George Weigel's Letters to a Young Catholic explores and comments on Catholic culture, examining history and theology, art and architecture, literature and music. This article is the sixth in a series that walks through Weigel's work letter by letter, providing imagery to enhance the reader's experience. Here we explore "Letter Six, The Olde Cheshire Cheese, London: Chesterton's Pub and a Sacramental World." Click here to view the entire series.

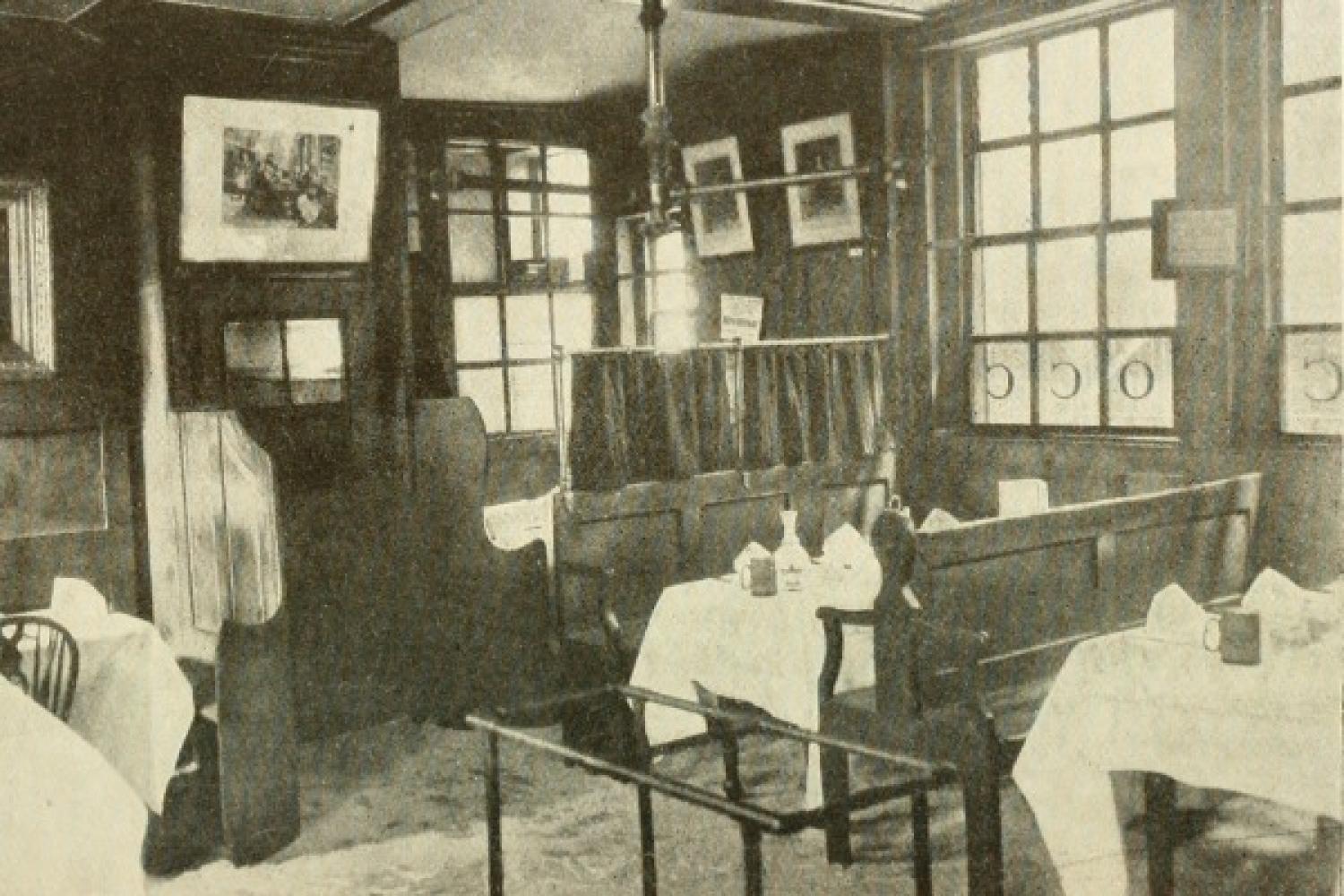

If you turn down a narrow alleyway off Fleet Street in London, you will cross the front step of one of the oldest pubs in London, the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese. Walk through its unassuming entrance and you are ushered into a dark, cozy rabbit warren of rooms. There’s sawdust on the creaky wooden floor to soak up spilled beer, wood paneling infused with centuries of pipe smoke climbs the walls, and old gilt paintings of indeterminate age hang in the various nooks where patrons are warmed by open fireplaces. There’s little natural light and the cell service is awful, but that’s not why you are here. You’ve come for the hum of quiet conversations and raucous debates over pints of ale, for sociability and friendship. Patrons have been coming here since 1667, when the pub was rebuilt after the Great Fire of London, especially the writers and journalists of Fleet Street, among them Gilbert Keith Chesterton.

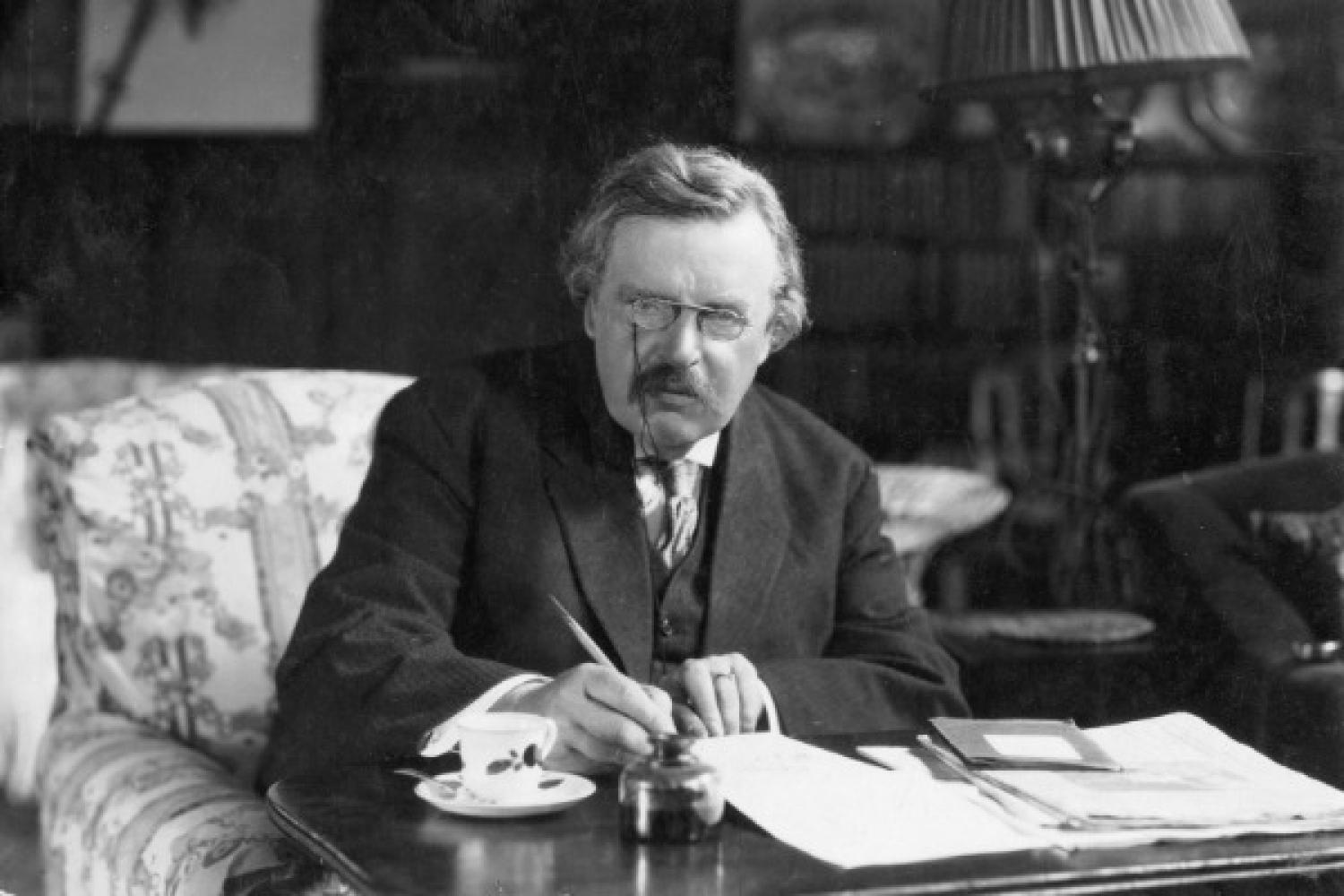

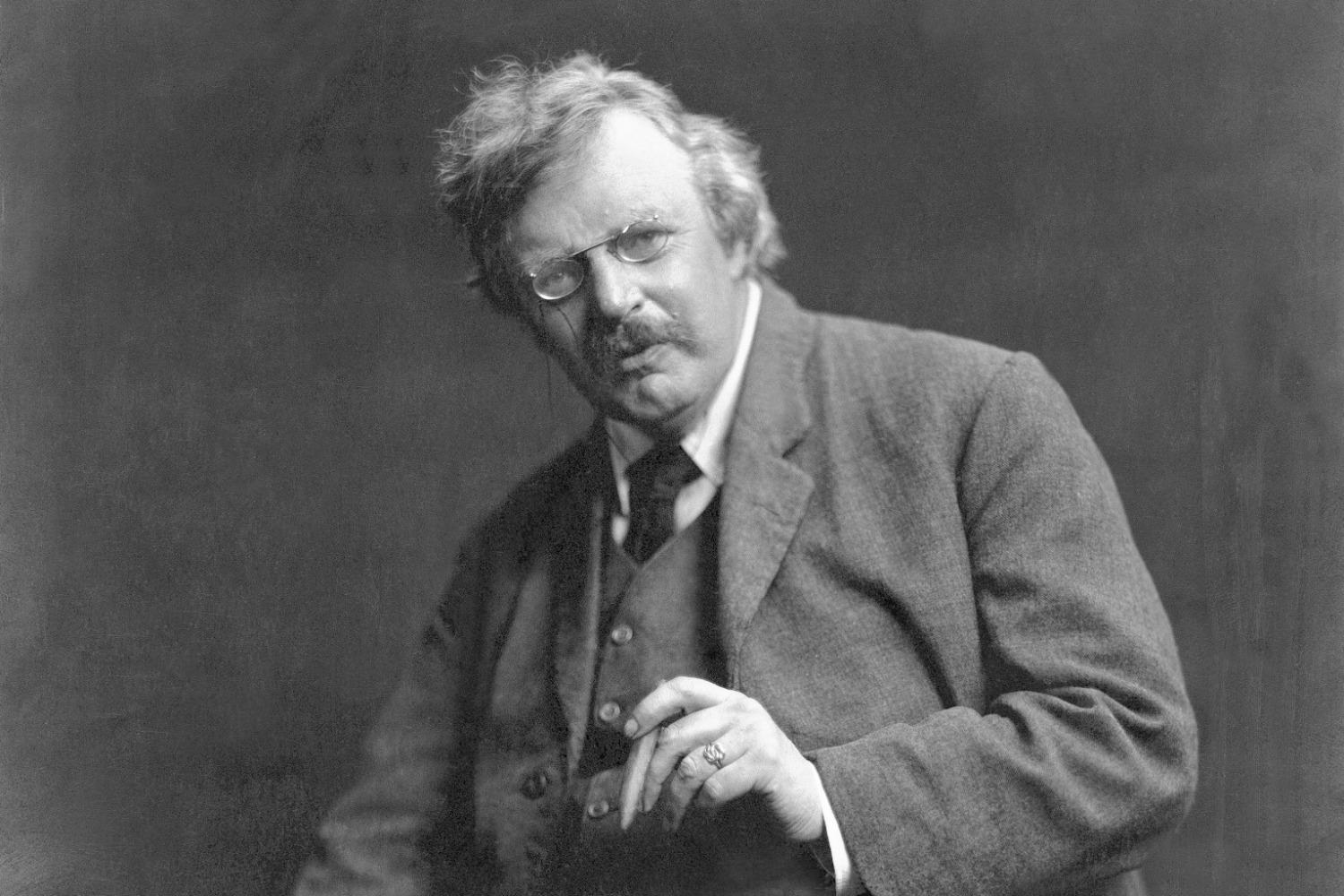

It is to this place that George Weigel calls his young readers in the sixth letter of Letters to a Young Catholic. Weigel is an admirer of the work of the famed early twentieth-century journalist, writer, and convert, G.K. Chesterton. Chesterton was renown for his jovial and spirited public engagement with the secular pieties of his day. He loved a good argument and loved to take on any and all challenges to orthodox Christianity, preferring to use humor and satire to highlight the absurdities of a modern, secularizing society. This pub, the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, was one of his favorite haunts where he often entered enthusiastically into debates with the likes of Hilaire Belloc and others.

Weigel takes Chesterton’s favorite pub as an opportunity to explore a topic on which Chesterton often wrote: the distinctiveness of the sacramental imagination, that way of seeing the material world as disclosing and revealing some deeper spiritual, immaterial reality. The stuff of the world around us is a signpost to the hidden reality of the One who created it, and it’s through those signs that God communicates His divine life to us. That’s what a sacrament is and that’s what a sacrament does: it is both sign and instrument of God and his grace. Although Catholicism has seven sacraments in its liturgical life, it sees all of creation—the material world—as sacred and a sacrament, manifesting, revealing, and communicating the inner life of the Triune God. And so, there’s something about a physical, material thing—a pub, beer, fish and chips, pipe smoke, wood, poetry and debate shared in the context of human friendship—that speaks to us of the real Real, Heaven.

Weigel then contrasts this sacramental vision of the world to the one-dimensional materialism of the present day, naming it a gnostic imagination. This fragmented and impoverished vision of the world will say on the one hand that the material world is all that there is, and on the other hand say that the material world doesn’t really matter. A gnostic vision doesn’t see nature, our bodies, place, or any other material thing as signaling a deeper, more profound spiritual reality. And thus, there’s no meaning in the material world, except what we assign it. It’s not holy, it’s just a thing to be used, abused, or thrown away. Weigel observes that it’s this sort of secularism that Chesterton loved to overturn. Chesterton reminds us that to love the world in all its material and spiritual reality is a right and good thing, and that to see and appreciate the depth and the beauty of a person or a thing as it truly is is to come to see something of the face of God.

Photo Attribution A: "Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese" by Tom Simon James is liscended under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Photo Attribution A: "Eagle and Child (interior)" by Tom Murphy VII is liscended under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Next: Brideshead Revisited and the Ladder of Love

In the seventh chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores Castle Howard in Yorkshire, England, to reflect upon the choice offered to us all: submit to reality or fly into fantasy.

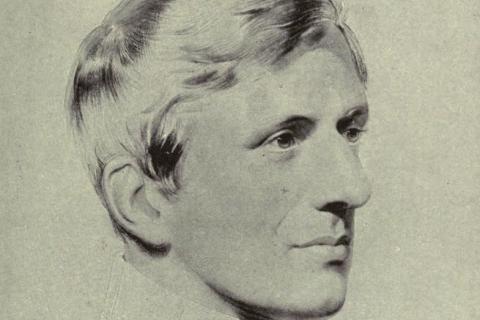

Previous: Newman and 'Liberal' Religion

In the fifth chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores the Birmingham Oratory to reflect on the conversion, life, and theology of St. John Henry Newman.

The First Draught

To receive the Weekly Update in your inbox every week, along with our weekly Lectio Brevis providing insights into upcoming Mass readings, subscribe to The First Draught.