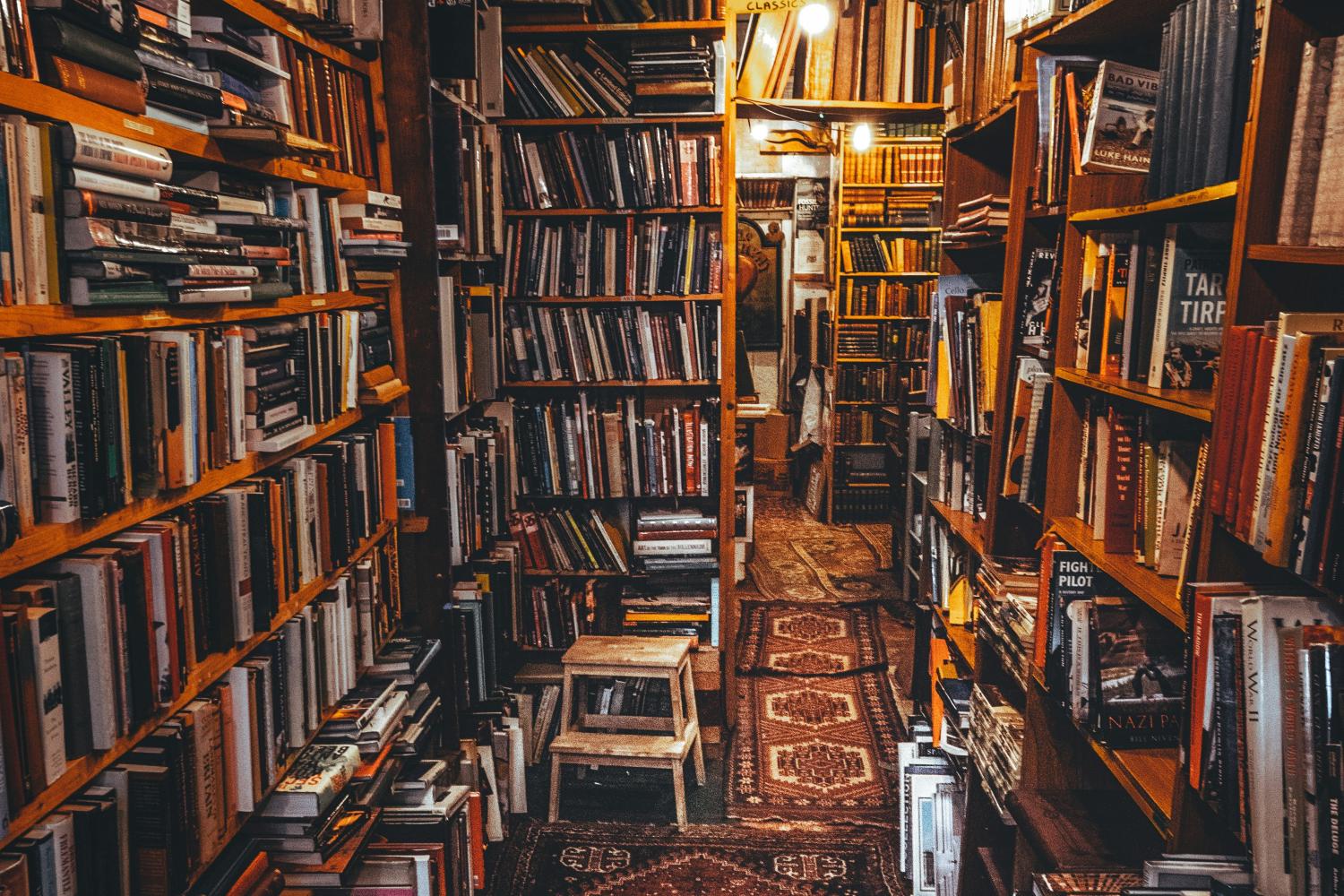

“There is such a difference between life and theory” is the epigraph to the tribute – a quote from Anthony Trollope, which goes a long way to pithily characterize the gap that so often emerges in modern educational schemes. For it’s a gap that, in some ways, lots of universities have wanted to widen. They’ve wanted to believe, for example, that the formation of character doesn’t have a place in collegiate formation, that universities are privileged spaces for considering abstracted, academic “theories” in their own right, without concern for what happens outside the library, the lab, the classroom or lecture hall. Professors and students have no right to pontificate on what bears upon the moral realm, they’ve proclaimed. That realm is one’s private business … and it’s small potatoes, intellectually speaking: to spend time troubling over it would be a distraction, an infringement on or reduction of the real work of university faculties, which is high-level, sophisticated, conceptualized and free thought.

This kind of approach is what thinkers like Solomon and projects like Catholic Studies or the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture that Solomon founded have striven to resist. Commenting on an annual conference Solomon helped to found and convene, the piece notes that “it was a way of fully engaging philosophy, and the academy more broadly, with human life and culture in all of its richness and depth.” This is the way we’re meant to teach and learn – testing our theories against reality, against the way they may be lived from or lived for; testing the ways they make our lives make sense or not, and how they affect the way we relate, the way we work, the way we have friendships, the way we pray.

For there is a difference between life and theory, but it’s not one Trollope is suggesting we should be trying to leverage. The chasm that modern conceptions of education want to assert between these two spheres is illusory: what we believe is true about the world governs the way we live in it, whether we acknowledge that or not. So to decline to bring our theories into relationship with life is to decline to think about our theories well. They become the stale, whimsical ideas that can only persist in the ivory tower of academia, because they’re frivolously incommensurate with the stuff of life. And that’s the other point of Trollope’s quotation – its more chiding, tongue-in-cheek side. To put it another way, when we refuse to bring the intellectual life of the academy into contact with our full spiritual, moral, and cultural life, we’re refusing to do even the intellectual work well. We’ve become disconnected from its full meaning, lost in a realm of untethered, unreal ideas.

So: it’s a good moment today to let ourselves be reminded of a better line of approach. Let’s take this occasion to be reenergized and reconvicted in the educational task we’re invested in, whether as young learners, scholars, teachers, parents, or friends: the task of indeed engaging our thought with “human life and culture in all of its richness and depth.” For all of us are made to think on what’s true, and to integrate our lives around it, in a way that makes of our minds and lives one radiant, inspiring whole – where our mode of life and thought gives witness to the best of “theories,” those deepest, most life-giving truths, which we’re meant to live from and live for.

We moderns have become consumers and viewers rather than growers and makers - as one author puts it, mere “minds with thumbs.” For what have we paid this price? Is it worth it?

T. S. Elliot took a poetic approach to the same problem in “The Hollow Men,” addressing the spiritual emptiness of his age which seems to have continued into our own. Perhaps Lent is a vital antidote for such hollowness.

In a pastoral letter describing the current time as difficult both in the world and in the Church, the prelate of Opus Dei offers a clear response: joy.

John Paul II’s biographer argues that the saint is an ideal model for fighting antisemitism. What insights can we gather for our current socio-political moment?

For many Catholics, indulgences are at best a confusing devotion of an age long past and at worst a case of medieval excess. However, the Church treats them quite differently, as an important aspect of a vibrant Catholic life. How are we to understand indulgences?