George Weigel's Letters to a Young Catholic explores and comments on Catholic culture, examining history and theology, art and architecture, literature and music. This article is the third in a series that walks through Weigel's work letter by letter, providing imagery to enhance the reader's experience. Here we explore "Letter Three, St. Catherine's Monastery, Mt. Sinai and the Holy Sepulcher, Jerusalem: The Face of Christ." Click here to view the entire series.

In the third chapter of his book, Letters to a Young Catholic, George Weigel takes us to two places in which we are confronted by the reality of Christ, the Word made Flesh: St. Catherine’s Monastery, home of Christos Pantokrator, and the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

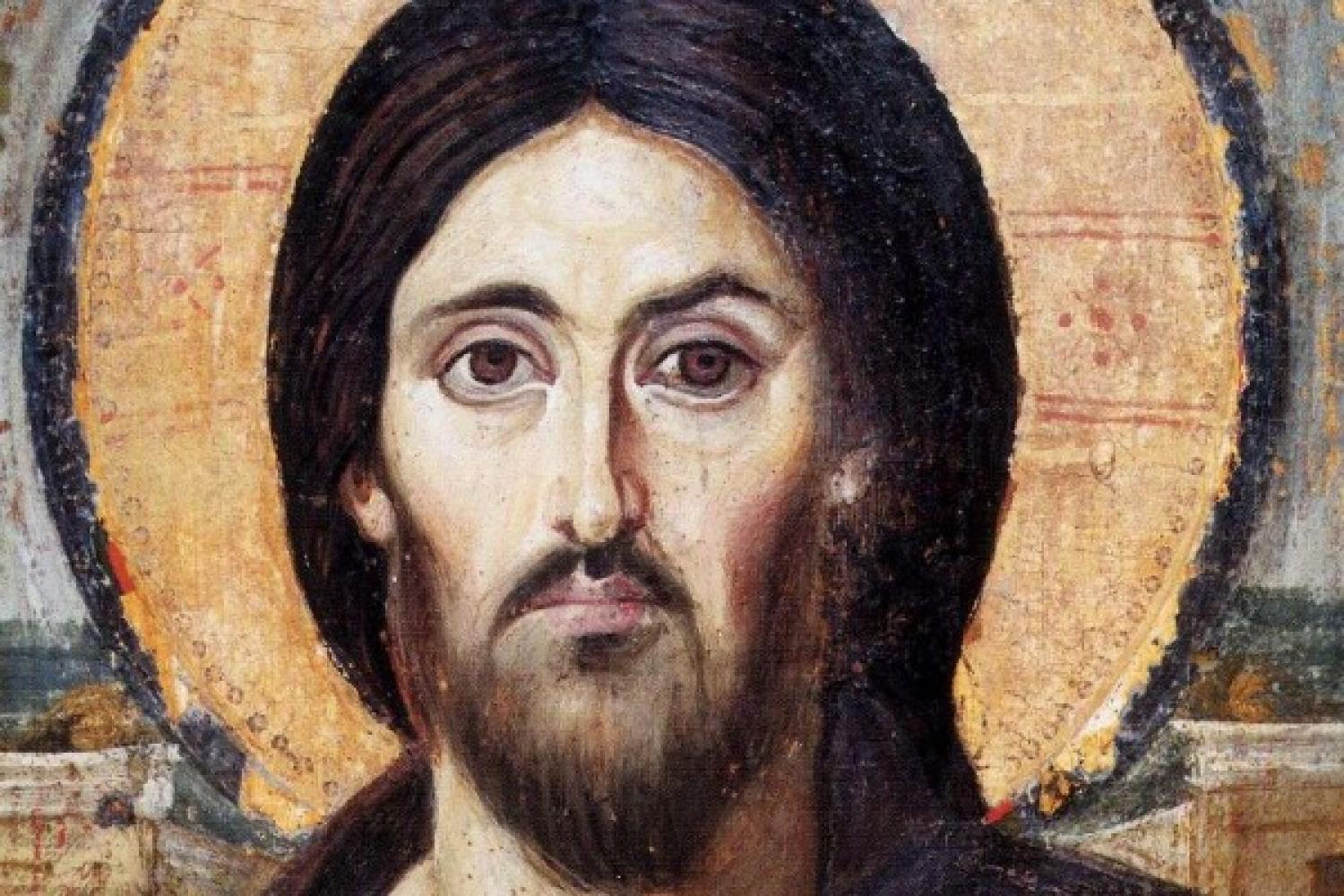

Nestled at the dusty foot of Mount Sinai among the ancient hermitages of the Desert Fathers sits St. Catherine’s Monastery, founded by the emperor Justinian in 527. This remote monastery is the home of Greek Orthodox monks who have in their care one of the oldest and greatest Christian icons, Christos Pantokrator. You’ve seen it: Christ, His right hand raised in blessing, the Word made flesh holding the Word of scripture in His left hand, gazes directly at the viewer and yet past her, into eternity. Weigel uses this particular icon to reflect on the bloody iconoclastic controversy that rocked the church in the eighth and ninth centuries, in which Christians fought over whether it was idolatry to use images of God in worship. The iconoclasts argued that to create an image was to create an idol, something expressly forbidden by the 10 Commandments, and destroyed thousands of icons as a result. The icons of St. Catherine’s were spared destruction, remote as they were in the desert fastness. The Second Council of Nicaea ended the conflict by declaring that because the incarnate Christ is an image Himself—the bodily Image of the very life of God—this means that God Himself is an iconographer, one who makes and uses icons or images. Far from being like men who use images as idols to reach out to control the Divine, God uses images—and a specific Image in His Son—to reach out to us to invite us to share in His life, thus rendering the use of images as permissible and even salutary.

The startling claim that the Word was made flesh is mysteriously encountered in the luminous face of Christos Pantokrator. This brings Weigel to reflect on one of the great teachings to emerge from the Second Vatican Council, that not only does Jesus Christ reveal the heart of God to us, He reveals man to himself. In a modern world in which we so easily forget who we are and what we are meant for in ways that lead us to act and become un-human and inhumane, Christ reminds us of the possibility of our own divinization—that in becoming like God, we paradoxically become more human.

Weigel ends his letter with a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, built over the site of Christ’s crucifixion and the tomb from which He rose. Crowded with pilgrims, disorienting and filled with the distracting noise of competing Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Coptic monks, it seems an unlikely place to encounter Christ. And yet, Weigel tells us, it is precisely in these messy circumstances that we understand that God “came searching for us” in the grittiness of human existence. Unlike the gods of the gnostic mystery religions of old that kept their distance from the dirty complexities of human life, Christ entered them, took them on, and gave them new meaning. The icon of Christos Pantokrator and the Holy Sepulchre confront us with the central, radical claim of Christianity: God became flesh and dwelt among us. In Christ, God searches for and reaches out to us, revealing to us who He is and who we truly are, for “Christ reveals man to man.”

Photo Attribution A: "Saint Catherine's Monastery on the Sinai Peninsula" by Joonas Plaan is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Next: Mary and Discipleship

In the fourth chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores the Benedictine Abbey of the Dormition in Jerusalem to reflect upon Mary's unhesitating "fiat" to the will of God.

Previous: The Grittiness of Catholicism

In the second chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores the grittiness and historicity of Christianity, focusing on the bones of St. Peter in the Vatican excavations ('Scavi').

The First Draught

To receive the Weekly Update in your inbox every week, along with our weekly Lectio Brevis providing insights into upcoming Mass readings, subscribe to The First Draught.