George Weigel's Letters to a Young Catholic explores and comments on Catholic culture, examining history and theology, art and architecture, literature and music. This article is the fifth in a series that walks through Weigel's work letter by letter, providing imagery to enhance the reader's experience. Here we explore "Letter Five, The Oratory, Birmingham, England: Newman and 'Liberal' Religion." Click here to view the entire series.

Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem. As an old man, John Henry Cardinal Newman wished to have this phrase carved as an epitaph on his tomb because he thought it summed up the whole of his life’s path and trajectory: from shadows and fantasies into truth. Newman converted to Catholicism in 1845 and suffered from accusations of vanity and inconstancy in religion as he moved from boyhood atheism to evangelical and liberal Anglicanism and thence from a high church Anglicanism focused on ritual and tradition before becoming Catholic. These accusations deeply hurt him, because he saw this movement not as a vain or emotional pleasure-seeking but as a search for truth, as a movement from shadows to light. He felt compelled to defend and describe this journey in a spiritual autobiography, the Apologia pro vita sua. In it, Newman sought to do a very modern thing: explain to the world his intellectual and interior journey from the proper and acceptable liberal Victorian Anglicanism toward the scandalous and scruffy Catholicism.

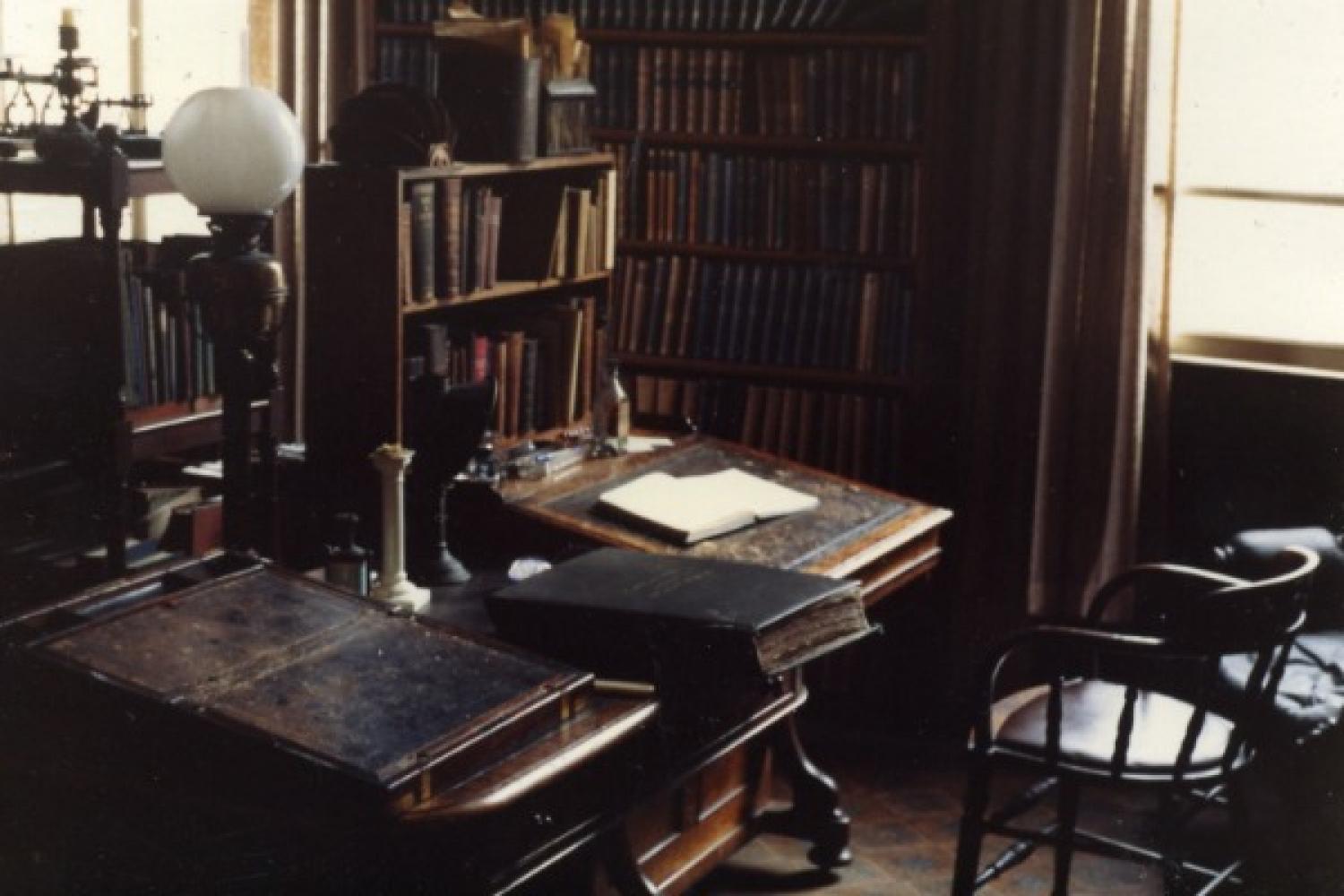

In the fifth chapter of Letters to a Young Catholic, Weigel takes us to the Oratory in Birmingham, England, where Newman spent his last years after his conversion. Newman’s conversion was anything but triumphal, as he went from being a respected Anglican clergyman and don among the dreaming spires of Oxford to founding and running a boys’ prep school in unglamorous and industrial Birmingham. Especially painful was the loss of friendships as his Oxford and Anglican friends abandoned him one by one after his conversion, only to be greeted by Catholic misunderstanding and mistrust. He was deeply committed to university education but had difficulty convincing fellow Catholics of its importance. Yet amid all these difficulties, Newman penned some of the most important texts for Catholicism in the modern age. Weigel takes his readers to Newman’s private rooms and to his library in the Oratory, crammed with books and notes, where his private altar, his standing desk, and library are all as they were on the day he died. Postcards, rosaries, prayer requests, and newspaper clippings reveal a man still deeply engaged and concerned with the modern world around him. Here, he prayed and wrote his Apologia and sketched out the Idea of the University and A Grammar of Assent in which he grappled with how we can know Truth.

Newman’s library and study are glimpses of a man grappling with the claims of the reigning religious liberalism of his day, finding it wanting, and then straining to obtain the truth. After long study and earnest prayer, he saw it: the liberal religion of his youth denied the possibility of objective truth, robbing Christianity of its vitality and dynamism, reducing belief to a matter of private opinion and feeling. Truth is something revealed by God, not curated according to personal taste, and because it is something outside of us, not created by us, then we must conform our lives to it. By contrast, liberal religion’s rejection of Truth ultimately led to a genteel skepticism about whether we can know anything as true at all. This understanding led Newman to risk everything, his career, his friendships, his livelihood. He wrote: “You must make a venture; faith is a venture before a man is a Catholic; it is a gift after it. You approach the Church in the way of reason, you enter it in the light of the Spirit.”

Newman founded the Birmingham Oratory in 1849, and it remained his home throughout his life as a Catholic. The current Oratory church was completed in 1910, constructed as a memorial to Newman. (Video by Corpus Christi Watershed. See video credit A.)

Newman's personal chapel - constructed in his room at Birmingham - offers us insights into his intense interior life. (Video by Corpus Christi Watershed. See video credit B.)

Video Attribution A: "Birmingham Oratory Church" by Corpus Christi Watershed, shared with their generous permission.

Video Attribution B: "The Cardinal's Private Chapel" by Corpus Christi Watershed, shared with their generous permission.

For more videos on the life of St. John Henry Newman at the Birmingham Oratory produced by Corpus Christi Watershed, click here.

Next: Chesterton's Pub and a Sacramental World

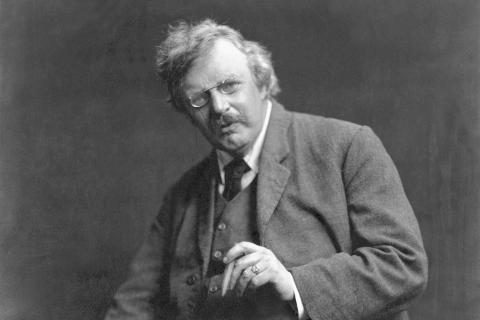

In the sixth chapter of Letters to a Young Catholic, Weigel explores Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese to reflect on the life and vision of G.K. Chesterton.

Previous: Mary and Discipleship

In the fourth chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores the Benedictine Abbey of the Dormition in Jerusalem to reflect upon Mary's unhesitating "fiat" to the will of God.

The First Draught

To receive the Weekly Update in your inbox every week, along with our weekly Lectio Brevis providing insights into upcoming Mass readings, subscribe to The First Draught.