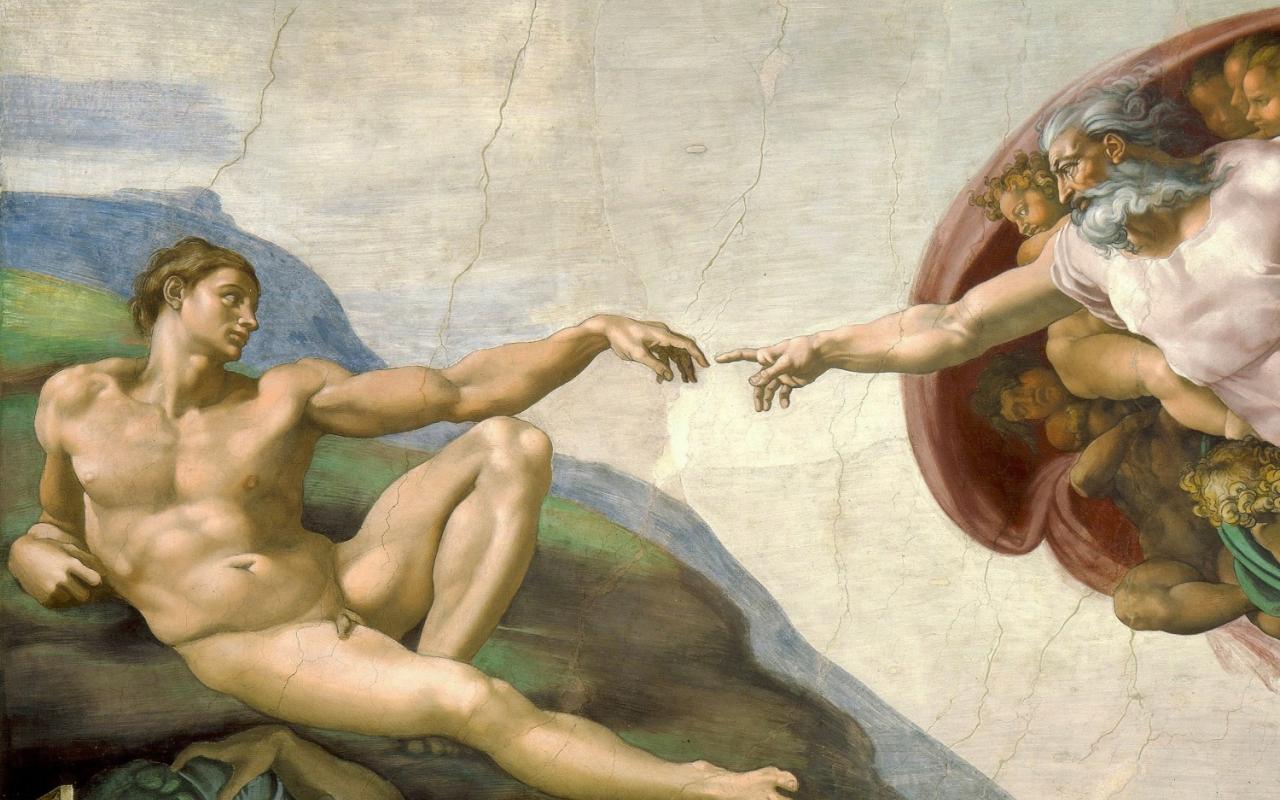

The human person has been created in the image and likeness of God, possessing a normative nature and acutely aware that we have not yet reached our final form.

The question: “What is man? What is a human being?” is the necessary starting point for all kinds of other questions. We can’t begin to think intelligently about politics, education, or personal identity, let alone faith, until we have a settled idea as to what we think about this question. Beginning with the Greeks and developed further by Christian revelation, the Christian centuries developed an understanding of the fundamental structure of the human, one that is expressed in the Christian Scriptures and that was assumed as true for close to two millennia by the civilization founded on that classical and Christian ideal. The anthropological revolution that has been emerging during the last few centuries has thrown much of the Christian view of the human into the air, and we have been wrestling with the question ever since.

Human Nature?

Most of the hot-button issues that so agitate the world around us, though they arise over questions of justice or the morality of specific behaviors, are rooted in disagreements about what a human is. At the back of those disputes is a disagreement over a yet more fundamental question: do humans even have a nature? The question is not just whether humans happen to be arranged in certain ways, physically and psychically. It is obvious that we have physical, mental, and emotional characteristics. The question is rather: Do humans have a normative nature? Is there something we are supposed to be or meant to be? Are there potentialities and limits written into our being? Or are we accidental by-products of a random adaptive process that has landed us where we are for no particular reason?

Christians have held that God is the source and center of all existence, that God created humans with a nature and a purpose in mind, and that we are most ourselves when we become what he has created us to be. Practical materialists of various stripes hold that there is no God who created an ordered reality, and therefore there can be no normative human nature. We are therefore free to be whatever we choose to be, limited only by our practical ability to effect change. Many also hold that our human dignity will be attained only when we take hold of the creative process of molding our own identity. Which of these views is correct and what the necessary consequences are of each view is a crucial matter worth serious investigation. This article does not seek to go deeply into that discussion. Instead it attempts to give a brief sketch of the traditional Christian understanding of the human, what theologians and philosophers have often called a Christian anthropology. Apart from its intrinsic importance, grasping the shape of the human as it has been framed by the Christian tradition is the necessary starting point for understanding the cultural and historical development of our civilization, as expressed in its art and literature, its social and political institutions, and the religious, moral, and cultural ideals that have given direction to its dynamic life.

The Image of God

The most significant truth concerning the Christian understanding of human nature is found in the Genesis account of creation, where we are told that the man and the woman were created “in the image and likeness of God.” This means, among other things, (1) that God is the source of human identity, from which it follows that we can only find our identity if we are rightly related to God; and (2) that in crucial ways, humans are “deiform,” made with a God-like shape, which means that if we want to know who we are, we need to be looking at God to find out.

The Wayfarer

But why should we need to find out? Why is it that we need to go in search of an identity? Why is our identity not a simple given? Chickens, one may assume, do not suffer from a loss of a sense of self. Cows do not become anguished by an identity crisis and abandon their home pastures in search of themselves. The universal experience of a fragile human identity points to another aspect of the Christian view of the human: namely, that we are not yet fully created; we have not reached our final form. Not only that, but God has determined that he will complete the job of our creation only if we willingly cooperate with him. It is as if an artist had brought his work within sight of completion and then had asked the still-unfinished piece of sculpture for help in putting on the finishing touches. This quality of the human as a work in progress has lent both excitement and anxiety to life. We constantly hear, sometimes tritely, a human life referred to as a journey, a road, a path, a quest, even a flight. All these metaphors point to the experience that we are not yet at home. We have not reached the place of fulfillment, not geographically and not ontologically, and while it is exciting to consider arriving at our destination, it is worrisome to think that we might get lost.

God, Not Zeus

If God is the Creator, it stands to reason that he created humans with a purpose and plan in mind, and that humanity needs to be aligned with that purpose in order to thrive. This reality is often expressed by Christians as the need for humans to obey God’s will. The point is clear enough, but there often lurks a misconception concerning God’s nature and his relation to his creation that can cause us difficulties. God can be conceived of as the biggest, most powerful, and most knowledgeable of all the beings in the universe: a sort of super-Zeus. His act of creation is thought of as a kind of craftsmanship: he brought about creatures distinct from himself that now have a life and a center of their own. The error in this view is that it makes God a co-resident with us in the cosmos. We think of him and deal with him as a very large and very strong being who has a mind and a will like ours, but a much more knowledgeable mind and a far more powerful will, and because of that power we need to submit to him. This erroneous way of perceiving God can subtly turn him into a rival of human aspirations, an oppressive totalitarian being whose rule hinders the freedom and fulfillment of the human soul.

The universal experience of a fragile human identity points to another aspect of the Christian view of the human: namely, that we are not yet fully created; we have not reached our final form.

Christians understand the matter very differently. They know that God is not one among other existing beings in the universe. He is outside of time and space, both of which he has created. He is entirely outside of everything that exists, because he is the ground of the existence of everything. His existence is not of the same order as the existence of anything else. He not only got everything going in the beginning; he holds everything in existence moment by moment. Nothing apart from God can exist except by participating in his existence. As St. Paul quotes, "In him we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28). He is at the same time both entirely distinct from his creation and deeply engaged in its being. As theologians like to say, he is both transcendent and imminent in regard to all that he has created.

Clearing up this misunderstanding can help in seeing what Christians mean when they say that humans are created to be ruled by God. They mean that God is the source of our minds, our wills, our thoughts, and our physical existence, and to be firmly planted in God is to come fully to ourselves. To be obedient to God and the order he has established is to be rooted and grounded in that which gives us our identity in the first place. Perfect obedience to God is perfect freedom and the fulness of individual identity. It is not submission to an aggressive outside force; it is the flowering of our inner essence in the soil that sustains our life and brings us to our fulfillment. Jesus was pointing to this truth when he said, “Whoever would save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will save it” (Luke 9:24). Humans will find themselves in God, or nowhere.

The Microcosm

Humans have an odd quality that sets them apart from the rest of the created order. We share a spiritual life with the angels, and a material life with the animals. We are both body and soul, essentially material and essentially spiritual, created from the “dust of the earth” into which God has infused a rational living spirit. This puts the human in a central position with regard to creation; every human is a small world that encompasses the whole of the cosmos. The visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual, the organic and the inorganic, all are present and brought into a unity in each person. Christian thinkers have pointed to this when they have spoken of the “fittingness” of God becoming human in Christ. That God would take upon himself anything of his creation is an unfathomable mystery. But if he were to unite himself to the created order, there was a certain appropriateness in taking the form of the human, through whom he would touch every aspect of his creation, thereby expressing his “preeminence in all things” (1 Colossians 1:18).

The union of materiality with a spiritual soul has also opened human life to another layer of drama. Gertrude Stein once famously wrote, “A rose is a rose is a rose.” That may be the case for roses, but it certainly isn’t true for humans. Unlike roses that presumably enjoy perfect security concerning their inner life, for humans the relationship between the material and spiritual aspects of their being is a fragile one that can easily lose its proper shape, and it has demanded an ordering and integrating principle that can come only from God himself.

The Four Faculties

There is a poetry to the traditional Christian picture of the human, a sacramental sense that the shape of our physical being expresses something of our inner nature. The four main human faculties – the mind, the will, the emotions, and the senses – find their symbolic bodily locations in descending order, corresponding to the healthy ordering of their powers. The mind is seated in the head, the highest place of all; the will comes next, located in the heart; the place of the emotions is the stomach, the gut, or the bowels; and the senses are represented in the lowest place, in the loins. There is an obvious logic to these placements, but they aren’t meant as anatomical descriptors of the soul’s relation to the body. They point rather to the proper harmony meant to exist in the human personality.

The two higher faculties, the mind and the will, are sometimes jointly referred to as the soul; it is here that humans bear the image and likeness of God and share qualities with the angelic order. The two lower faculties, the emotions and the senses, are shared with other animals. Humans are thus “enfleshed souls,” or conversely “ensouled bodies.” All the faculties have their necessary place in a harmonious order.

The mind and the will, the God-like parts of us, are meant to govern the lower faculties, the emotions and the senses. The mind is the faculty of appropriating knowledge of every kind, and is drawn to all that is real and true. The will, called by some the “rational appetite,” is the faculty that is naturally attracted to goodness, and moves toward gaining the good things that the mind perceives as true. The perfect fulfillment of the powers of mind and will is found in knowing and loving God, the One who is truth and goodness personified. The emotions, sometimes called the sentiments or the passions, are given to us as natural qualities that anticipate and respond to good and evil around us, and that deepen our enjoyment of what is good and our rejection of what is evil. The senses provide our connection to the material world and through the material world our ability to find communion with other enfleshed souls. They provide the raw material for the mind’s knowing.

To speak of these faculties individually is a little like speaking about different aspects of our anatomy in the abstract. There is a point to talking about the circulatory system, the nervous system, and the skeletal system in order to understand each of their proper workings. But physicians and nurses always keep in mind the one really existing reality, the unified human. No one ever met a circulatory system wandering on its own. So here, the four faculties do not act independently of each other; their operations are tied together and react upon each other in ways that are integrated into a single being.

When our faculties are working in harmony, with our minds rightly perceiving what is true and good, our wills moving us toward action that will gain that truth and goodness, our emotions supporting and deepening our experience of goodness and truth and helping us to avoid their loss, and our senses actively and accurately engaged, we are at our most truly human. Consider the kinds of activities that we consistently find most interesting, enjoyable, worthwhile, or gratifying: things like participating in a celebratory feast; playing or watching a sport; attending or singing in a concert; enjoying a long-term relationship of friendship and love; attending a worship service. These, and hundreds of other human activities like them, demand for their proper working a harmonious order among our faculties. If that order is upset, things go awry.

Sacramentality describes the proper relationship of soul and body, spiritual and physical, visible and invisible. Christians, knowing that we are enfleshed souls, honor all the aspects of our nature, only insisting that they be rightly ordered such that they can produce harmonious melody rather than discordant noise.

As an example consider the feast; in this case we will say a gathering of family and friends to celebrate a 25th wedding anniversary. The mind governs the celebration from start to finish, determining that it is a good idea in the first place, planning and organizing the details, thoughtfully preparing the food, and arranging matters such that the guests are invited and the various aspects of the celebration come together in good order. The will of the participants is evident in their desire to honor the beloved couple, their readiness to help in any way necessary, and their determination to be attentive and fully present for the celebration. Sentiment is found in the joy of meeting together, in affection and admiration for the honorees, and in the laughter and poignancy of toasting and story-telling. The senses mediate all that is going on, and all five senses are engaged, in the round of food and drink, in the good music and pleasing décor, and in the warm congratulatory embraces.

When the proper harmony of the four faculties is disturbed, things go badly and the happiness of the participants is affected. Maybe the problem is with the mind: the event was ill-planned and sloppily executed and nothing seemed to go right. Maybe it is the will: the attendees were lackluster in their participation, not really having wanted to come and just waiting for a chance to leave. It might be disorder in sentiment, when Uncle Henry and Uncle Fred let their emotions get the better of them and got into a shouting match that ended in a brawl. Maybe the problem is with the senses, when one of the guests got rip-roaring drunk, and after making himself a serious nuisance passed out into the cake.

What Went Wrong

In Eden, we can presume, Adam and Eve enjoyed a peaceful inner life, all their faculties in harmonious order operating with the beauty of a well-trained choir. Because their minds and wills were in tune with the mind and will of God, their emotions and senses played their proper supporting role. Duty and delight were synonymous, and self-control was as natural and as easy as breathing. They were entirely themselves.

When our race insisted on its independence from God and turned our backs on the source of our life and identity, the harmony of our inner nature was lost and cacophony began to prevail. Our mind, now cut off from God’s light, became darkened, wounded in its ability to know the truth. Our wills became hardened and often propelled us down paths of illusory goods. Our emotions and our senses were inflamed and attempted to overrule and enslave our higher faculties of mind and will. Every human soul became a battleground, aptly described by St. Paul in his letter to the Romans: “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. So I find it to be a law that when I want to do right, evil lies close at hand. For I delight in the law of God, in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin which dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” (Romans 7:15, 21-4).

Fortunately, St. Paul also gives us the answer: “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord! (Romans 7:25). Christ, the divine physician, works in the believer to restore heaven’s harmonies to the soul. Once our minds and wills have been brought back to communion with the mind and will of God, the operation can begin for the reshaping our inner being. Paul speaks of this process in his letter to the Ephesians. First he describes the wound: "You must no longer live as the Gentiles do, in the futility of their minds; they are darkened in their understanding, alienated from the life of God because of the ignorance that is in them, due to their hardness of heart." Then he points to the cure: "Put off your old nature which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful lusts, and be renewed in the spirit of your minds, and put on the new nature, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness" (Ephesians 4: 17-18; 22-4).

Disharmonies

Every human has experienced the internal battle described by St. Paul, and every human culture has attempted to map out roads to harmony and peace, within the individual soul and in human social relations. It could be said that the quality of a human culture can be assessed by its tendency to encourage the proper ordering of the inner life of its members, individually and socially. A Christian culture, whether it is the overall pattern of a society or the local culture of a family, a business, or a group of friends, is one that has enshrined a Christian anthropology in its ideals, its institutions, and its educative activity to a significant degree (no human culture is ever fully Christianized). It may be of use to briefly recount some of the commonly recurring but mistaken ways of ordering our faculties that in one way or another warp our humanity.

1. Hedonism (The senses rule.)

This attitude says: whatever is most comfortable, whatever gives us the most intense physical pleasure, should be allowed to dominate us. “If it feels good, do it.” Even a little intelligence and experience will show that this is not a road to happiness or peace, and as a philosophy it is hardly worth arguing against. But many people are occasional hedonists. Consider the typical club atmosphere: pounding music, flashing lights and dark corners, drugs and drink, everything in the environment saying: “Don’t be a human, be a hippopotamus. Shut off your mind, close down your will, and abandon yourself to your sensual instincts.”

2. Sentimentality (The emotions rule.)

With its most recent roots in the Romantic movement, this attitude insists: “I am most myself in what I feel. I need to be true to my feelings even if following them seems to be irrational or wrong.” One often encounters this way of thinking in the approach to erotic love. One is told to “follow one’s heart,” which usually means that a strong emotion should overrule what our minds and our wills may be saying about the truth or goodness of what we are doing. Much modern religion also tends to the sentimental. Success is measured by gaining a particular emotive experience rather than by an insertion into what is true and good.

3. Gnosticism/Stoicism (The lower faculties of sentiment and sense are alien to humanity and should be eradicated.)

Many sophisticated human philosophies have gone down this road. Buddhism and some currents of Hinduism in the East, Stoicism, Gnosticism and Neo-Platonism in the West, have tended to one degree or another to denigrate the lower faculties. Rightly recognizing that the invisible soul is more noble than the visible body, and seeking the unchanging eternal in the midst of a passing world, this attitude views humans as immaterial souls that have been snared by materiality and change, and that need to free themselves from the alien storms of emotion and sensual desire in order to find human fulfillment.

4. Intellectualism (The mind is all that matters.)

This ancient view has resurfaced in ultra-modern philosophies among transhumanists and proponents of artificial intelligence who see the human as a kind of computer. We are, essentialy, our brains. The software brain (the reality) is currently occupying a “wetware” body that can be tossed aside without loss when something better can be devised.

5. Nietzschean Critical Theory (The will is everything.)

The roots of this modern attitude are in the late Medieval period among thinkers like William of Ockham and the nominalists. For some time it has been a popular, even faddish, phenomenon in university humanities departments, and has recently seen a surge of expression in the wider society. According to this view, the fundamental and overriding human faculty is the will. There is no such thing as objective truth that the mind can grasp. All attempts to insist on truth or rationality are only hidden power moves, the attempts of one will or group of wills to gain hegemony over others.

The Christian Sacramental View

Each of the preceding five ways of seeing the human is appealing to something authentic in human nature. The problem with each is a wrong ordering of the powers of mind and body such that things are thrown out of balance. If one were to ask what the proper harmonious order looks like, the brief response would be the Christian sacramental vision. Sacramentality describes the proper relationship of soul and body, spiritual and physical, visible and invisible. Christians, knowing that we are enfleshed souls, honor all the aspects of our nature, only insisting that they be rightly ordered such that they can produce harmonious melody rather than discordant noise. The necessary beginning for that healing process is the restoration of communion with the Source of all.