George Weigel's Letters to a Young Catholic explores and comments on Catholic culture, examining history and theology, art and architecture, literature and music. This article is the eighth in a series that walks through Weigel's work letter by letter, providing imagery to enhance the reader's experience. Here we explore "Letter Eight, The Sistine Chapel, Rome: Body Language, God-Talk, and the Visible Invisible." Click here to view the entire series.

The art historian Sydney Freedberg once said, “The Sistine Ceiling basically means what it instantly and evidently says.” To enter into the Sistine Chapel is to enter into a claim about the nature of creation and the human person, but this claim isn’t merely philosophical. It is a shimmering, dynamic, and vibrant claim, pulsing with life and color across the walls and over the ceiling of the chapel. The ceiling paintings are a proclamation of the goodness of creation and of the human person and the tragic consequences of the Fall, while the walls argue for the hope of redemption from the consequences of sin. It is a claim that envelopes and surrounds the viewer.

It is a ceiling that almost was not painted. The tempestuous Michelangelo had been commissioned by Pope Julius II in 1506 or 1507, but it was a commission the artist did not want. He fled to Florence hoping to avoid the willful Julius but was ultimately forced to accept in 1508. Pope Julius originally wanted the ceiling to be covered in complex arabesque designs, but Michelangelo convinced Julius to allow him to paint a more complex narrative of creation, sin, and redemption. The result is nine colorful and distinct panels that trace out the first moments of salvation history, from the first instance of the creation of the world and humanity to the fall of Adam and Eve and the drunkenness of Noah. Michelangelo was a sculptor by trade, accustomed to evoking the three-dimensional muscular form and movement of the human body from stone rather than from a two-dimensional surface. This admiration for and familiarity with the human body is manifested beautifully in the parade of pre-Christian sybils, prophets, and nudes that march over the windows and border the central drama of the creation and fall. It is especially evident in the sensitive depiction of the newly created Adam, reaching out to the powerful Creator-Father, and also in the perceptive portrayal of the aged and drunken Noah.

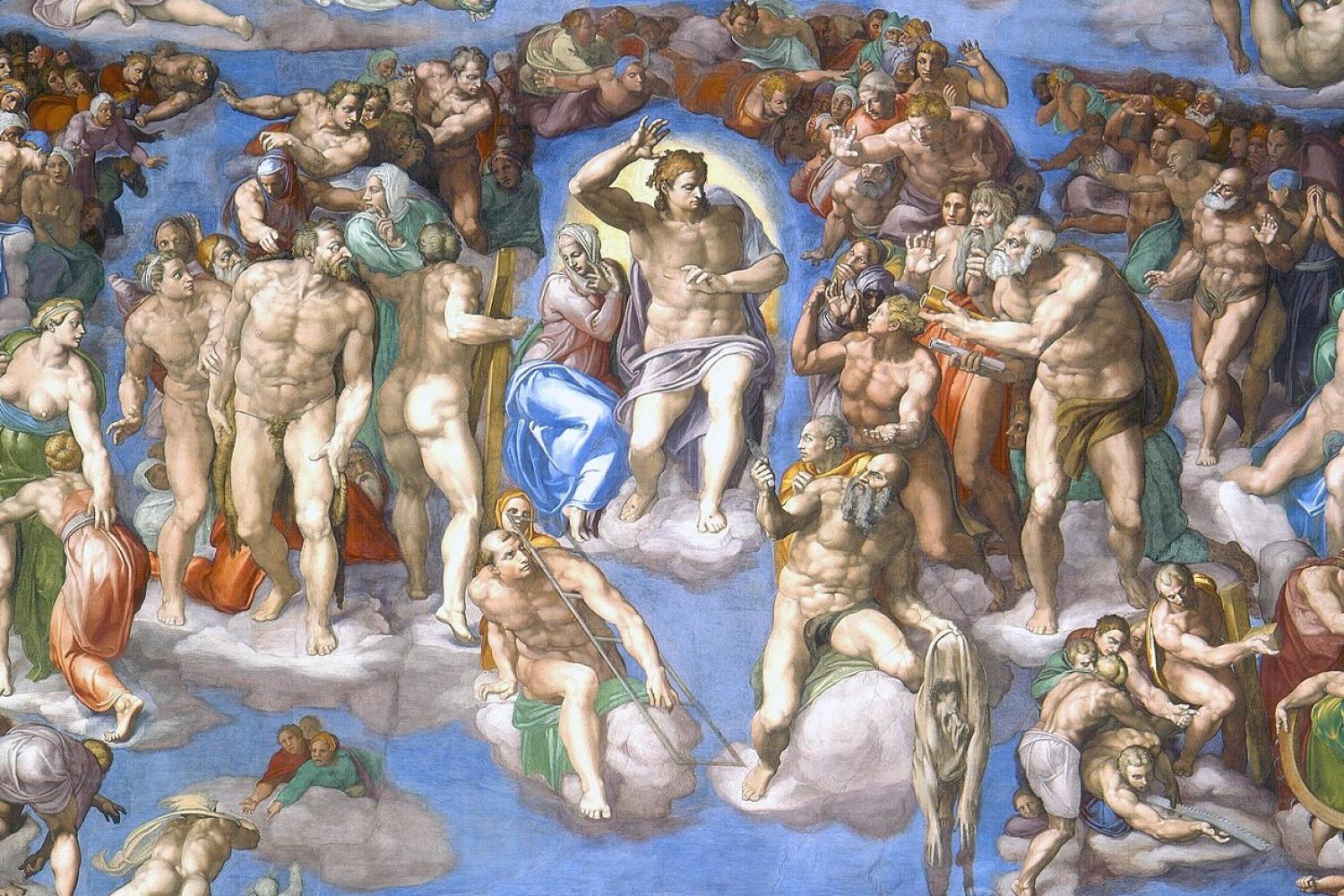

When Michelangelo painted the Sistine Ceiling, he was a young man at the height of his powers, full of life and possibility. Twenty-five years after the completion of the ceiling, he was commissioned again by another pope, the reformer Paul III, to paint the Chapel’s altar wall. What subject should he choose? One side wall depicted scenes from the life of Moses, life under the Law, and the other depicted scenes from the life of Christ, life under grace. Michelangelo was an old man, more reflective and careworn, more aware of mortality. The subject matter the artist ultimately chose is often called The Last Judgment, although some art historians have argued convincingly that it should be called The Resurrection of the Body. In it is displayed the transcendent power and energy of the embodied, resurrected Christ as he ascends into Heaven. Christ’s right hand is raised, palm outward, under which sits his Mother. It is a scene of confrontation: the resurrected Redeemer is surrounded by souls in various states of response to the claims of God. There are the souls who recognize Him as Lord to His right, and the souls who do not to His left, and a swarm of angels and demons fighting for souls beneath Him. This panel is the keystone that holds together the whole artistic plan and theological claim of the Sistine Chapel. Christ, the God-Man, the Savior and Redeemer, long-awaited by Israel as depicted on the Moses wall, the longed-for key to the intractable problem of Adam’s sin and the fulfillment of all creation as depicted on the ceiling, rises in a glorified body and holds out the hope and promise of redemption.

In the eighth chapter of Letters to a Young Catholic, George Weigel uses the artistic and theological claim so energetically rendered in the Sistine Chapel to reflect on John Paul II’s theology of the body, particularly the Law of the Gift: as embodied souls or ensouled bodies, human persons are made purposefully, and that purpose is indicated in our very embodiedness. Male and female bodies are not divine mistakes but are created in such a way as to indicate that they are made for each other. John Paul II argued that before the Fall, man and woman were made as gifts to one another, but that after the Fall, that gift-of-self-to-the-beloved was corrupted by lust, objectification of the other, and self-love. Weigel argues that the great challenge of our age is not self-expression but self-mastery, that channeling of one’s desires and powers as a gift that affirms, ennobles, and seeks the good of the beloved. The human body is a beautiful and powerful thing, as both John Paull II and Michelangelo knew well. This is part of the claim of the Sistine Chapel: created in goodness and for good, the embodied human person finds its purpose and its hope in the Resurrected Christ.

Next: Why and How We Pray

In the ninth chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores restoration and liturgical renewal by focusing on St. Mary's Catholic Church in Greenville, South Carolina.

Previous: Brideshead Revisited and the Ladder of Love

In the seventh chapter of "Letters to a Young Catholic," Weigel explores Castle Howard in Yorkshire, England, to reflect upon the choice offered to us all: submit to reality or fly into fantasy.