If you were in a trivia game and the question came: “What is the largest Church in Christendom?” you’d no doubt know the answer: St. Peter’s in Rome, of course. If the next question was: “What was the largest Church in Christendom before St. Peter’s was rebuilt in the sixteenth century?” many of us might be stumped. And reasonably so, because that church is no longer with us. The answer would be: The Abbey of Cluny. Cluny was not only a physically large place; it was the center of European Christendom for centuries, vying and even surpassing Rome in some aspects of its influence.

Cluny gave its name to a great revival of Benedictine Monasticism, the so-called Cluniac revival, soon after its foundation in 910, in the Burgundy region of France. During the next 200 years, Cluny was almost coterminous with European Catholicism. What gave it such an influence? It has to do with the varying fortunes of Benedictine monasticism.

St. Benedict founded his monastery in the sixth century, and Western monasticism flourished during the next few centuries, becoming centers of faith, learning, and social stability. But during the ninth century monastic life fell into decay. The main reason for this was that monasteries were founded by aristocratic benefactors who controlled their life together, and as abbeys became wealthy and influential their sponsors, wanting to gain influence and wealth, would put their own people in as abbots, many of whom were uninterested in the spiritual disciplines of monastic life.

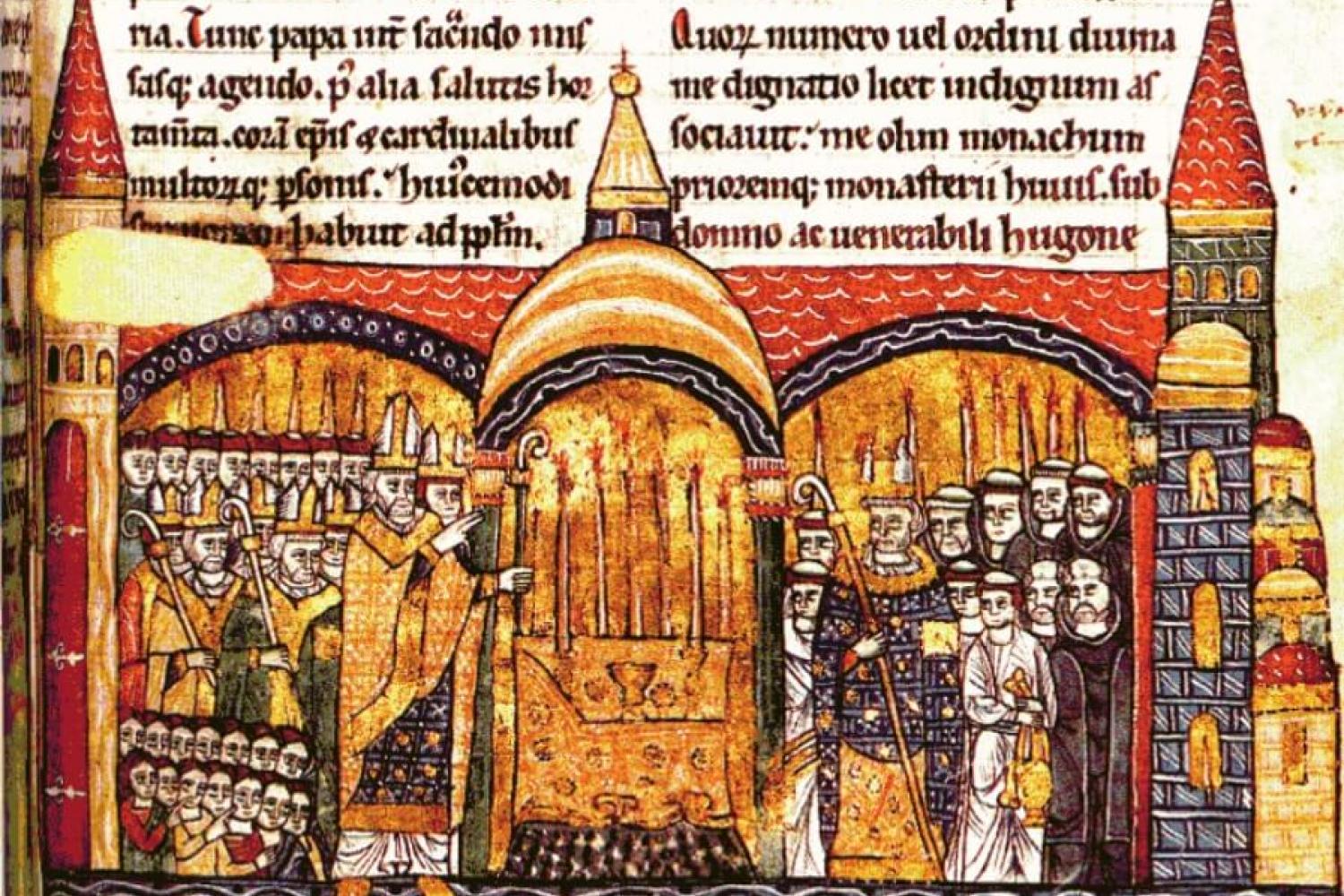

In 910, a house was established at Cluny by Duke William of Aquitaine with the stipulation that the monks were to answer only to the Pope and not to the local benefactor or to the local diocese. This set on foot a revolution of sorts among European monasteries, many of which sought to connect themselves to the Cluniac reform. At the height of its influence something like 1200 monastic houses comprising 10,000 monks were part of the Cluniac family, all of which looked to the Abbot of Cluny as their superior. It was the first religious order to develop in the Western Church.

Cluny was blessed with a run of remarkable abbots, some of whom were later canonized, and all of whom were gifted in both spiritual and administrative leadership. Notable among them were St. Odo of Cluny (abbot from 927 – 942), St. Odilo of Cluny (abbot from 994 – 1049), St. Hugh of Cluny (abbot from 1049 – 1109), and Peter the Venerable (abbot from 1122 – 1156). Hugh of Cluny was a great supporter of the much-needed reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII (1073 – 1085), who had been influenced as a young monk by the Cluniac revival.

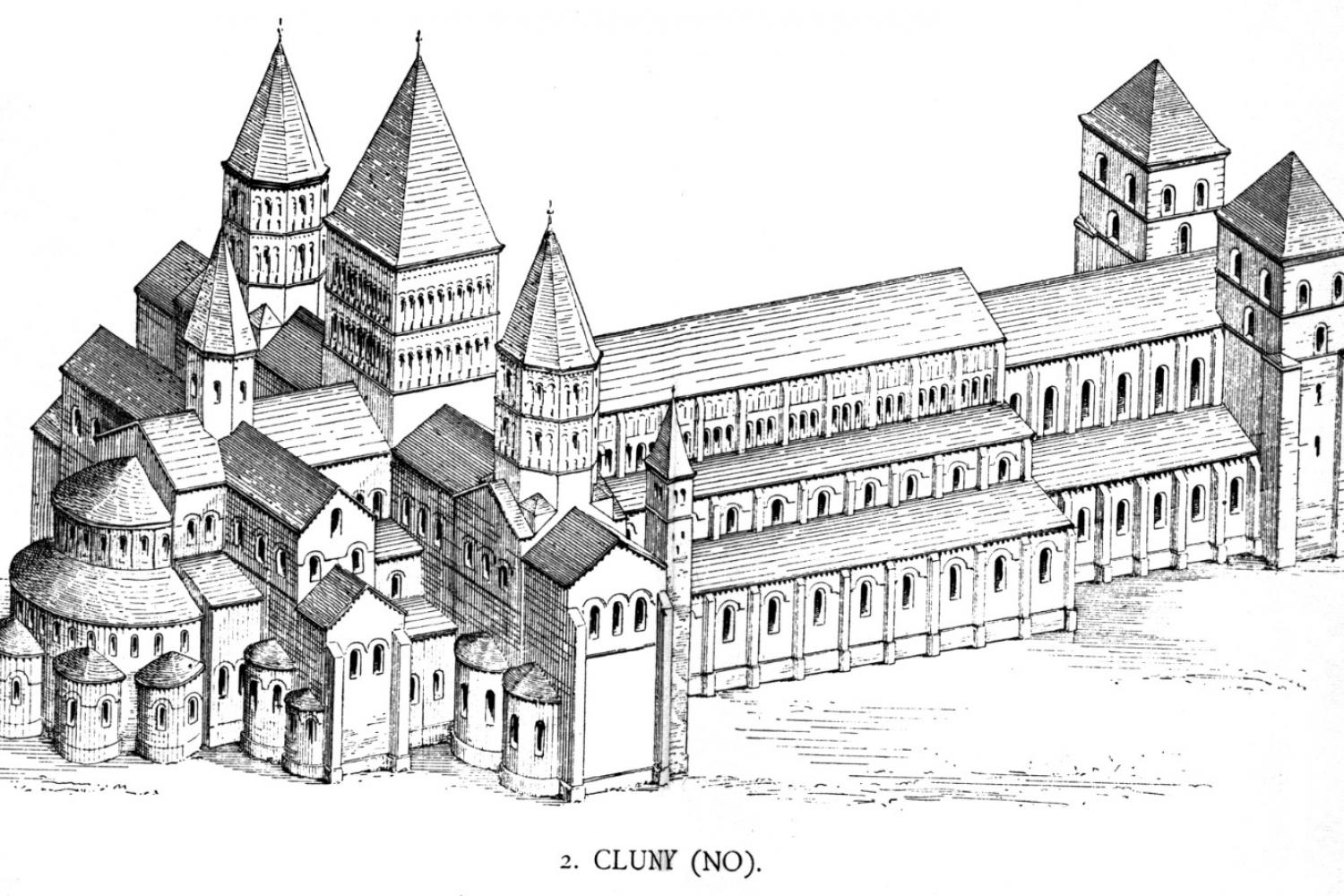

The monks of Cluny re-established the Benedictine rule in greater purity and were especially influential in adorning the liturgy. They also fully developed the architectural style called Romanesque, and erected at Cluny a huge Romanesque Church that spoke of Cluny’s place as the spiritual center of Europe. What happened to that magnificent Church? As with so much of Christian Europe it was sacked and destroyed by French revolutionary armies and its stone used as a quarry. If you pay a visit, you can still see part of the skeleton of the old Abbey.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the main impetus for Benedictine reform moved from the monks of Cluny to St. Bernard and the newly formed order of the Cistercians. Yet Cluniac monasteries continued to be important monastic centers through the centuries and down to the present day. While Cluniac influence has not been historically strong in the United States, a recent monastic foundation at Clear Creek in Oklahoma is squarely in the Cluniac tradition.

The First Draught

To receive the Weekly Update in your inbox every week, along with our weekly Lectio Brevis providing insights into upcoming Mass readings, subscribe to The First Draught.