Among the many (too many to count) contributions made by monks to the development of our civilization, there is one that we tend to take for granted, without which the whole development of Western music would have been a much more difficult affair. That gift is the development of musical notation.

All people love to talk, and all people love to sing, and every human culture has developed its own language and its own musical traditions. Through most of humanity’s time on earth, both language and music were transmitted orally from one person and one generation to the next. If you wanted to know what someone said, you either had to hear the person say it or get it from someone who had committed it to memory. If you wanted to learn a tune, you needed to listen to someone who would sing it for you. Highly developed civilizations have been characterized by the remarkable development of literary notation, by which we can read the very words of Moses, Julius Caesar, Confucius, and Stan Lee. Written language has been a great help in maintaining the continuity of culture and in preserving for future generations the wisdom gathered from the past. Musical notation, on the other hand, has been a harder venture. How does one get a musical note into written form? Ancient civilizations seemed to have developed some forms of musical notation, but the few examples that have survived are almost impossible for us to decipher. That’s why we know much more about ancient architecture and ancient literature than about ancient music. We can see the buildings and read the words; but those voices and instruments, however beautiful they may have been, have fallen silent, and we can’t recover their sound.

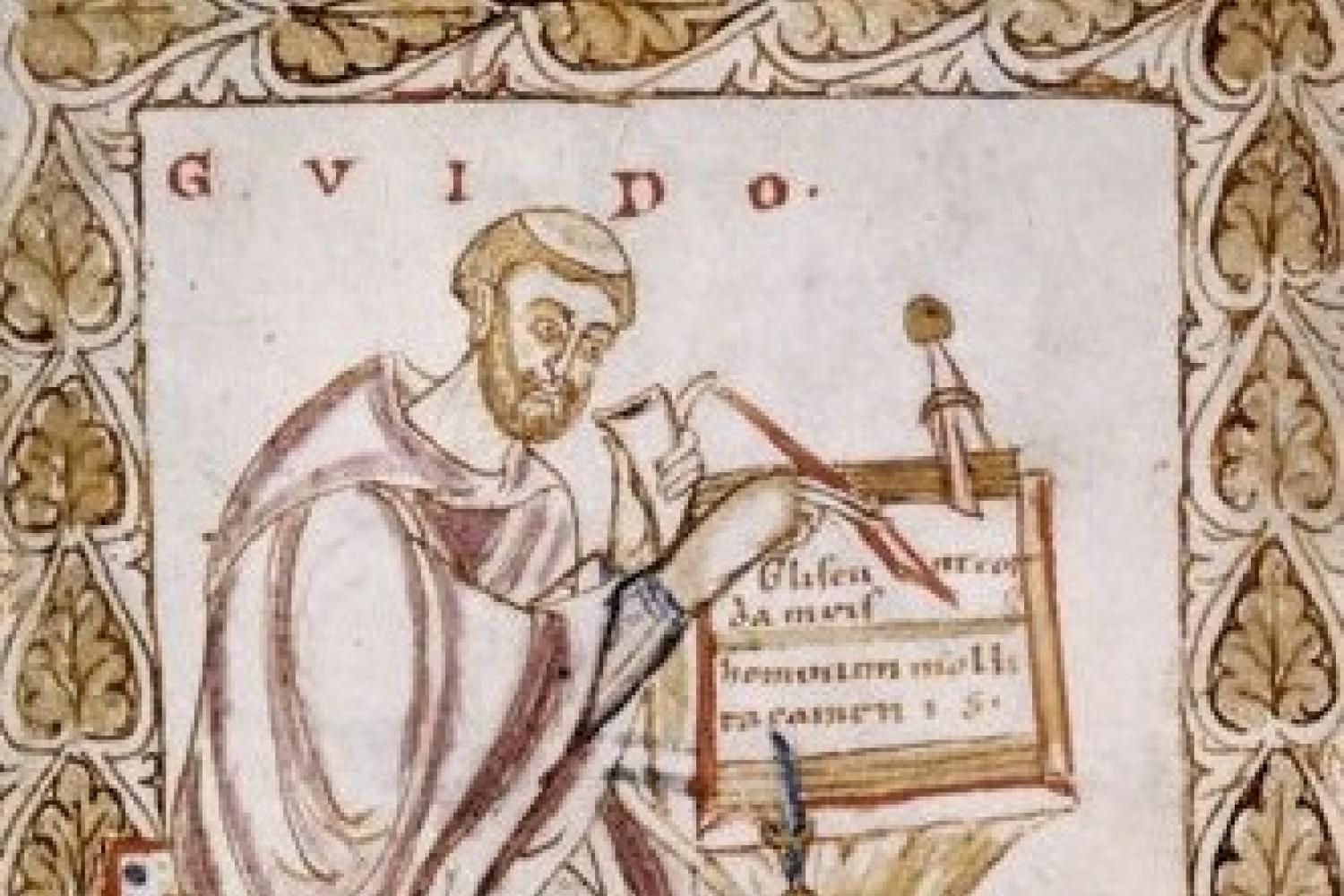

That situation changed around the turn of the first millennium. Monasteries sing the praises of God all day, and as Gregorian chant developed and became widespread in the early Medieval period, monks wanted to find ways to preserve their various chants and teach them to young monks. Enter Guido of Arezzo, a monk from the north of Italy. Building on earlier music theory, Guido solidified the various attempts at musical notation that had preceded him, and decisively improved them with two striking innovations. One was the placing of hexachord notes on a four-line staff, inventing the notation that is still used for singing plainchant, and from which all the modern forms of musical notation have developed. A second was giving the notes on the diatonic scale the familiar “do-re-mi” system, a system still being used in much musical education.

As a result of Guido’s innovations, the possibility of sight-reading first emerged, and music could be shared at great distances and could be sung by people who had never heard it performed. A kind of revolution took place, allowing the emergence of a community of musicians across space and time who could build upon one another’s work and create musical traditions that could be preserved and passed down. Imagine an orchestra and choir trying to learn by ear Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, or a pianist attempting to master a Chopin nocturne by listening carefully to someone else playing it. Without a system of notation it would be simply impossible.

So the next time you enjoy the performance of an orchestra or choir, or search the net for the chords to your favorite pop tune, or take in one more viewing of “The Sound of Music,” tip your hat to Guido of Arezzo and the medieval monks. We stand on the shoulders of giants.

The First Draught

To receive the Weekly Update in your inbox every week, along with our weekly Lectio Brevis providing insights into upcoming Mass readings, subscribe to The First Draught.